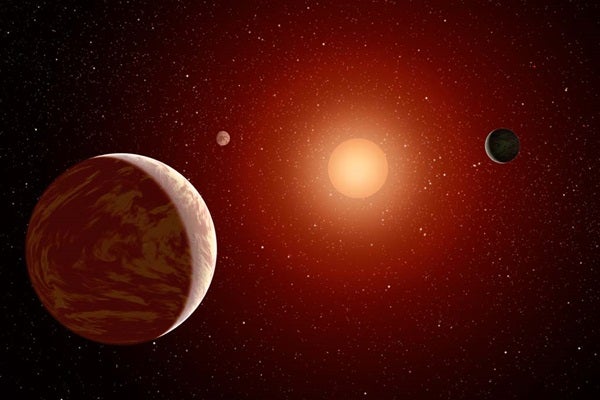

Cool stars have really come into their own lately, especially as discoveries of their planetary systems increase (think TRAPPIST-1 and Proxima Centauri). But despite their relatively cool nature, these stars can put out intense flares that might affect the planets haplessly circling them. The role of such flares remains unknown – but maybe not for long, now that a team of astronomers has begun building a database of dwarf star flares from high-precision data obtained by the Galaxy Evolution Explorer (GALEX) mission.

The database was introduced Tuesday morning at the 230th Meeting of the American Astronomical Society by Chase Million of Million Concepts. Million is the leader of a project called gPhoton, which has undertaken the effort to reprocess data taken by GALEX, which recorded the sky in ultraviolet (UV) light. Thus far, the team has examined more than 100 terabytes of data, looking for flares from red dwarf stars. Although these stars are normally unremarkable in the UV bands, the flares they emit cause them to brighten and become noticeable at these wavelengths, if only for a short time. “The foundation of this work is the observation that the sky changes rapidly,” said Million during the press conference in Austin, Texas.

While large flares are easier to record, smaller flares have also been seen – and they’re predicted to occur more frequently. It’s these smaller flares that Million and his colleagues are looking to identify, thanks to the remarkably high precision (5 thousandths of a second) of the data taken by GALEX. Finding these rapid flares is now possible with the help of gPhoton, which allows astronomers to “unlock that very short time domain data” and “study very fast variables with archival data,” he said.

The gPhoton database is now a trillion photons strong and 1.2 terabytes in size. It’s currently comprised of 10,000 m-dwarf stars with known distances, and each star has its own light curve (a measurement of the amount of light it emits over time). From these light curves, the team has already identified 100 to 200 small flares, each about a minute in length, “at energies that haven’t really been measured before,” said Million.

And these flares could have serious implications for planets around these cool stars. “Habitable planets are closer to cooler stars and cooler stars, we know, have a lot of these flares… Even though small flares are small, because the planets are closer, they will have more of an impact on the habitability of those planets.”

As Scott Fleming of the Space Telescope Science Institute explained in an accompanying press release, “What if planets are constantly bathed by these smaller, but still significant, flares? There could be a cumulative effect.”

Concluding his presentation, Million said, “I’m intentionally vague. This means something – I really do not know. It may be that flares strip away the atmospheres and maybe that they irradiate the surfaces. There’s even a recent preprint where they say … some amount of flare activity may be necessary for prebiotic chemistry. I don’t know, but I’m really excited to get this result out so that other people can tell me what it means.”