Key Takeaways:

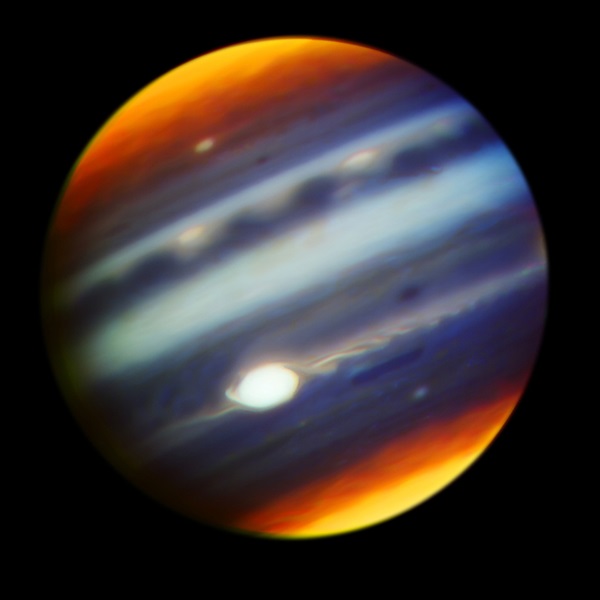

The Gemini North Telescope captured this stunning image of Jupiter in the infrared on May 8, 2017, shortly before Juno completed a close approach of the giant planet.

Gemini Observatory/AURA/NASA/JPL-Caltech

Jupiter’s Great Red Spot is a hurricane-like storm about 10,200 miles (16,500km) wide and at least 150 years old. On July 10, the Juno spacecraft will complete the first ever up-close study of this storm, flying 5,600 miles (9,000km) above the Great Red Spot. In preparation for this landmark opportunity to observe some of our solar system’s most extreme weather, the Gemini and Subaru Telescopes on Mauna Kea have taken some stunning images of Jupiter to supplement the data Juno is expected to obtain.

Why are Earth-based observations so important, when Juno is sitting in orbit around the giant planet? “Observations with Earth’s most powerful telescopes enhance the spacecraft’s planned observations by providing three types of additional context,” Juno science team member Glenn Orton of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory explained in a press release. “We get spatial context from seeing the whole planet. We extend and fill in our temporal context from seeing features over a span of time. And we supplement with wavelengths not available from Juno. The combination of Earth-based and spacecraft observations is a powerful one-two punch in exploring Jupiter.”

The infrared image obtained with the Gemini North Telescope’s Near-InfraRed Imager (NIRI) on May 18 allowed astronomers to probe the uppermost regions of Jupiter’s atmosphere. As one of the highest-altitude features on the planet, the Great Red Spot appears as a bright white oval with narrow streaks on either side. These streaks are thought to be atmospheric features undergoing stretching by the storm’s high winds.

On the same night, the Subaru Telescope imaged Jupiter using its Cooled Mid-Infrared Camera and Spectrometer (COMICS). This data revealed structures further down inside the storm, such as its “cold and cloudy interior increasing toward its center, with a periphery that was warmer and clearer,” said Orton.

This animated gif shows data taken with the mid-infrared imager on the Subaru Telescope in Hawaii on January 14, 2017.

NAOJ/NASA/JPL-Caltech

Juno is scheduled pass over the Great Red Spot at about 7:06pm PDT on July 10. During the flyby, all eight of its instruments, plus its imaging camera, will be actively taking data. Despite the fact that the Great Red Spot has been imaged by spacecraft in the past, July 10’s pass will mark the closest views we’ve seen yet of the storm, which astronomers have been monitoring from Earth since at least 1830.

Among the Red Spot’s many mysteries are its shrinking behavior — since Voyager 1 and 2 measured the storm at 14,500 miles (23,300km) across in 1979, it’s lost several thousand miles in width. Other mysteries associated with the storm include the exact mechanism that produces its red color, which has varied over the years from red to brown.

The Juno spacecraft entered orbit around Jupiter on July 4, 2016. In its first year at the giant planet, it has returned unparalleled views of the planet’s atmosphere, captured the view from inside Jupiter’s rings, and hinted at a planetary core that might be even stranger than scientists expected.