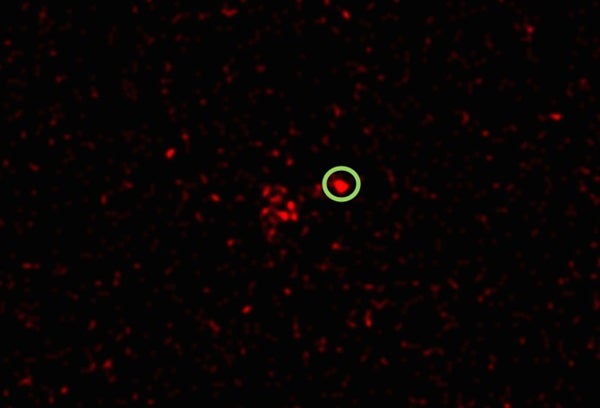

The team discovered the X-ray signature while studying a recent supernova, 2012cav, which was observed with the Chandra X-ray Observatory. In the first observation, taken a year and a half after the supernova went off, Chandra saw 33 X-ray photons coming from the source. Two hundred days later, a second Chandra observation captured 10 photons. Although these numbers are small, they are not insignificant, and have profound implications for the environment around the supernova at the time it exploded. Their work was published online August 23 in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

X-ray emission has not previously been seen from type Ia supernovae, which occur one of two ways: Either a white dwarf (the remnant of a star like our Sun) pulls enough mass off a nearby companion that it explodes, or two white dwarfs in a binary system spiral together and merge, then explode. However, X-rays are often seen from a different type of supernova event, a type II supernova, which occurs when a massive star reaches the end of its life and explodes. In this case, the X-rays occur when the supernova shockwave interacts with an envelope of surrounding material, which the star sheds in the years prior to the end of its life.

Thus, X-ray emission around a type Ia supernova suggests the same thing — there is a cloak or envelope of material around the star, which gives off X-rays when the explosion reaches it. The trouble is, astronomers don’t know why such a cloak of material would exist, because white dwarfs don’t lose mass in the way that massive stars do. And the amount of mass inferred from the X-ray measurements of 2012cav is much too high to have been shed by a normal companion star.

“What we saw suggests a density about a million times higher what we thought was the maximum around Ia’s,” said Vikram Dwarkadas, a professor at the University of Chicago and a coauthor on the study, in a press release.

2012cav is not the only oddball type Ia supernova of this kind. However, it is the first that has been observed emitting X-rays associated with an envelope of gas. “Although other type Ia’s with circumstellar material were thought to have similarly high densities based on their optical spectra, we have never before detected them with X-rays,” said Dwarkadas.

But now that X-rays have been seen coming from one such supernova, astronomers are likely to be awarded time with Chandra to search for the same emission from others. “It is surprising what you can learn from so few photons,” said lead author Chris Bochenek, a graduate student at Caltech. “With only tens of them, we were able to infer that the dense gas around the supernova is likely clumpy or in a disk.”

Now the goal is to determine how the gas got there, and whether such disks are present in other type Ia supernovae as well. In addition to searching for X-rays, astronomers can also look for radio emission to learn more about the environments that foster these important yet still mysterious stellar explosions.