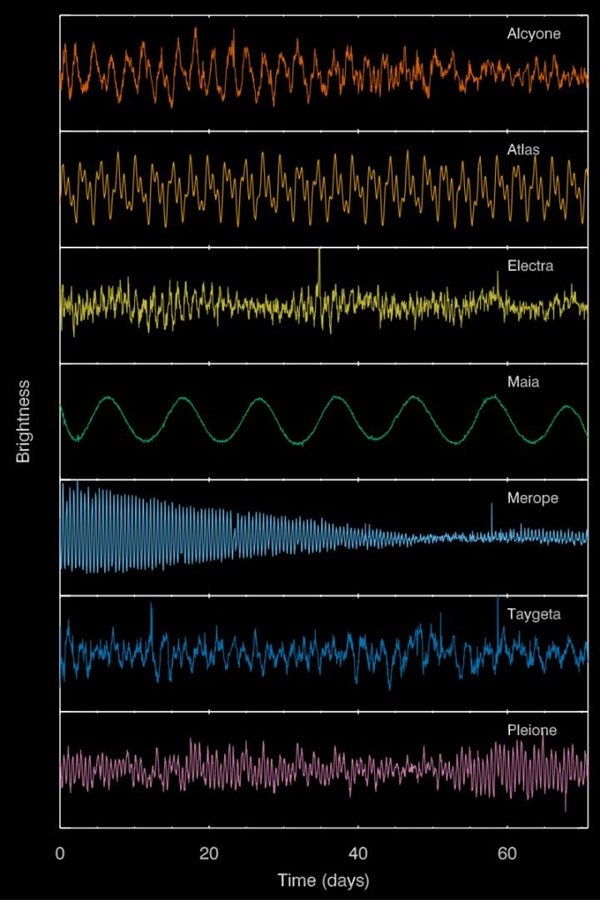

The work was led by Tim White of the Stellar Astrophysics Centre at Aarhus University in Denmark, and published August 11 in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. In their paper, they outline a new technique, called “halo photometry,” which is able to spot relative brightness changes in stars, even if they’re too bright to study directly. The algorithm looks at pixels on the camera detector next to, rather than those that fall directly on, the brightest part of stars. The algorithm measures changes in the values of those pixels to identify variability. As a result, the team discovered that the seven bright stars of the Pleiades are variable stars.

Most of the stars are slowly pulsating B-type stars. These massive, bright stars change brightness every one to five days. Such stars are poorly understood, so adding the stars in the Pleiades to the current list of known variables and studying the Kepler data will help astronomers better understand the processes that affect these stars.

But one star, Maia, was different. Maia exhibits regular changes every 10 days; curious, the team followed up by observing the star with the Hertzsprung SONG Telescope. By looking at spectra, which identify the chemical components of the star, they determined that the brightness changes Kepler saw co-occur with changes in the element manganese in the star’s atmosphere. Rather than pulsating like the other stars do, Maia’s changes appear to be “caused by a large chemical spot on the surface of the star, which comes in and out of view as the star rotates with a ten day period,” said co-author Victoria Antoci, an Assistant Professor at the Stellar Astrophysics Centre, in a press release.

Funny enough, astronomers 60 years ago thought they had detected variability in Maia, but on the order of hours, not days. From those detections a new class of variables, Maia variables, was born — but now, says White, “Our new observations show that Maia is not itself a Maia variable!”

Kepler did not identify any transiting exoplanets during this study; however, the team says their new algorithm will allow Kepler and other planet-hunting telescopes to better search for planets around bright stars, which would have been otherwise skipped because they saturate the detector. They have also released the halo photometry algorithm as free open-source software for the community to use.