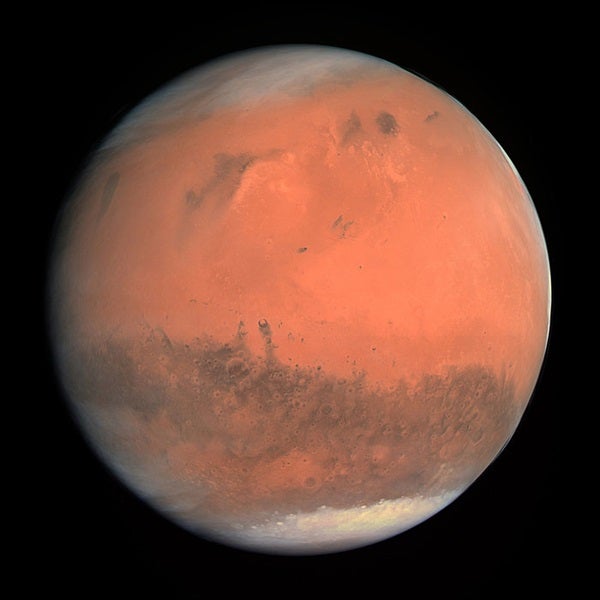

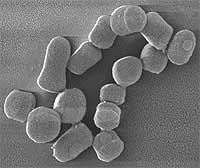

The paper, published today in the journal Extremophiles, focused on naturally occurring microbes in Arctic permafrost sedimentary rocks, one of the best analogues we have to martian regolith here on Earth. The microbes were exposed to Mars-like conditions such as intense gamma radiation (10,000,000 rads [100 kilograys]), extremely low temperatures and pressures (-58 F [-50 C]; 1 Torr [133 Pascals]), and dehydration. The result? A high number of the microbes survived the harsh simulated climate of Mars, raising hopes that microbes on the Red Planet might also survive within the icy regolith well enough for searching rovers or — someday — human scientists to recover them.

The study was conducted using a constant climate chamber and, the authors stress, natural communities of microbes, rather than pure cultures. Studying natural communities allows for a better comparison with reality, allowing for greater biodiversity and increasing the similarities of the studied group to any microbes potentially on Mars.

“In a nutshell, we have conducted a simulation experiment that well covered the conditions of cryoconservation in Martian regolith,” said Vladimir S. Cheptsov, a post-graduate student at the Lomonosov MSU Faculty of Soil Science, Department of Soil Biology, and an author on the paper, in a press release. “The results of the study indicate the possibility of prolonged cryoconservation of viable microorganisms.”

This study is remarkable especially in light of the fact that no previous studies have found living prokaryotes following radiation doses of 8,000,000 rad (80 kGy), lower than the dose used in this study. This is the first time microbes have been shown to survive such high levels of gamma radiation, possibly owing to the biodiversity of the natural sample.

So how about some numbers? “Taking into account the intensity of radiation in the Mars regolith, the data obtained by us makes it possible to assume that hypothetical Mars ecosystems could be conserved in anabiotic state in the surface layer of regolith (protected from UV rays) for at least 1.3-2 million years, at a depth of two meters for no less than 3.3 million years, and at a depth of five meters for at least 20 million years,” Cheptsov said.

That’s a nice, long time for life to survive, dramatically upping the chances that we may someday find what we’re looking for in the icy red soil of Mars.

He further added that the study need not only apply to Mars. As searches for life throughout our solar system, in particular on icy moons, ramp up, these results “can also be applied to assess the possibility of detecting viable microorganisms at other objects of the solar system and within small bodies in outer space,” he said.