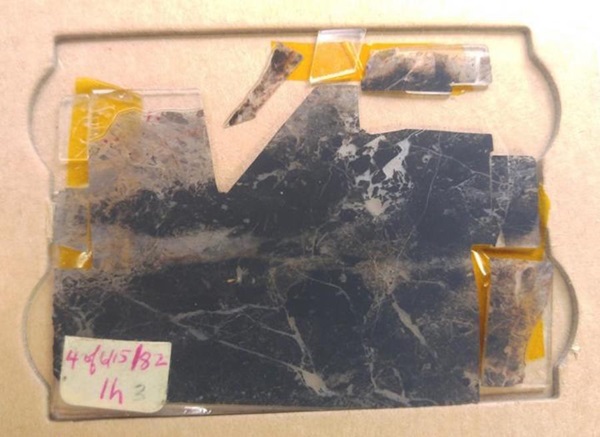

The findings not only suggest that life on our planet originated some 4 billion years ago, but also help support the increasingly widespread theory that life in the universe is much more common than we previously thought.

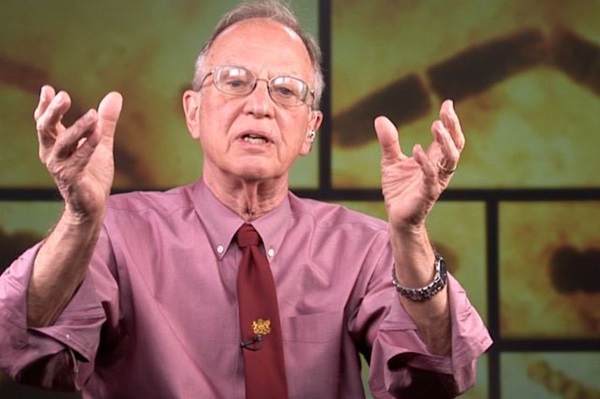

“By 3.465 billion years ago, life was already diverse on Earth; that’s clear,” said J. William Schopf, a professor of paleobiology at UCLA and the study’s lead author, in a press release. “This tells us life had to have begun substantially earlier, and it confirms that it was not difficult for primitive life to form and to evolve into more advanced microorganisms.”

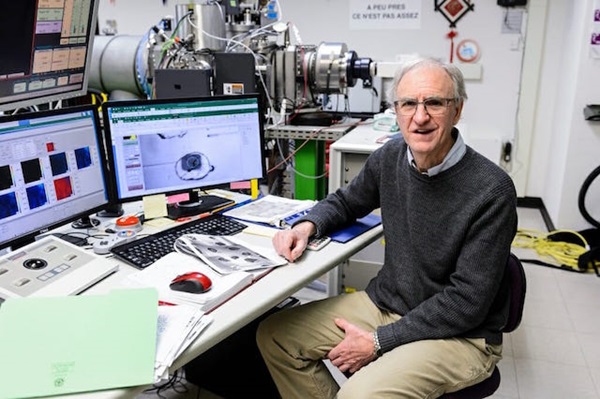

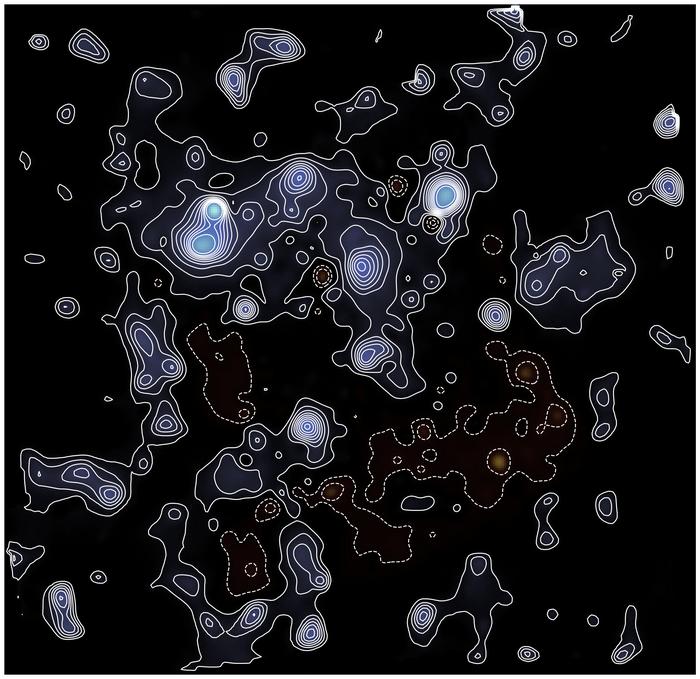

“The difference in carbon isotope ratios correlate with their shapes,” said John Valley, professor of geoscience at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and co-author of the study. “Their C-13-to-C-12 ratios are characteristic of biology and metabolic function.”

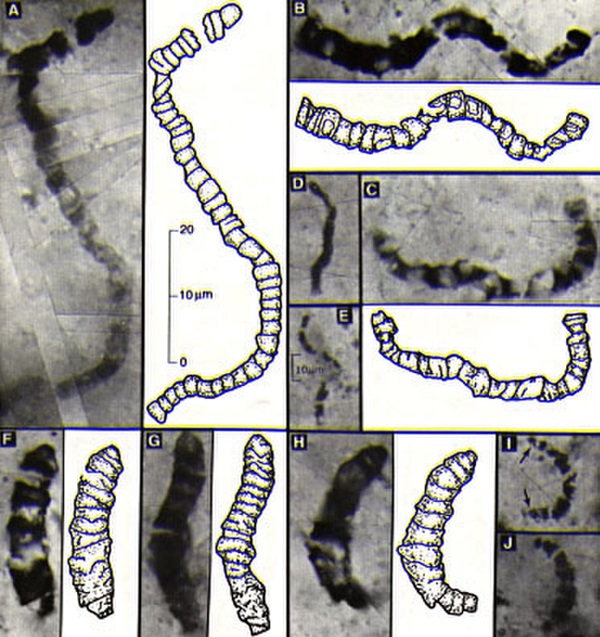

Based on the chemical analysis, the researchers concluded that the 11 fossilized microbes spanned five different taxonomical groups. Some of the microbes were a type of now-extinct bacteria from the domain Archaea, while others were more similar to microbial species still around today. The analysis also suggests that the microbes existed when there was very little oxygen present in Earth’s atmosphere.

Whether or not oxygen was deadly to the microbes, the results show that “these are a primitive but diverse group of organisms,” Schopf said. Their complex and varied structures at such an early point in Earth’s history demonstrate that life can take root and evolve much more rapidly than previously thought.

When combined with the fact that there are trillions of stars in the universe — and the growing consensus among astronomers that exoplanets are commonplace — the case for life existing elsewhere in the universe has never been stronger. “If the conditions are right, it looks like life in the universe should be widespread,” Schopf said.

The most recent findings “will probably touch off a flurry of new research into these rocks as other researchers look for data that either support or disprove this new assertion,” said Alison Olcott Marshall, a geobiologist at the University of Kansas in Lawrence who was not involved in the study, in a press release.

“People are really interested in when life on Earth first emerged,” Valley said in a press release. “This study was 10 times more time-consuming and more difficult than I first imagined, but it came to fruition because of many dedicated people who have been excited about this since day one … I think a lot more microfossil analyses will be made on samples of Earth and possibly from other planetary bodies.”