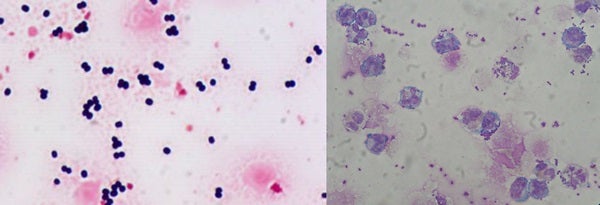

On December 18, NASA released a statement which announced that Whitson is now officially the only person to ever take DNA samples from unknown microbes found aboard the ISS and successfully identify them while in space. The mysterious microbes, which Whitson analyzed as part of the Genes in Space-3 mission, were found to be two relatively common organisms often associated with the human microbiome: Staphylococcus hominis and Staphylococcus capitis.

In order to identify the unknown organisms, Whitson and her fellow astronauts had to first collect the microbial samples by touching petri dishes to the space station’s internal surfaces. Whitson then took these samples and bolstered them using a technique called Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), which amplifies microbial samples by taking a few copies of a particular DNA segment and generating thousands or millions of more copies.

These enhanced samples were then transferred from the petri dishes to small test tubes within the space station’s Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) — another first for microbiological research in space. Finally, using a portable, real-time sequencing device known as MinION, Whitson analyzed the amplified samples before beaming the data back down to Earth.

After collecting the microbe samples from inside the International Space Station, Whitson transferred them from petri dishes to test tubes within the Microgravity Science Glovebox. This is the first time such a task has been performed in space.

NASA

“Once we actually got the data on the ground, we were able to turn it around and start analyzing it,” said Aaron Burton, NASA biochemist and the project’s co-investigator. “You get all these squiggle plots and you have to turn that into As, Gs, Cs, and Ts.”

These four letters — representing Adenine, Guanine, Cytosine, and Thymine, respectively — are the only four bases that make up every strand of DNA for every living organism that we know of. By analyzing how these bases are arranged within a DNA strand, scientists are able to identify which organism the DNA came from.

“Right away, we saw one microorganism pop up, and then a second one, and they were things that we find all the time on the space station,” said NASA microbiologist Sarah Wallace.

“It was a natural collaboration to put these two pieces of technology together because individually, they’re both great, but together they enable extremely powerful molecular biology applications,” said Wallace.

Considering that microbial samples have previously always had to be returned to Earth for analysis and identification, the ability to sequence DNA entirely in space marks a major stepping stone in the future of human spaceflight. According to the NASA statement, “The ability to identify microbes in space could aid in the ability to diagnose and treat astronaut ailments in real time, as well as [assist] in the identification of DNA-based life on other planets.”