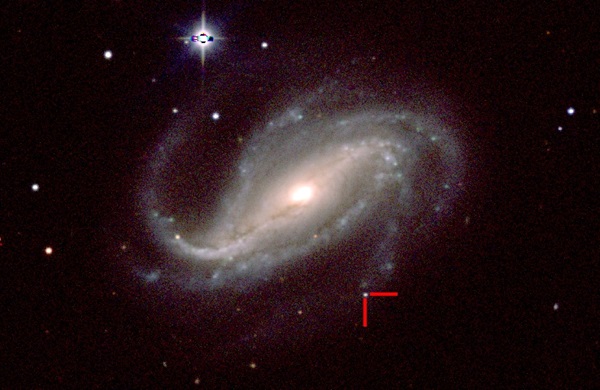

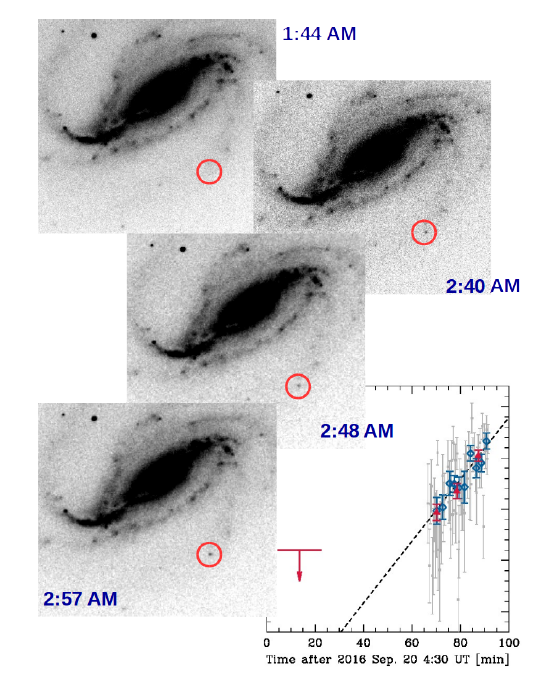

Once the sky was dark, Buso pointed his telescope at NGC 613 — a spiral galaxy located some 70 million light-years away in the constellation Sculptor — to take a series of short-exposure photographs. To ensure his new camera was functioning properly, Buso examined the images right away. This is when he noticed that a previously invisible point of light had appeared on the outskirts of NGC 613, and the point was quickly growing brighter as he moved from one image to the next.

Within no time, astronomer Melina Bersten and her colleagues at the Instituto de Astrofísica de La Plata learned of Buso’s fortunate photo shoot. They immediately realized that Buso had caught an extremely rare event — the initial burst of light from a massive supernova explosion. According to Bersten, the chances of making such a discovery are between 1 in 10 million and 1 in 100 million.

“Professional astronomers have long been searching for such an event,” said UC-Berkeley astronomer Alex Filippenko, whose follow-up observations were critical to analyzing the explosion, in a press release. “Observations of stars in the first moments they begin exploding provide information that cannot be directly obtained in any other way.”

“It’s like winning the cosmic lottery,” he added.

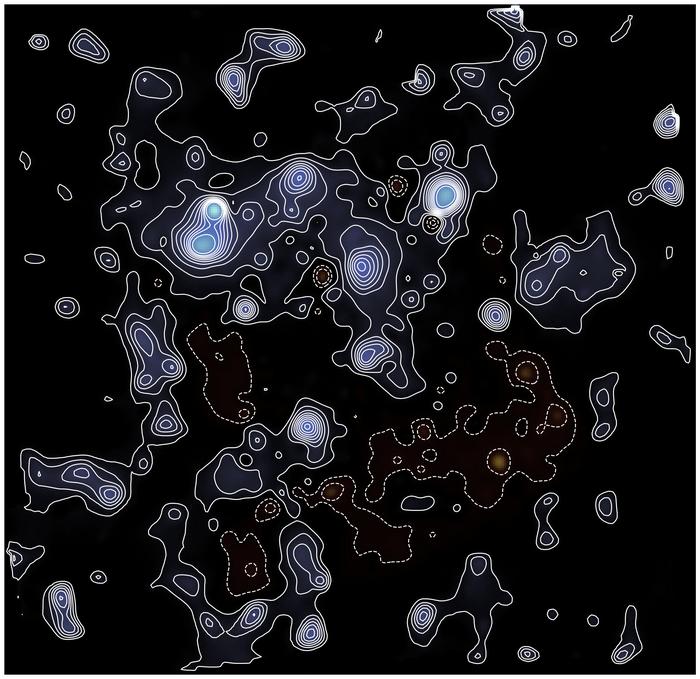

Using the Shane 3-meter telescope at the University of California’s Lick Observatory, as well as the twin 10-meter telescopes of the W. M. Keck Observatory in Maunakea, Hawaii, Filippenko and his colleagues obtained a series of seven spectra. This allowed them to break down the supernova’s light into its constituent components, much like raindrops separate white light into all the colors of the rainbow.

With the spectra, the researchers were able to conclude that SN 2016gkg was a Type IIb supernova, which occurs when a massive star that has lost most of its hydrogen shell explodes.

Furthermore, by comparing the data to theoretical models, the team estimates that the mass of the star before it went supernova was about 20 times the mass of the Sun. However, they point out that the star likely lost around 75 percent of that mass to a companion star prior to the explosion.

Based on all the available data, the researchers believed that Buso captured the first optical images of a supernova undergoing “shock breakout,” which occurs when a supersonic pressure wave from the star’s rebounding core slams into the gas at the star’s surface. This generates a tremendous amount of heat at the star’s surface, which causes a burst of light that rapidly brightens.

The discovery of SN 2016gkg, as well as the results of the follow-up observations, will be published on February 22 in the journal Nature.