At least, usually.

Last November, astronomers made a stunning announcement: They’d found a star that had cheated death. This strange “zombie star” has been observed going supernova twice, once in 1954 and again in 2014. It is the first such object of its kind ever discovered.

The star’s name is iPTF14hls, and its behavior has been called “the biggest puzzle I’ve encountered” by Iair Arcavi, lead author of the discovery paper.

What’s going on here? To dig deeper into the puzzle behind this mysterious star, The Kavli Foundation recently hosted a roundtable discussion with several experts in the field, and generously shared the result with Astronomy magazine, republished below.

IT’S BREAKING ALL THE RULES. Ordinarily, a supernova marks the death of a mammoth star, which then briefly outshines an entire galaxy before fading away. Not so for a baffling supernova that went off in a nearby galaxy in 2014. Instead of being the end of the story, the stellar explosion inexplicably began to brighten and has since dimmed, then brightened up again four more times.

If that weren’t odd enough, it turns out a supernova blew up in the same place in the sky more than 60 years ago. Somehow, a star that apparently died around the time Elvis Presley released his first record endured only to die again—truly a “living dead” star.

Astrophysicists suspect this apparent stellar zombie was a rare, colossal type of star with 50 to 100 times the mass of our Sun. The universe’s first stars were similarly huge, they think, though these distant objects lie beyond the reach of even our most powerful telescopes. The re-exploding star could, therefore, be a cosmic anachronism, offering scientists an unprecedented glimpse into the primeval universe.

To discuss the major scientific potential of this supernova, The Kavli Foundation reached out to two scientists key to its discovery, as well as an astrophysicist who specializes in massive stars.

The participants were:

• IAIR ARCAVI – is an observational astronomer and NASA Einstein Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB) and the Las Cumbres Observatory, as well as a former researcher at the Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics (KITP). He is the lead author of a Nature paper describing the strange supernova.

• LARS BILDSTEN – is the Director of KITP and a Professor in the Physics Department at UCSB. A co-author of the new paper, Bildsten’s specialty is developing theories that explain supernovae.

• EMILY LEVESQUE – is an Assistant Professor of Astronomy at the University of Washington. Her research focuses on massive stars, such as the one implicated in this re-exploding supernova.

The following is an edited transcript of their roundtable discussion. The participants have been provided the opportunity to amend or edit their remarks.

THE KAVLI FOUNDATION: Iair, you’ve called this supernova the biggest puzzle you’ve seen in your career studying stellar explosions. What makes it so puzzling?

IAIR ARCAVI: Most supernovae get bright over a few days or weeks, then fainter over a few weeks and months, and then they disappear and we never see them again. This supernova has gone bright-faint, bright-faint about five times over the course of three years! We’ve never seen that before.

Another weird thing is when we took a spectrum, or fingerprint, of this supernova, which is useful for identifying what type it is, we got very ordinary results. Despite the supernovae’s strange behavior, the spectrum matched that of the most typical supernovae, which have a lot of hydrogen in them. We’ve seen hundreds of those. A normal spectrum was the last thing we were expecting to see.

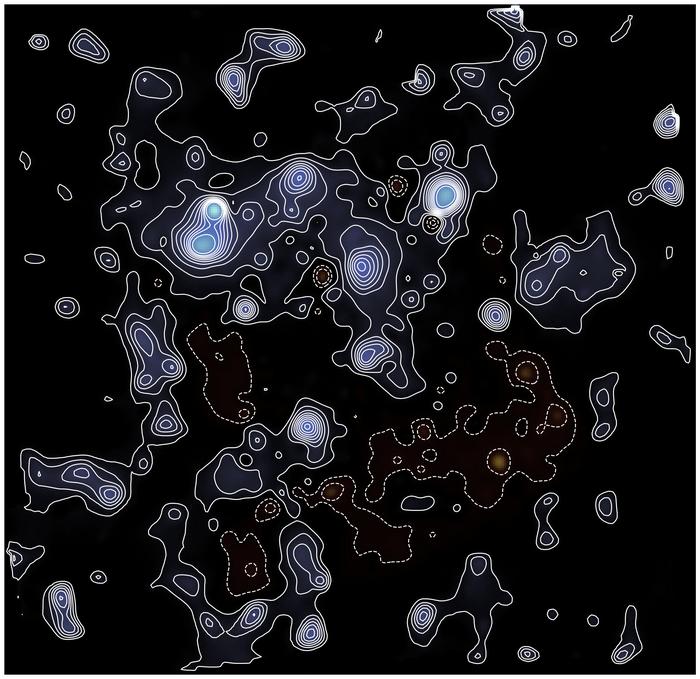

The third puzzling thing: We found this photographic plate from 1954 with an image of this supernova’s host galaxy, and we can see a supernova going off at the same position. We’ve never seen the same place in the sky explode twice before—let alone 60 years apart.

ARCAVI:

It was paper co-author Peter Nugent, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley and at Berkeley Lab, who thought to look back to see if there was any information in the historical surveys. Interestingly, the 1954 image was taken by the same telescope that discovered the supernova in 2014! In 1954, the telescope surveyed the entire sky, and it did so again in 1993. All of the photographic plates from both of those surveys were scanned, digitized, and put online. You can go to a website, type in any position in the sky, and it’ll show you the images from those past surveys. When Peter punched in the coordinates of this unusual supernovae, he discovered in the 1954 survey a bright source of light at that same position. We were all very surprised when we saw that!TKF: Emily and Lars, what were your reactions to the discovery of this supernova?

EMILY LEVESQUE: I learned about it when the paper came out. Students in my research group immediately started pitching around ideas about what this supernova could be. We study massive stars and are really interested in their death throes, their final evolutionary states before they become supernovae. The more we read about this new supernova, the weirder it got.

LARS BILDSTEN: Over the past few years, Iair had shared with me and some colleagues the news about the strange rebrightening of this supernova. We had started trying to do theoretical work to understand it, but the fun part was, none of our ideas were working!

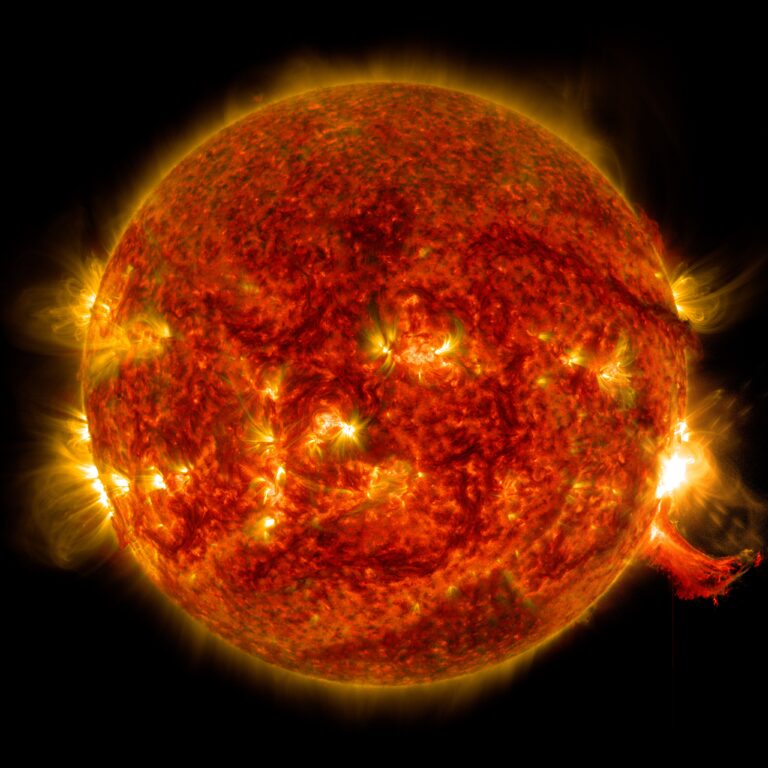

The big question remains, what is the supernova’s source of energy? Typical supernovae, from a collapsing, massive star, are gone after about 100 days. That’s because the explosion leaves only a certain amount of energy in the stellar material that gets blown out into space. The temperature of that material, and the light it gives off, drops over time. But that didn’t happen for this supernova. Its material is getting re-energized, and it’s a pretty open question as to how.

“We’ve never seen the same place in the sky explode twice before — let alone 60 years apart.” — Iair Arcavi

TKF: Well, what could be causing this supernova to behave that way?

BILDSTEN: It could be related to something called “pair instability,” which is a phenomenon we think can happen in the most massive stars in the universe, those that have more than 100 times the mass of our Sun. These stars get so hot that they start making electron-positron pairs. Electrons are the familiar negatively charged particles that swirl around nuclei in every atom, whereas positrons are their positively charged counterpart usually only created when nuclei undergo radioactive decays. However, once the center of the star reaches conditions where the radiation is able to create these pairs, the pressure support in the star declines. That forces a partial collapse, igniting a runaway thermonuclear reaction that triggers an explosion.

Smaller stars can go in and out of producing electron-positron pairs. During one of these episodes, the star falls in on itself somewhat and ejects a large part of its mass. But the star survives, only to then have another contraction and a later ejection. So obviously seeing something that is bright in 1954 and then again in 2014 is suggestive of this mechanism. I would say it’s a good working hypothesis.

LEVESQUE: Understanding how the very first stars in the universe behaved, how they were born, evolved and died, is really the key that we need to explain the chemical evolution of our universe. This goes back to the “we’re all made of star stuff” idea from Carl Sagan. To understand where the first “star stuff” came from, we have to understand the first stars. But they’re simply too far away to observe directly.

Instead, we have to look at stars that are closer and that might behave similarly to those first stars. This unusual supernova might help us understand how the very first, massive stars died. It’s the first, best and so far only example we have.

BILDSTEN: All of us would love to find the ‘first star.’ That’s a frontier we’ll keep probing with the next generation of major telescopes.

TKF: What are we to make of the fact this strange supernova, supposedly unleashed by a kind of star that hasn’t existed since the early universe, happened in a nearby, “modern” galaxy?

ARCAVI: That is another very perplexing thing about this supernova. Why is it in a galaxy only about 500 million instead of billions of light-years away? There are some intriguing clues.

It is in a very faint, small galaxy, the kind that is typically poor in what we astronomers call “metals,” which are chemical elements heavier than helium. Being metal-poor actually helps stars grow more massive. Also, this supernova happened at the edge of this galaxy, where we expect the supply of metals to be at its lowest. These kinds of regions might be a lot like what the entire universe was like at earlier times, shortly after the Big Bang, when massive stars should have formed.

LEVESQUE: That’s right. There could be entire galaxies, or little pockets within galaxies, that have a chemistry similar to the young universe. In fact, we know of fairly nearby galaxies, like I Zwicky 18, that are extremely low in metals. As we get more powerful telescopes in the years ahead, we’re going to get better at mapping the metal content in galaxies. We want to see if supernovae tend to explode in metal-poor or metal-rich environments.

“All of us would love to find the ‘first star.’ That’s a frontier we’ll keep probing.” — Lars Bildsten

ARCAVI:

That’s a very important aspect of this discovery. These observations would’ve been almost impossible to do just a few years ago, and that might be another reason we haven’t seen this kind of supernova before.The Palomar Transient Factory was a revolutionary new survey that detected flashes of light in the sky. It discovered about 10 new supernovae a night—too many to follow. So we did triage every night to pick out the interesting ones. It was kind of by luck that the Palomar Transient Factory just kept monitoring this seemingly ordinary supernova for us, because then we saw it getting brighter again and realized something interesting was happening.

At that point, we triggered the Las Cumbres Observatory, which is a robotic network of telescopes. From that point, for about three years, we were able to take images and fingerprints of the supernova every three days. That would’ve been very hard before. With a regular telescope, you have to travel to the observatory, manually input your observations, then travel back, then analyze your data, and if you’re lucky, you might get another night at the observatory a month later. Obtaining the data that Las Cumbres got us would’ve required a full-time graduate student and a ton of dedicated telescope time.

Instead, we just clicked a button and the telescope network automatically went to work. I clicked that button three years ago and I didn’t tell it to stop, so we just kept getting data for three years. Having that continuous coverage really lets us confront the theoretical models which try to explain this supernova.

These robotic facilities have definitely played an important role in finding things that are very rare and following them continuously and intensively. That’s only going to get stronger, with the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope next decade, along with other robotic telescopes coming online. They are changing the way we do observations.

LEVESQUE: The Large Synoptic Survey Telescope is going to be ideal for finding more of these sorts of supernovae. It’s going to survey most of the southern sky every few nights, looking for anything that’s gotten brighter or dimmer or moved. By default, it’ll get amazing data on objects like this supernova and on lots of other strange things. The challenge actually becomes this immense computational problem of sifting through all the strange things that have changed to pull out what we want to look at.

“There could be entire galaxies, or little pockets in galaxies, that have a chemistry similar to the young universe.” — Emily Levesque

TKF: Iair, the science press nicknamed the star behind this repeating supernova a “zombie” star, which we have likewise described as a “living dead” star. What do you think of the metaphor?

ARCAVI: Well, I’m not a fan actually, because the zombie star metaphor has been used at least four or five times in the past for different phenomena. But I’ve heard the suggestion—and I like this idea better—to call it the “phoenix star,” which rises from the dead to continue shining. I’m not taking any bets on whether the star is now completely dead or not. It might still be there and could surprise us again. Clearly, it has surprised us before.

TKF: If the star keeps coming back, maybe we could call it a “cat” star, because it has nine lives.

LEVESQUE: I’m wondering if a more apt name would be something like an “opera” star, because it’s like the lead singers in an opera who get killed in a sword fight and keep singing for 10 minutes before they die!

— Adam Hadhazy, Winter 2018

The content of this roundtable is available courtesy of The Kavli Foundation.