“It’s remarkable that we’ve now seen, for the first time, a physical object from outside our solar system,” said Alan Jackson, a postdoc at the Centre for Planetary Sciences at the University of Toronto Scarborough and lead author of a new study on ‘Oumuamua, in a press release.

Though the discovery of ‘Oumuamua was not entirely unexpected (planetary scientist Alan Stern, for one, predicted the eventual discovery of an interstellar object in the February 1997 issue of Astronomy), it still caught astronomers a bit off guard. But since the detection of ‘Oumuamua, countless scientists from around the world have collected data on the mysterious object in hopes of filling in the details of its origin story.

In a new study published March 19 in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Letters, a team of astronomers added one more piece to the puzzle. They found that ‘Oumuamua’s original host star was not just one star at all, but instead a pair of stars orbiting a common center of mass. ‘Oumuamua likely came to our solar system from a binary star system.

To carry out the study, Jackson and his team created models to test how efficient different star systems are at ejecting asteroids and comets. Using these models, they showed that rocky objects like ‘Oumuamua are much more likely to be ejected from binary star systems rather than from single star systems.

Though this result is interesting in and of itself, it also helps solve a nagging question that has perplexed astronomers since ‘Oumuamua’s discovery: Why is it an asteroid and not a comet?

“It’s really odd that the first object we would see from outside our system would be an asteroid, because a comet would be a lot easier to spot and the solar system ejects many more comets than asteroids,” said Jackson.

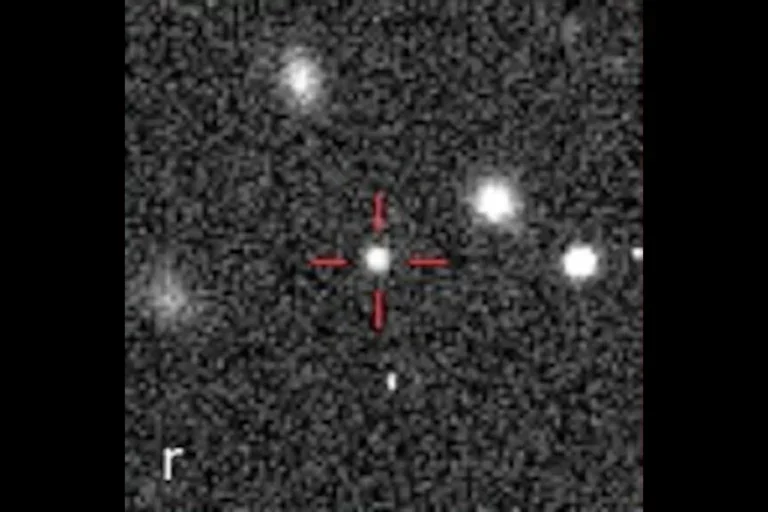

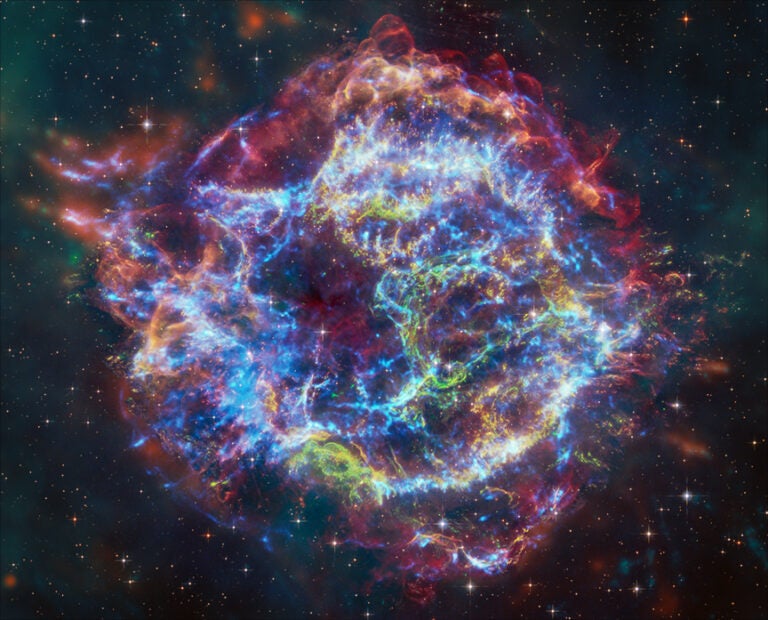

In October 2017, the modest WIYN Telescope at Kitt Peak captured this series of images tracking ‘Oumuamua across the sky. Though the asteroid passed relatively close by Earth, it was about 10 million times fainter than the faintest star visible with the naked eye.

R. Kotulla (University of Wisconsin)/WIYN/NOAO/AURA/NSF

Astronomers previously thought that the majority of interstellar objects ejected from star systems should be comets. This is because comets form much farther away from their host stars than asteroids do, so comets are less tightly bound and more susceptible to being ejected. Instead, the new study suggests that asteroidal objects like ‘Oumuamua should be about as common as interstellar comets.

According to the study, “Whereas in the solar system the ejected material is overwhelmingly icy [comets], we expect that around 36% of binaries may predominantly eject material that is rocky or substantially devolatilized, leading to similar expectations for the abundance of rocky/devolatilized bodies in the interstellar population.” Even though only about one-third of binary systems eject primarily asteroids, since binary systems make up the majority of star systems, Jackson and his team determined the overall number of interstellar asteroids should be about equal to the number of interstellar comets.

Although the new findings do not shed light on which specific star system ‘Oumuamua came from, the results do give astronomers a baseline for what types of cosmic tourists they should expect to spot in the future. Furthermore, by understanding how these objects came to be, researchers can learn a great deal about the formation and evolution of their host systems.

“The same way we use comets to better understand planet formation in our own solar system, maybe this curious object can tell us more about how planets form in other systems,” said Jackson.