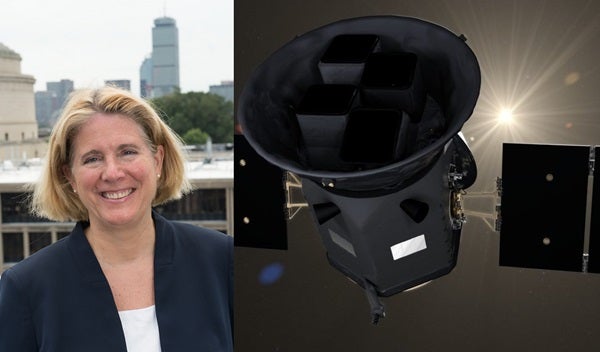

Nurturing TESS from an idea to the drawing board, and then from the fabrication lab into the final frontier has churned up a whirlwind of activity at MKI for a decade. The director of MKI, Jacqueline Hewitt, has been there for all of it. She pushed to get TESS approved by NASA, oversaw its instrument development, and will also oversee its science operations over the next two years in the hunt for Earth-like planets that could conceivably host alien life.

For a perspective on the impact TESS has already had and will have on MKI, The Kavli Foundation spoke with Hewitt shortly after TESS’ launched on April 18, 2018. In this candid conversation, Hewitt describes the successes and challenges in making TESS a reality, as well as the excitement she and her colleagues feel serving in the vanguard of advancing our understanding of the broader universe.

The following is an edited transcript of the discussion. The participant has been provided the opportunity to amend or edit her remarks.

JACQUELINE HEWITT: It was 12 years ago and the field of exoplanets was still in its relative infancy. We did not know yet if exoplanets were these rare things or quite common in the galaxy. Astronomers were talking about the measurements we needed in order to find more planets and to study them. It’s a really difficult problem because exoplanets are, of course, so far away and so tiny and faint from a cosmic perspective.

Back then, George Ricker, a Senior Research Scientist here at MIT and MKI, had finished up his work on the satellite HETE-2. This mission looked for sudden brightening events out in the universe, called transients, caused by the explosions of stars and other phenomena. TESS grew out of HETE-2. George and his colleagues had the realization that going to space would give them the ability to accurately gather enough light to find exoplanets when they cross their host stars, causing just a slight dimming, and also to be able to scan a big portion of the sky to find lots of these planets.

So, I remember George walked into my office and said he had this idea for this mission. In your job as director of a place like MKI, you have to figure out how to put scarce resources into different things. A lot of people will walk into my office with ideas, and to be honest, oftentimes they’re not very good ideas. But this idea for TESS, as soon as I heard it, I thought: “Wow—this is timely, the technology is up to it, this is something we’d be able to do now.” I went into high gear at that point, trying to raise money and develop a consensus within our astronomical community that TESS would be a good thing to do.

George had to do some technology development to make this work, to get it funded. NASA tends to avoid risk in these space missions because they’re so expensive. If you’re going to spend millions sending something in orbit, you want it to work, you know? We put quite a bit of money and time into developing a prototype camera. The whole time, George has really been the champion of TESS. He’s someone who has a real talent for designing instruments to meet a particular scientific problem.

All the hard work paid off and NASA greenlit the mission, with George serving as the TESS Principal Investigator.

I feel very lucky being here at MIT because we’re able to gather together the resources needed, in terms of funding and intellectual people power. The Kavli Foundation played a big and direct role, too. TESS development began shortly after we’d received our Kavli endowment, so that helped us be in a position to have resources that we could spend on things like TESS. Also, during a period when significant funding was critically needed to support research staff, the Foundation encouraged us to redirect some funds toward TESS, making sure the program stayed strong and kept moving forward.

So, all these things have had to come together. It’s been incredible. And sort of crazy at times. [Laughter]

To Seek Out New Life: How the TESS Mission Will Accelerate the Hunt for Livable Alien Worlds

To Seek Out New Life: How the TESS Mission Will Accelerate the Hunt for Livable Alien WorldsThe just-launched Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) could soon provide the breakthrough identification of dozens of potentially habitable exoplanets right in our cosmic backyard. Two TESS scientists — Greg Berthiaume and Diana Dragomir — provide an inside look at the mission’s development and revolutionary science.

Read the Kavli Spotlight

HEWITT: I’d say in the next five years, exoplanets are definitely going to be a big part of our portfolio. Since we started doing TESS, I’ve had a number of people say to me, “Oh, MIT is the best place to be for exoplanets now.” Which we certainly weren’t 12 years ago! I’m not even sure that’s true now—there are a lot of really good places—but at least we’re in the running. We have new faculty and a lot of postdocs have shown up over the last couple of years because of TESS.

TKF: How else has MKI evolved as a result of pursuing the TESS mission?

HEWITT: I told you about our evolution scientifically, but another way we’ve evolved is in engineering and project management. One thing that’s very hard for a university to do is to maintain the staff needed to do space missions, or even ground-based instruments, because you need mechanical engineers and other specialized staff long term. You need to keep these people employed in between missions so you don’t have to go through the process of staffing up again. Fortunately, TESS was a nice, long sustained mission to develop. We were able to maintain some staff and they’ve been working on other projects as well as TESS. So that’s strengthened our capability moving forward.

The TESS mission also deepened the ties between MKI and MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory, which is a federally funded research and development center that built TESS’ cameras. The engineers at Lincoln have been developing the detectors for x-ray missions for us for decades. But TESS certainly was the biggest thing we’ve ever done with Lincoln. We’ve really built a relationship between our people and those out at Lincoln, about 20 miles away, where they maintain a very deep expertise in engineering that we just cannot.

“…[I]t’s always a little scary for any spacecraft come launch time. You spend 12 years working on this remarkable machine, and then we put it on top of a column of rocket fuel. I mean, how crazy is that?” — Jacqueline Hewitt

TKF: I understand the TESS mission has physically changed MKI’s office space, too. Isn’t there now a science operations center in your building on MIT’s campus in Cambridge, Massachusetts?

HEWITT: That’s right. We’ll actually be running the science payload—those cameras and related equipment—on TESS, and that’ll be really cool. We’ll be doing that from a sort of a war room, where we have a bunch of computer screens on the wall. We’ll be getting the data from NASA’s Deep Space Network of radio dishes worldwide, and we’ll be sending out the commands for TESS’ observing sequence.

Now, we’re not actually running the TESS spacecraft itself, mind you; a company called Orbital ATK is doing that. They won’t let us touch the spacecraft. They don’t want a bunch of astronomers running the spacecraft! [Laughter]

TKF: With a major mission like TESS under its belt, do you foresee MIT and MKI making additional forays into primary mission development and operation?

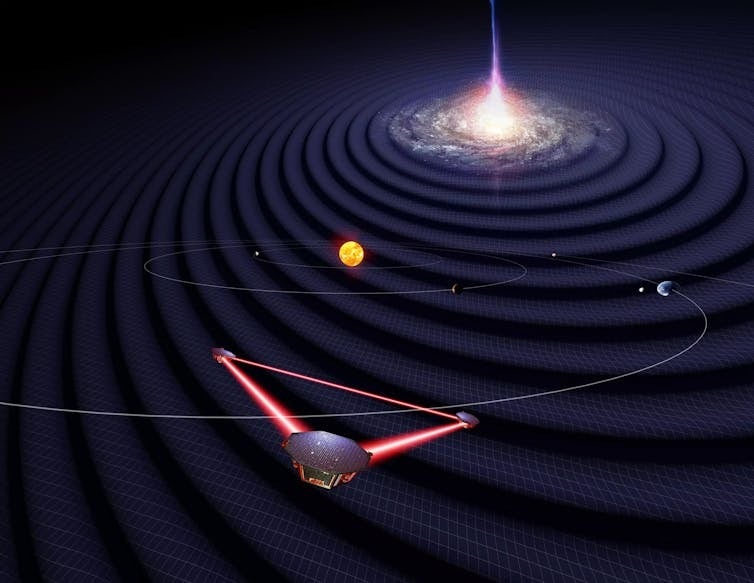

HEWITT: We are having discussions about that. We are presently doing development studies on two other instruments that see the universe in x-rays. One is called Arcus, which will let us study hot gas throughout the universe that we haven’t really been able to see before. The other mission concept is called ISS-TAO, for Transient Astrophysics Observer on the International Space Station, and it will capture transients, such as gamma-ray bursts, and help us better understand them. Those transients include follow-up of the gravitational-wave events detected by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, or LIGO, which is co-led by MIT; and one its founders Rai Weiss, is an MKI member and a Kavli Prize in Astrophysics– and Nobel Prize in Physics-winner. We have some ideas, too, about putting radio arrays in space or on the moon, and that’s something very challenging that I feel more confident about even trying to do now that we have the TESS experience behind us. We kind of have a feeling for what’s involved.

TKF: TESS is the first NASA mission sent to space aboard a rocket from the commercial company SpaceX, which offers less costly rides off-Earth than legacy rockets. What is the significance of this milestone?

HEWITT: I’m a big fan of SpaceX. I still set my alarm for three o’clock in the morning when they have a launch and I watch it on TV and then go back to bed. [Laughter]

It was just so exciting that TESS got launched in this way, but it’s always a little scary for any spacecraft come launch time. You spend 12 years working on this remarkable machine, and then we put it on top of a column of rocket fuel. I mean, how crazy is that? [Laughter]

This milestone really could be a gamechanger in the science we can do. With it not being so monstrously expensive to put something into space anymore, that might get us to start doing missions that are a little bit riskier and bleeding-edge in terms of technology, but which could potentially have big science rewards.

— Adam Hadhazy, Spring 2018

Astronomy.com thanks to The Kavli Foundation for allowing us to repost this content, which originally appeared on kavlifoundation.org.