The evidence, published September 24 in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, comes from Mars Global Surveyor Thermal Emission Spectrometer (MGS‐TES) observations made in the mid-infrared (heat) portion of the spectrum, taken in 1998 as the spacecraft passed the tiny moon on its way into orbit around the planet. While Phobos’ spectrum — the light it reflects, spread out by wavelength to reveal features such as its composition — looks much like that of a D-class asteroid in visible and even near-infrared light, in mid-infrared light (slightly longer wavelengths still), it does not look like an asteroid. Instead, its compositional signature shows basalt, a rock believed to make up the majority of the crust of Mars.

Where’s the match?

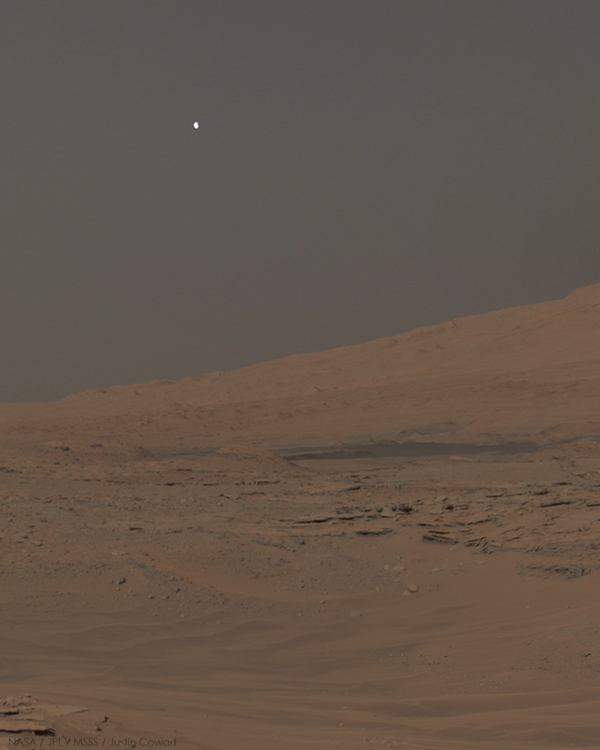

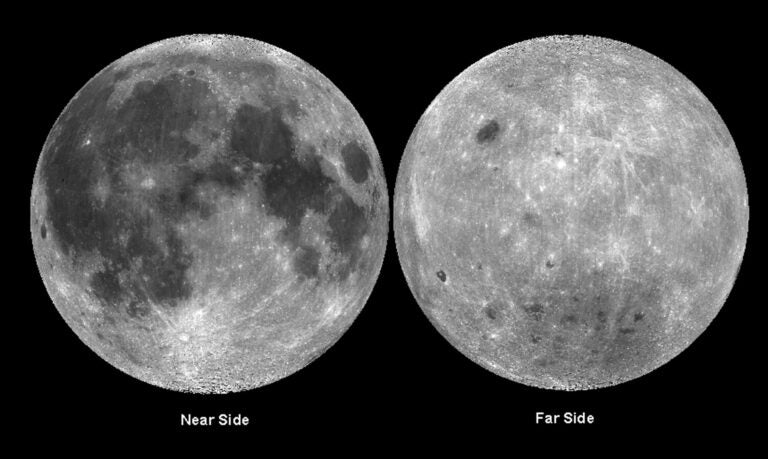

Compared with the planet itself, Mars’ moons appear dark in visible light. This mismatch originally led planetary scientists to believe the moons had been captured by the planet’s gravity sometime in the past. (Unlike Earth’s Moon, which is too large in comparsion with the planet to have been captured, Mars’ moons are tiny compared with the planet itself.) But researchers who study orbital dynamics and have traced back Phobos’ motion over time say that the characteristics of its orbit preclude that possibility.

Now, to solve the mystery of the moon’s origin, scientists have turned to spectral analysis, which allows them to identify whether the moon’s composition more closely matches the planet’s or an asteroid’s. Visible-light observations say Phobos contains carbon, like an asteroid. But what about longer wavelengths?

To determine Phobos’ characteristics in the mid-infrared, Tim Glotch of Stony Brook University in New York and the lead author of the new study compared the MGS-TES observations to mid-infrared observations of the Tagish Lake meteorite, as well as other rock samples. The Tagish Lake meteorite is arguably the best-preserved meteorite sample in the world, and astronomers believe it is a piece of a D-class asteroid — one of Phobos’ possible origins. To ensure a more accurate comparison, Glotch’s team subjected their samples to conditions similar to those that the moon experiences, including exposure to both cold and heat in a vacuum.

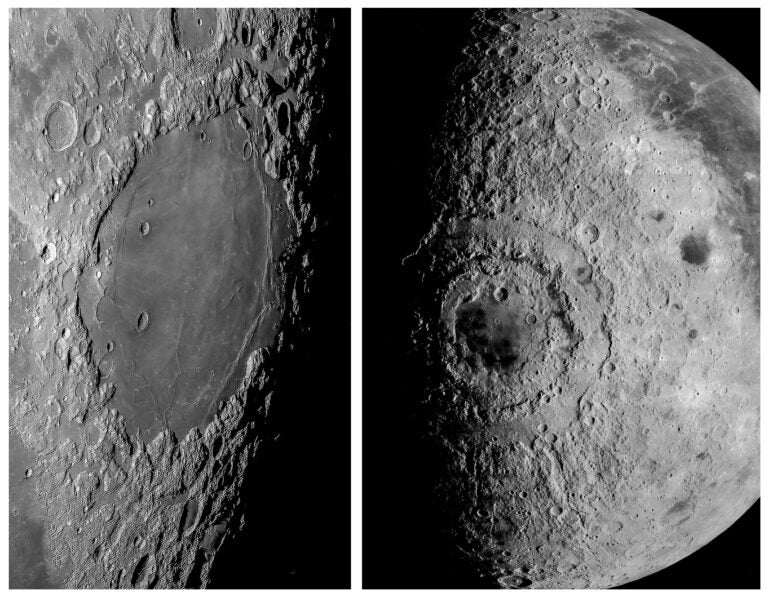

“We found, at these wavelength ranges, the Tagish Lake meteorite doesn’t look anything like Phobos, and in fact what matches Phobos most closely, or at least one of the features in the spectrum, is ground-up basalt, which is a common volcanic rock, and it’s what most of the Martian crust is made out of,” Glotch said in a press release. “That leads us to believe that perhaps Phobos might be a remnant of an impact that occurred early on in Martian history.”

But there are still some caveats. The Tagish Lake meteorite likely came from a D-class asteroid, but it does have some unusual characteristics and may not provide the best example of this type of object for comparison. Additionally, Phobos has undergone space weathering over time, making its spectrum even more complicated and more difficult to exactly match to purer, less-weathered samples in a lab, even given the pains Glotch’s team took.

“The issue of the origins of Phobos and Deimos is a fun sort of mystery, because we have two competing hypotheses that cannot both be true,” said Marc Fries, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Johnson Space Center who was not involved in the study. “I would not consider this to be a final solution to the mystery of the moons’ origin, but it will help keep the discussion moving forward.”

But the answer may not be elusive much longer. We now live in an era where space missions can sample bodies, such as asteroids — Hayabusa2 and OSIRIS-REx — and bring those samples back to Earth for further study. And the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency is currently developing the Martian Moons eXploration mission, for launch in the mid-2020s, which will travel to a martian moon and return a sample to Earth. With such a sample, scientists might finally settle the debate on where Mars’ moons came from — and open the door to better understanding how moons form and are captured in our solar system, and countless others.