Key Takeaways:

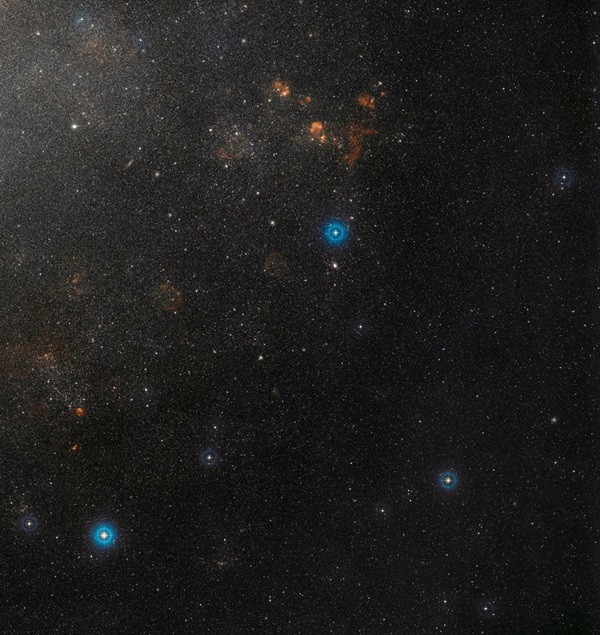

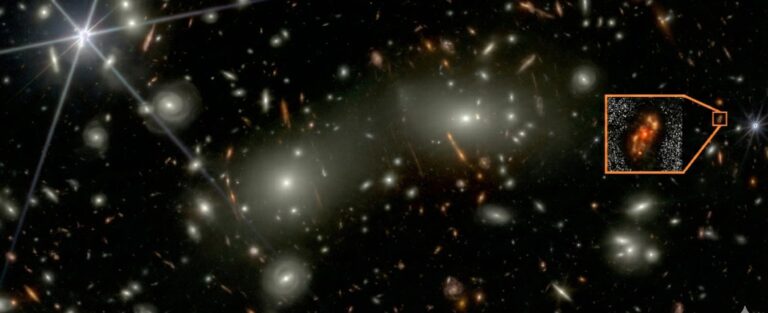

In a new study published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, a trio of astronomers set out to find hypervelocity stars fleeing our galaxy, but surprisingly discovered most of the rapidly moving stars are actually barreling into the Milky Way from galaxies beyond.

“Rather than flying away from the [Milky Way’s] Galactic Center, most of the high velocity stars we spotted seem to be racing toward it,” said lead author Tommaso Marchetti, a PhD candidate at Leiden Observatory, in a press release. “These could be stars from another galaxy, zooming right through the Milky Way.”

Gaia does it again

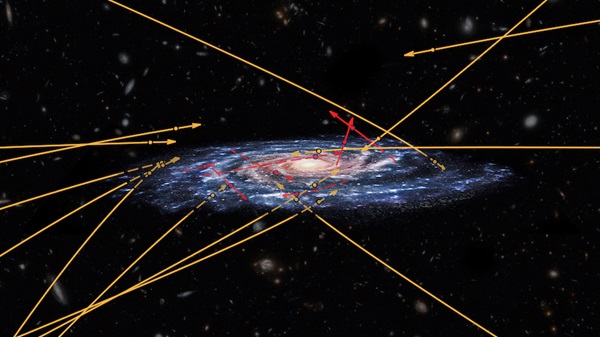

In order to carry out the study, the team — like so many others — relied on data collected by the European Space Agency’s Gaia satellite. In April of this year, Gaia published its much-anticipated second data release, which measured the precise positions, parallaxes, and 2D motions (up-down, left-right) of over 1.3 billion stars in the Milky Way.

For 7 million of the brightest stars in the set, Gaia managed to obtain 3D motions by also measuring how quickly the stars were moving toward or away from the Earth. These stars with accurate 3D motions are the ones that authors of the new study wanted to investigate further.

In particularly, the researchers were hoping to find, at most, one hypervelocity star fleeing our galaxy out of the 7 million they compiled; however, they were pleasantly surprised to find more than just one. “Of the 7 million Gaia stars with full 3D velocity measurements, we found 20 that could be traveling fast enough to eventually escape from the Milky Way,” explains co-author Elena Maria Rossi.

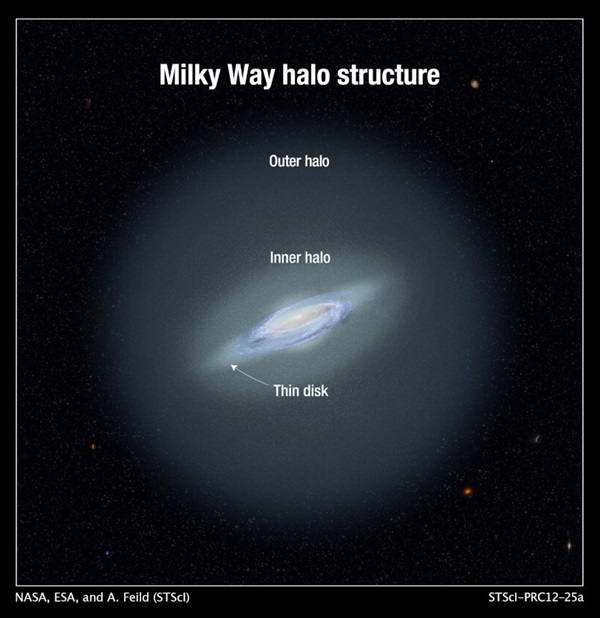

Out of the 20 excessively speeding stars they found, the researchers pinpointed seven so-called “hyper-runaway star candidates,” which are escaping stars that seem to originate from the Milky Way’s galactic disk. Meanwhile, none of stars appear to come from the Milky Way’s core, and the remaining 13 unbound stars (including the two fastest, which zip through our galaxy at about 1.5 million miles per hour) cannot be traced back to the Milky Way at all.

According to the study, if the results are confirmed, these 13 curious stars could very well be the “tip of the iceberg” for a large extragalactic population of stars whizzing through the Milky Way.

Where did they come from?

There are a few possible explanations for how these intergalactic interlopers made their way to the Milky Way. The first possibility is that the hypervelocity stars were ejected from a neighboring galaxy, such as the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC).

According to Rossi, “Stars can be accelerated to high velocities when they interact with a supermassive black hole.” In some cases, they can even gain enough speed to escape their host galaxy altogether. And although astronomers have not yet discovered a supermassive black hole hiding in the LMC, they also have not ruled it out. “So,” Rossi added, “the presence of these stars might be a sign of such black holes in nearby galaxies.”

But even without a supermassive black hole, it’s still possible for another galaxy to eject some of its stars. For instance, “the stars may also have once been part of a binary system, flung toward the Milky Way when their companion star exploded as a supernova,” said Rossi. “Either way, studying them could tell us more about these kinds of processes in nearby galaxies.”

On the other hand, there’s also the possibility that none of the stars are truly from another galaxy at all, and instead just seem to be. However, this alternative still requires an extragalactic push.

Verifying extragalactic origins

To test which origin story is most likely to be true, follow-up studies will need to determine how old the hypervelocity stars really are, as well as determine exactly what they’re made of.

Fortunately, Gaia is expected to release at least two more datasets in the 2020s. And according to co-author and chair of Gaia Data Processing, Anthony Brown, the planned releases will increase Gaia’s total number of stellar 3D velocity measurements from 7 million to 150 million. “This will help [researchers] find hundreds or thousands of hypervelocity stars, understand their origin in much more detail, and use them to investigate the Galactic Center environment, as well as the history of our galaxy,” he said.

So stay tuned, because soon we may know for sure whether stars travel all the way from other galaxies to party in the Milky Way.