Astronomers say they may have found the first confirmed exomoon, or moon orbiting a planet outside of our solar system. However, the pair of astronomers behind the find say it’s much too soon to completely prove the exomoon’s presence.

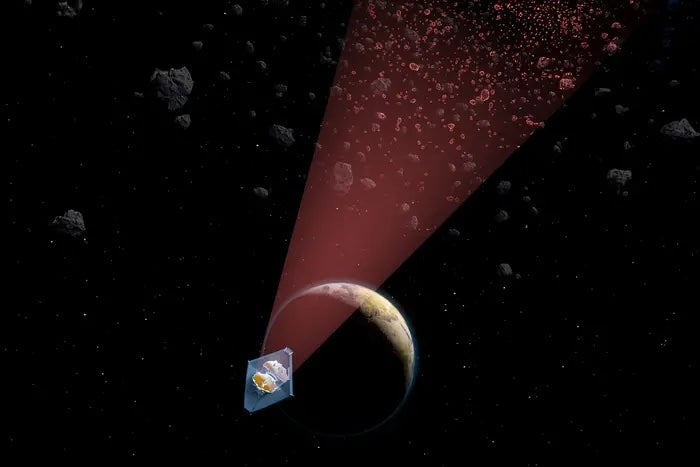

After looking through recent data from NASA’s Kepler space telescope, Alex Teachey, a graduate researcher in the department of astronomy at Columbia University, and David M. Kipping, an assistant professor in the same department, spotted evidence that an exomoon might orbit the Jupiter-sized exoplanet Kepler-1625b.

Transiting planets are worlds that can be detected by a drop in light as they pass in front of their home stars. An when Kepler observed each of 284 transiting planets, the telescope showed a short dimming. The researchers requested and were awarded 40 hours of time to observe these planets’ transits using the Hubble Space Telescope, which is about four times more precise than Kepler.

The researchers hoped to see two short dimming moments that might signal the presence of an exomoon around one of these transiting planets. They also helped to use Hubble to see any gravitational effects that a moon would have on the exoplanet, like changing its transit start time.

About three and a half hours after Hubble observed Kepler-1625b finish transiting, the telescope saw a second short dimming. The two signals together looked like a moon “trailing the planet like a dog following its owner on a leash,” Kipping said in a statement.

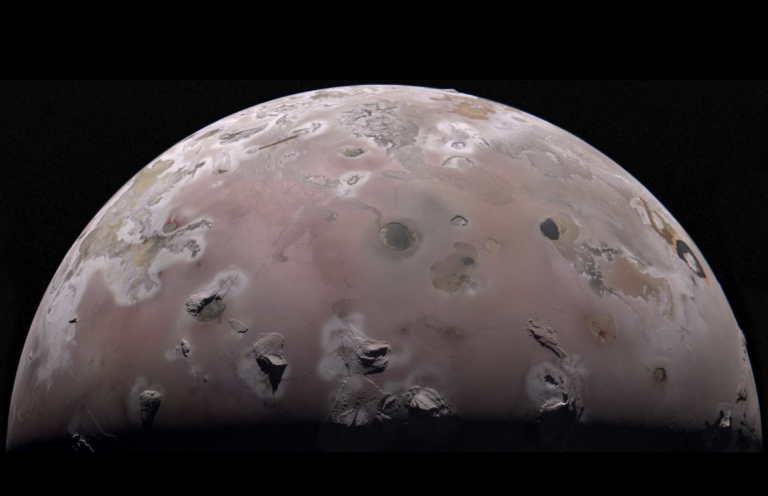

While the researchers have yet to confirm the presence of an exomoon, they estimate that this moon would be about the size of Neptune. Teachey said that it’s likely this possible exomoon is “in some ways the lowest hanging fruit. We should expect to see something like this before we see the really small moons.”

These researchers also found that the exoplanet passed in front of its star about 80 minutes earlier than they anticipated. This observation suggested transit time variations, which is a major signal that there could be an exomoon. “It’s certainly plausible that another planet in the system could induce transit timing variations,” Teachey said. However, during its four-year mission, Kepler found no evidence for a second planet in the stellar system.

Still, it is possible that there is a second planet in the system external to Kepler-1625b whose transit we can’t see, Teachey said. But currently, “we do obviously think that the moon is the best explanation,” he said, adding that “just like any other good skeptical scientist, we’re saying ‘maybe’.”

This still doesn’t prove the existence of an exomoon around Kepler-1625b. To further confirm the exomoon, the team will need to continue to observe the transit events in this system. As stated in a teleconference earlier this week, the researchers will put in a proposal to use Hubble to observe the next transit event in May 2019.

These findings were published in the journal Science Advances on October 4, 2018.