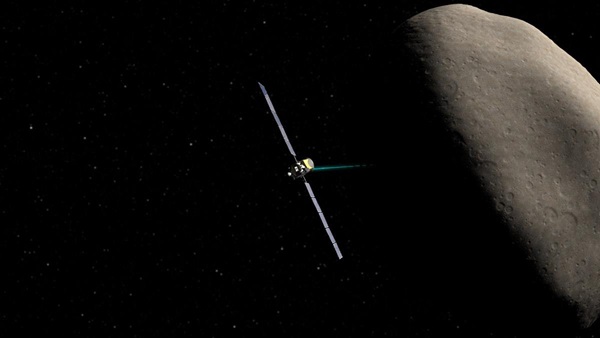

The spacecraft’s end is not unexpected — it’s been running out of hydrazine fuel, which allows it to control its orientation for communications and recharging its solar panels, for months. In July, NASA announced they expected the fuel to run out sometime between August and October; Dawn lasted until the very end of that window, finally missing its check-in via NASA’s Deep Space Network on October 31. A second missed communication on November 1 prompted the team to conclude the fuel had run out, and Dawn is now dark.

“Today, we celebrate the end of our Dawn mission — its incredible technical achievements, the vital science it gave us, and the entire team who enabled the spacecraft to make these discoveries,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, who serves as associate administrator of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, in a press release. “The astounding images and data that Dawn collected from Vesta and Ceres are critical to understanding the history and evolution of our solar system.”

Dawn Mission Director and Chief Engineer Marc Rayman said of the spacecraft, “The demands we put on Dawn were tremendous, but it met the challenge every time. It’s hard to say goodbye to this amazing spaceship, but it’s time.”

Dawn’s science

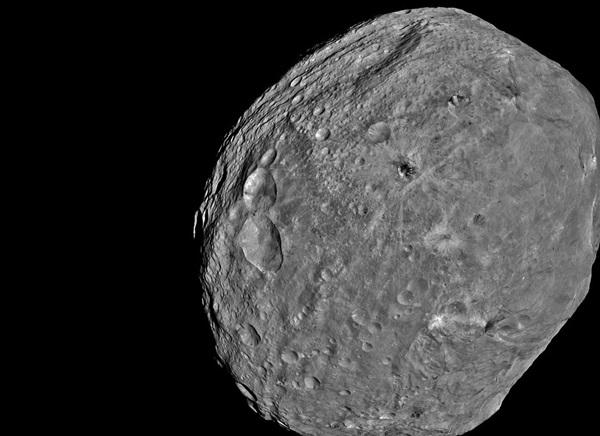

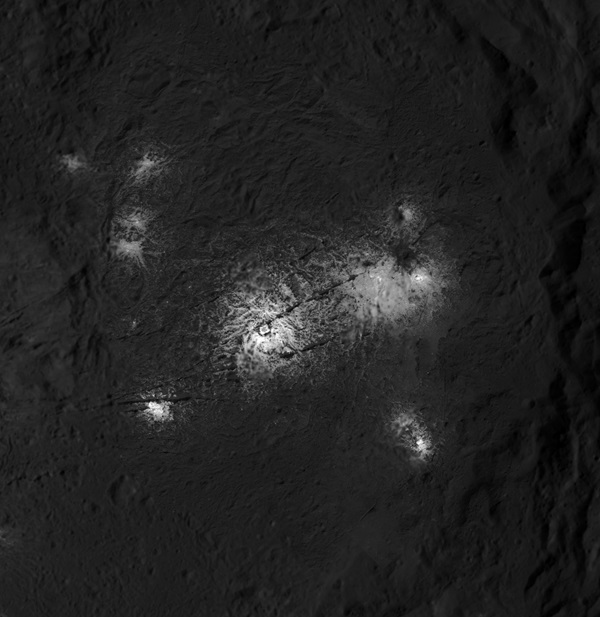

The Dawn spacecraft carried a science payload of four instruments: Framing Camera, Visible & Infrared Spectrometer, Gamma Ray and Neutron Detector, and Gravity Science. It used these packages to explore our asteroid belt in new ways, revealing information unattainable via other means. Dawn returned three-color and black-and-white images of Ceres and Vesta, as well as surface maps using its spectrometers (which break light up by wavelength), which allowed researchers to determine the composition of their surfaces. Radio tracking allowed Dawn to send back information about the worlds’ masses and rotational properties, which shed light on their invisible interiors.

Some of the spacecraft’s major discoveries include showing that dwarf planets are capable of hosting liquid oceans, as well as allowing researchers to compare bodies at different distances from the Sun and map out how location has affected their formation and evolution. At Vesta, Dawn strengthened the connection between the asteroid and certain types of meteorites found on Earth, lending credence that the latter formed when the asteroid was struck in the past. It also mapped out deposits of strange, dark material on Vesta’s surface, which may be further evidence of an impact that threw the material from the impactor across the asteroid.

At Ceres, Dawn discovered evidence for cryovolcanism, an analog to volcanism in which cryovolcanoes spew water and other organics, rather than molten rock. Dawn imaged landslides on the surface of the distant world, spotted signs that Ceres once hosted a liquid ocean, and allowed researchers to better map the dwarf planet’s topography.

The mission’s vast dataset will continue to be available to researchers, allowing for many additional discoveries and studies for years to come. Particularly with the discovery of ‘Oumuamua, a comet from another solar system, Dawn’s data on Ceres and Vesta will help scientists rewind the clock to better understand how planetary systems — our own and others — form.

Mission’s end

With the depletion of its hydrazine fuel, the Dawn spacecraft would have entered several safe modes as the onboard computer attempted to identify and rectify the issue. But there is no solution for a lack of fuel, and though the spacecraft would have shut down its systems and run off battery power, that battery cannot be recharged if the craft is unable to orient its solar panels toward the Sun. One of the systems it would have shut down is its radio, to be turned on only after power was restored — a situation that will not occur without the ability to point.

In its 11 years, Dawn has traveled a total of 4.3 billion miles (6.9 billion kilometers) and accomplished a long list of firsts. Now, it will remain in orbit around Ceres for decades, circling the world for at least 20 to 50 years. That’s intentional, as Ceres has conditions that could be right for life, and engineers want to prevent contact between the spacecraft (and any potential Earth microbes it may carry) and the dwarf planet. Planetary protection protocols currently in place prohibit it from touching the surface for at least 20 years, which is enough time for a potential follow-up mission if the world is given a higher priority for protection.

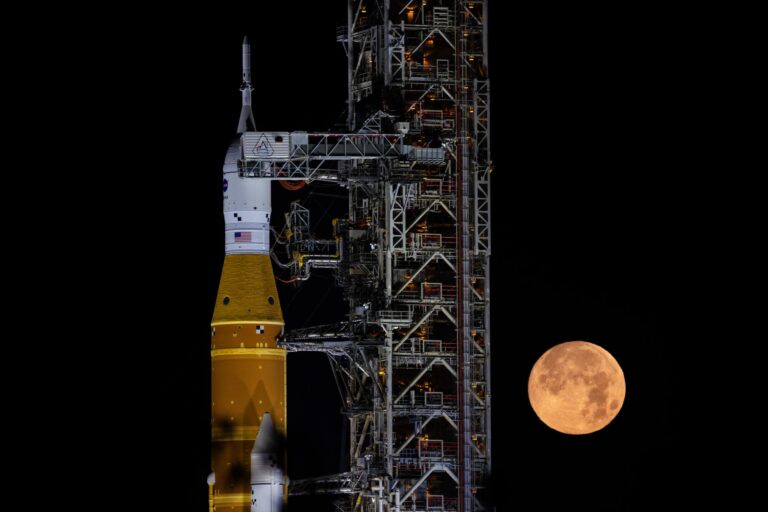

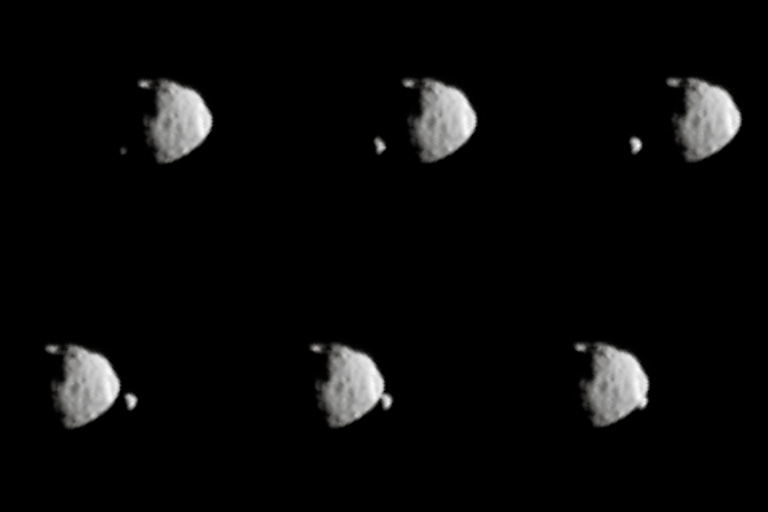

The end of the Dawn mission comes only two days after NASA’s Kepler space telescope was also retired due to a lack of fuel. Though both endings were expected losses, both have silver linings. Not only do these two amazing spacecraft leave behind an immense wealth of data, they are also succeeded by other projects. Hayabusa2, currently in orbit around the asteroid Ryugu, has sent several landers to its surface and will gather samples of the asteroid before returning to Earth in a few years. Comparing those samples to what researchers have learned about Vesta and Ceres will bring our picture of the solar system’s past and present into ever-sharper focus.