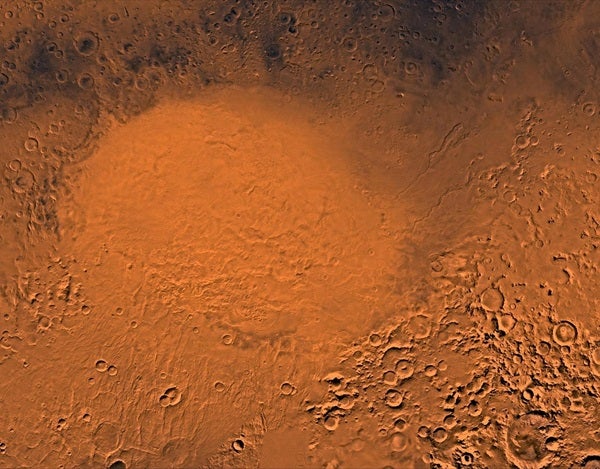

A new study reveals that the Hellas impact basin on Mars once contained a number of ephemeral lakes, or lakes that are usually dry but fill up with water for brief periods of time.

Watery World

Located in the Red Planet’s southern hemisphere, the Hellas impact basin’s northeastern rim had many of these temporary lakes throughout Mars’ history, say researchers from the SETI Institute. The depressions were filled with water from a variety of sources, they say, including groundwater, snowfall, rivers and streams.

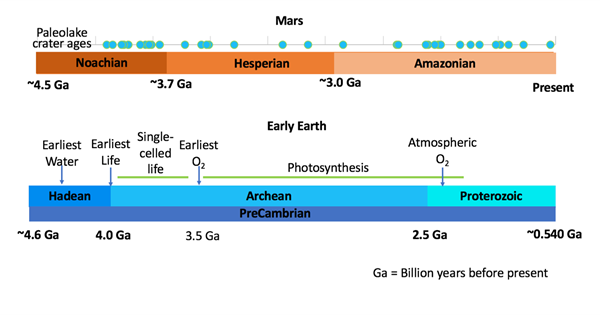

Known as paleolakes, these ancient martian lakes were active when Mars’ climate was drastically different than it is today. One of the paleolakes is almost completely filled with smooth sediment, the researchers found, which is similar to what scientists have seen in the saline lakes in the Andes mountains. This similarity suggests that the conditions on Mars when this paleolake formed could have been like the conditions in the Andes mountains today — cold and arid.

The paleolakes were found along water drainage systems that led to smaller depressions in the surface, or “lakes,” at the edge of Hellas Planitia, a plain within the impact basin. The lakes weren’t all the same, either. Some may have served as the source for channel systems hundreds of miles long, while other may have had rivers flowing through them. Still others bear the scars of likely flash floods.

“In the highest resolution images, we could see sediments, deposits, and what looked to be shorelines in some cases in these craters and depressions that the channels flowed into,” Virginia C. Gulick, a SETI senior research scientist and study researcher, said in an email.

This research could be important in the search for life, potentially providing evidence for past microbial life on the planet. “Areas where water was periodically available over long periods of Mars’ history, especially if they were associated with volcanic magma hydrothermal systems, could have provided the habitats suitable for microbial life if it ever arose,” Gulick said.

This new study was published October 30 in the journal Astrobiology Volume 18, Number 11.