Abandon sky!

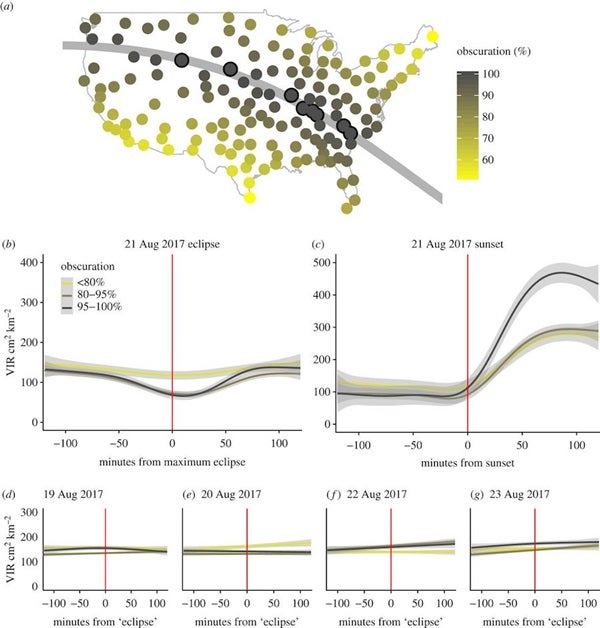

One such group of researchers, led by Cecilia Nilsson of Cornell University, decided to use an expansive network of 143 weather radar stations scattered across the country to study whether the oddly timed darkness of the eclipse would cause flying animals — such as birds and insects — to flood the skies like they typically do at sunset.

According to the study, it didn’t.

In fact, as the eclipse darkened the sky, the researchers were surprised to find that biological air traffic seemingly decreased overall. And based on this finding, the team was able to draw a few main conclusions.

First, diurnal critters (which are typically active during the day and inactive at night) seemed to have abandoned the air for the ground as the Moon slowly blotted out the Sun. This finding lends some credence to many anecdotal reports of decreased chirping and increased roost-like behavior in birds during eclipses. Second, the researchers found that darkness cues from the eclipse were not strong enough to cause nocturnal animals to take flight as if it were sunset.

According to the study, “This pattern suggests that cues associated with the eclipse were insufficient to initiate nocturnal activity comparable to that occurring at sunset but sufficient to suppress diurnal activity.”

Bee quiet

Interestingly, the idea that insects strongly and quickly change their behavior during a total solar eclipse is one that is supported by another study just published last month in the Annals of the Entomological Society of America. In the study, researchers from the University of Missouri organized a slew of citizen scientists and elementary school classrooms to acoustically monitor how totality influenced the behavior of bees.

The results were astoundingly clear: Bees stopped buzzing during the total solar eclipse.

“We anticipated, based on the smattering of reports in the literature, that bee activity would drop as light dimmed during the eclipse and would reach a minimum at totality,” said lead author Candace Galen, in a press release. “But, we had not expected that the change would be so abrupt, that bees would continue flying up until totality and only then stop completely. It was like ‘lights out’ at summer camp! That surprised us.”

“The eclipse gave us an opportunity to ask whether the novel environmental context — mid-day, open skies — would alter the bees’ behavior response to dim light and darkness,” explained Galen. “As we found, complete darkness elicits the same behavior in bees, regardless of timing or context. And that’s new information about bee cognition.”

Next up…

Although there was a 40-year hiatus between the previous two total solar eclipses in the continental U.S., fortunately, Americans don’t have to wait nearly as long for the next. On April 8, 2024, a total solar eclipse will make its way up through Texas, slide across the heart of the country, and end in Maine — and countless researchers are sure to again monitor how the eclipse affects wildlife all over the United States.