Even just 30 days in space can significantly reduce our immune system’s ability to fight infection, suggests a new analysis of mice that spent a month aboard an orbiting spacecraft.

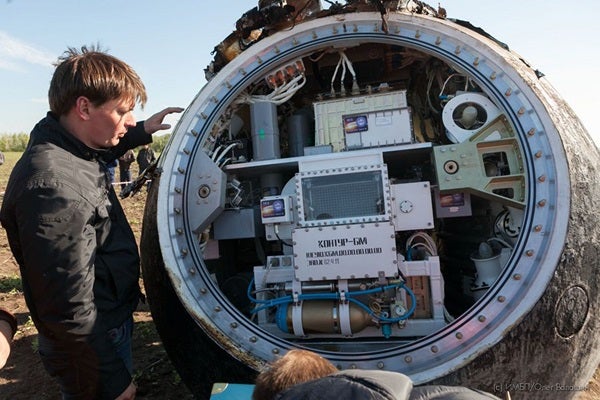

The research, which was published December 6 in the journal Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, is a recent analysis of data from the Bion-M1 mission, which was a collaborative project carried out by NASA and the Russian Institute of Biomedical Problems in 2013.

As part of the study, an international team of researchers compared three distinct groups of mice. The first two groups spent 30 days orbiting the Earth at an altitude of 360 miles (575 kilometers), while the third group, which served as the control, remained on the planet under similar feeding and housing conditions. Of the two space-bound groups of mice, one was examined immediately following its return to Earth, whereas the other was evaluated a week later.

According to the study, which analyzed proteins found within the rodent’s femur bones, the researchers revealed that living in a microgravity environment for even 30 days is enough to dramatically impair the mice’s ability to produce vital immune system cells, and this effect persisted even after a week safely back on Earth.

Specifically, the space-bound mice experienced more than a 40 percent reduction in their number of B lymphocytes (or B cells). Since these lymphocytes are white blood cells that are necessary for the production of antibodies, the researchers say the dearth of B cells may help explain why many organisms — including astronauts — tend to be more susceptibility to infection during stints in space.

“We hope these finding will encourage exploration of countermeasures to improve astronauts’ health and increase the safety of spaceflight,” said co-author Fabrice Bertile, a researcher at the Hubert Curien Multidisciplinary Institute’s Analytical Sciences Department in France, in a press release. “Such concerns are of major importance at a time when space agencies are envisioning manned missions to the Moon, asteroids, and even Mars in the near future.”

But these new insights into how spaceflight affects the immune system are not only applicable to astronauts. Considering a significant number of people on Earth are immobilized or lead sedentary lives, future research on how microgravity impacts the immune system may have serious implications for millions of Earth-bound residents.

Moving forward, the researchers suggest future studies should explore whether longer missions are more detrimental to the immune system than shorter ones, as well as investigate how the antibodies produced in a microgravity environment are qualitatively different from those produced on Earth.