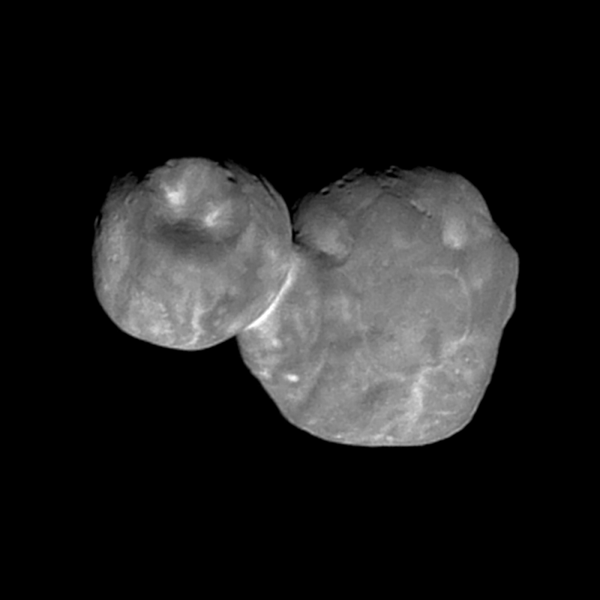

This latest image was taken with the wide-angle Multicolor Visible Imaging Camera (MVIC) component of the spacecraft’s Ralph instrument. The camera snapped the shot when the spacecraft was just 4,200 miles (6,700 km) from the object, at 12:26 a.m. EST, just seven minutes before the craft reached closest approach on Jan 1.

This newest image had an original resolution of 440 feet (135 m) per pixel. After beaming back to Earth between around Jan. 18, scientists enhanced the details of the image to make it as clear and sharp as possible. Though, this process (known as deconvolution) will make the image look a bit grainier at high contrast.

The new image shows Ultima Thule’s surface along the day/night boundary near the top of the object. You can also make out a number of small pits on the surface, which stretch nearly half a mile across. You might notice a large, circular feature on the space rock’s smaller half. Using this image, it appears as though this feature, which stretches about 4 miles (7 km) across, is a depression.

It is too early to definitively say whether these features are impact craters or created from internal processes. Both halves, or lobes, of the object also have light and dark patterns. The most obvious of these is the light band that separates the object’s two lobes. Scientists don’t yet know where these patterns came from, but according to a statement from Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, they could help researchers to decipher the object’s origins and how it formed.

“This new image is starting to reveal differences in the geologic character of the two lobes of Ultima Thule, and is presenting us with new mysteries as well,” New Horizons Principal Investigator Alan Stern said in the statement. “Over the next month there will be better color and better resolution images that we hope will help unravel the many mysteries of Ultima Thule,” he added.