Repeating FRB

For just the second time, scientists have recorded the repeat of a mysterious cosmic flash know as a fast radio burst (FRB). This remarkable observation could help scientists to better understand this phenomenon and where these bursts originate in the universe.

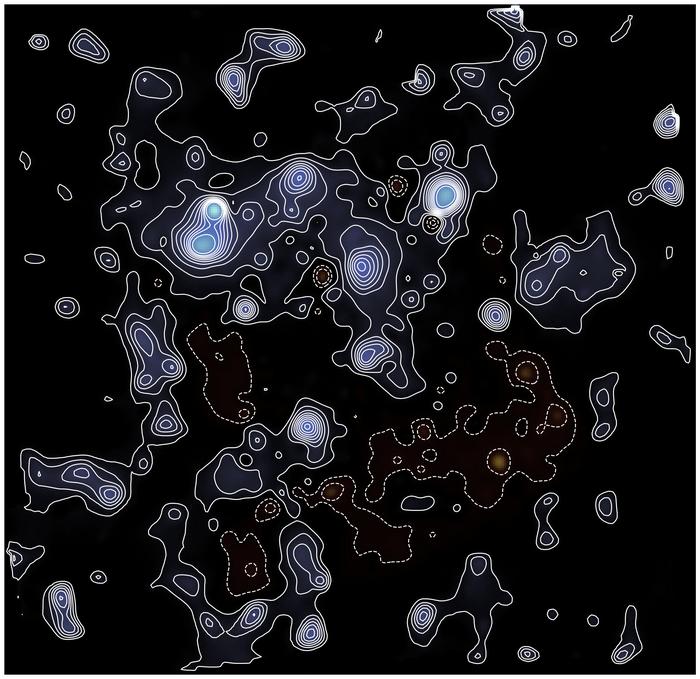

FRBs are extremely brief (think millisecond) flashes of radio waves that originate from random (as far as we can tell) places in the cosmos. Astronomers have grappled with this mystery for years because, while they continue to observe bursts, they are still unsure of what causes them. “We estimate that there are up to 1,000 of these bursts in the entire sky every day,” corresponding author Shriharsh Tendulkar of McGill University said in an email.

But, until this most recent work, only one repeating FRB, known as FRB 121102, had been observed. Every other FRB has flashed once and then disappeared. But now, using the Canadian Hydrogen Intensity Mapping Experiment (CHIME) instrument, researchers have detected a second such repeating event. Excitingly, it bears striking similarities to the first repeating FRB.

This repeating FRB is one of thirteen (the rest are single bursts) announced today by scientists.

“These are extremely powerful and frequent bursts. We have never seen anything like this before. The closest analogs we have in our own galaxies (pulsars) are more than a trillion times fainter,” Tendulkar said about the repeating FRB. Additionally, “this second source shows burst behavior (i.e. multiple structures in the burst) that is extremely similar to the first repeating FRB and which is different from all the single FRBs,” Tendulkar said.

Exploring the Universe

The new repeating FRB has another unusual characteristic as well. While most other FRBs detected were recorded at between 1400 megahertz (MHz) and 2000 MHz, these bursts were found at 400-800 MHz, far lower than ever before.

“Now we know that FRBs are detectable at 400 MHz, and should be detectable at even lower frequencies,” Tendulkar said. 400 Mhz is the lower limit of the CHIME experiment at the moment, so other FRBs at lower frequencies could simply be going undetected.

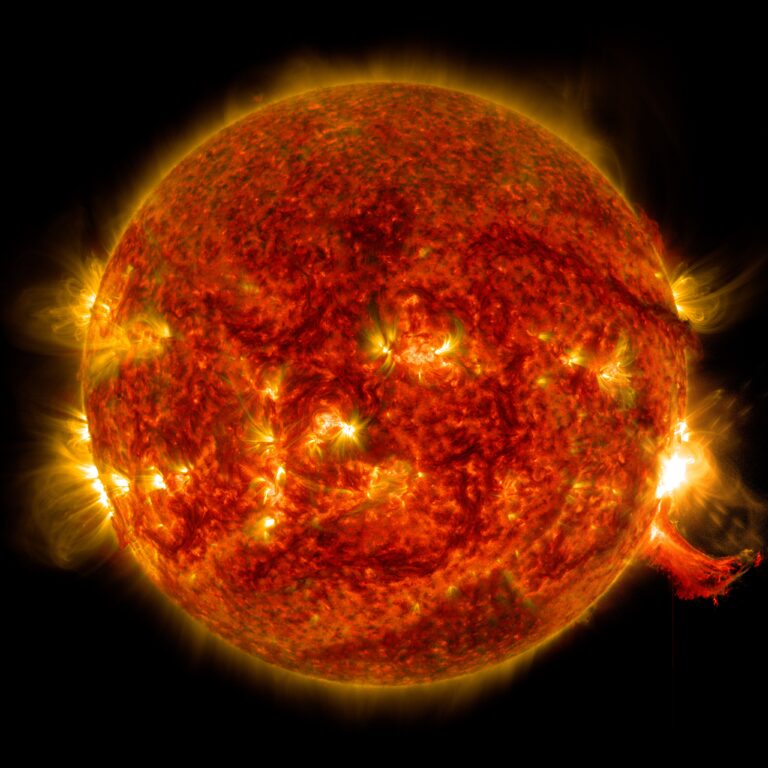

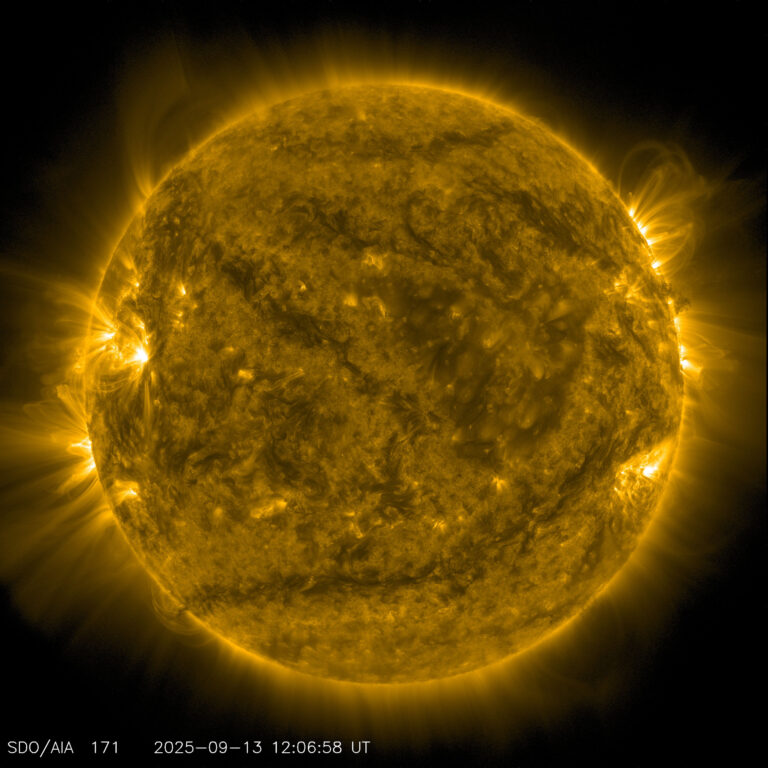

These observations could help scientists to better understand the universe at large. “We would like to know what kinds of objects these are and how they are related to other explosions and objects that we know of (gamma-ray bursts, supernovae, neutron stars etc),” Tendulkar said. “It helps us build a more complete picture of the Universe.”

She adds that studying these bursts “can help us probe the distribution of electrons (hence of matter in general) and magnetic fields in the Universe in ways independent of other methods that we have developed. This allows us to study how structures in the Universe formed and how they are distributed.”

This work was published today (January 9) in a set of papers in Nature.