After some 15 prolific years on the Martian surface, NASA’s Mars Opportunity rover has gone silent. And after an all out effort to re-establish contact, the space agency says it’s given up hopes of ever hearing back from the rover. We talked to the NASA engineers and scientists whose lives have been touched by the Opportunity rover about their experiences and what the craft meant to them. For some researchers, the mission has encompassed their entire career. For others, the spacecraft team was like a tight-knit family that will soon go its separate ways.

Their eulogies for the lost rover are below. Some have been condensed for space and clarity.

Scott Maxwell, former rover planning lead for Mars Exploration Rovers (MER) Spirit and Opportunity

Maxwell drove the rover for nine years before leaving the mission and NASA in 2013.

“Put simply, I loved Opportunity, as I did her twin sister Spirit. I was privileged to be part of a team that was ecstatically devoted to them for years. We sacrificed dinners with family, vacations, whole marriages, to those rovers.

And they were worth it: in exchange, they gave us a planet. They were our eyes and ears, our remote robot bodies, as we made a god into a place. Our daughters, alongside whom we were lucky enough to walk a while.

The thought of saying goodbye to Opportunity fills me with … with mixed emotions. Pride, certainly, at her enormous accomplishments. But grief and despair at her loss. And truthfully, I think the pride will have to wait a while. There’s no room for it now.”

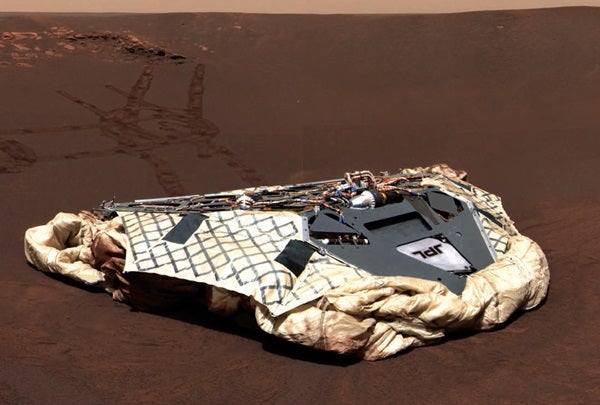

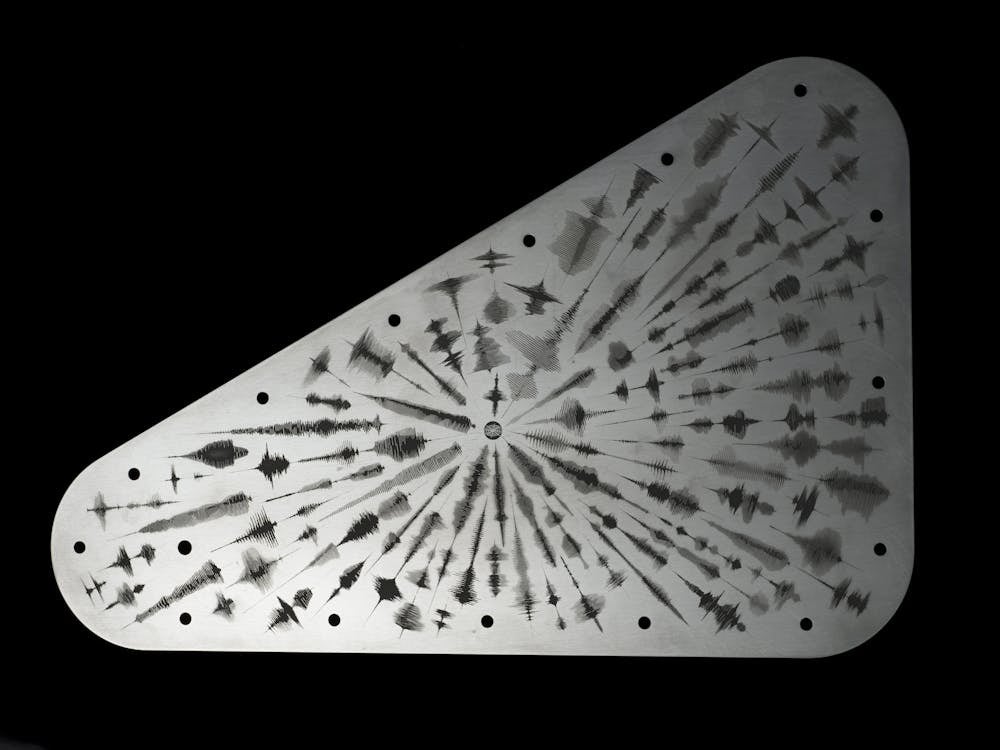

NASA/JPL/CORNELL)

Tanya Harrison, Director of Research for the Space Technology and Science (“NewSpace”) Initiative at ASU and Science Team Collaborator on the Mars Exploration Rover (MER) Opportunity.

Harrison’s research has focused on the role of water in Mars’ history — something Opportunity has played a role in uncovering.

“If I had the chance to say one last goodbye to Oppy, I would thank her for her tireless service above and beyond all possible expectations. There’s probably no more fitting way for her to have gone than in the strongest dust storm we’ve ever seen on Mars — for her, I would expect nothing less. Now she can rest, beneath a thin layer of dust, knowing she did humanity proud.”

Mike Siebert, former Opportunity rover planner

Siebert started on the mission in 2005 as a tactical activity planner / sequence integration engineer, eventually becoming a flight director for the mission and rover planner.

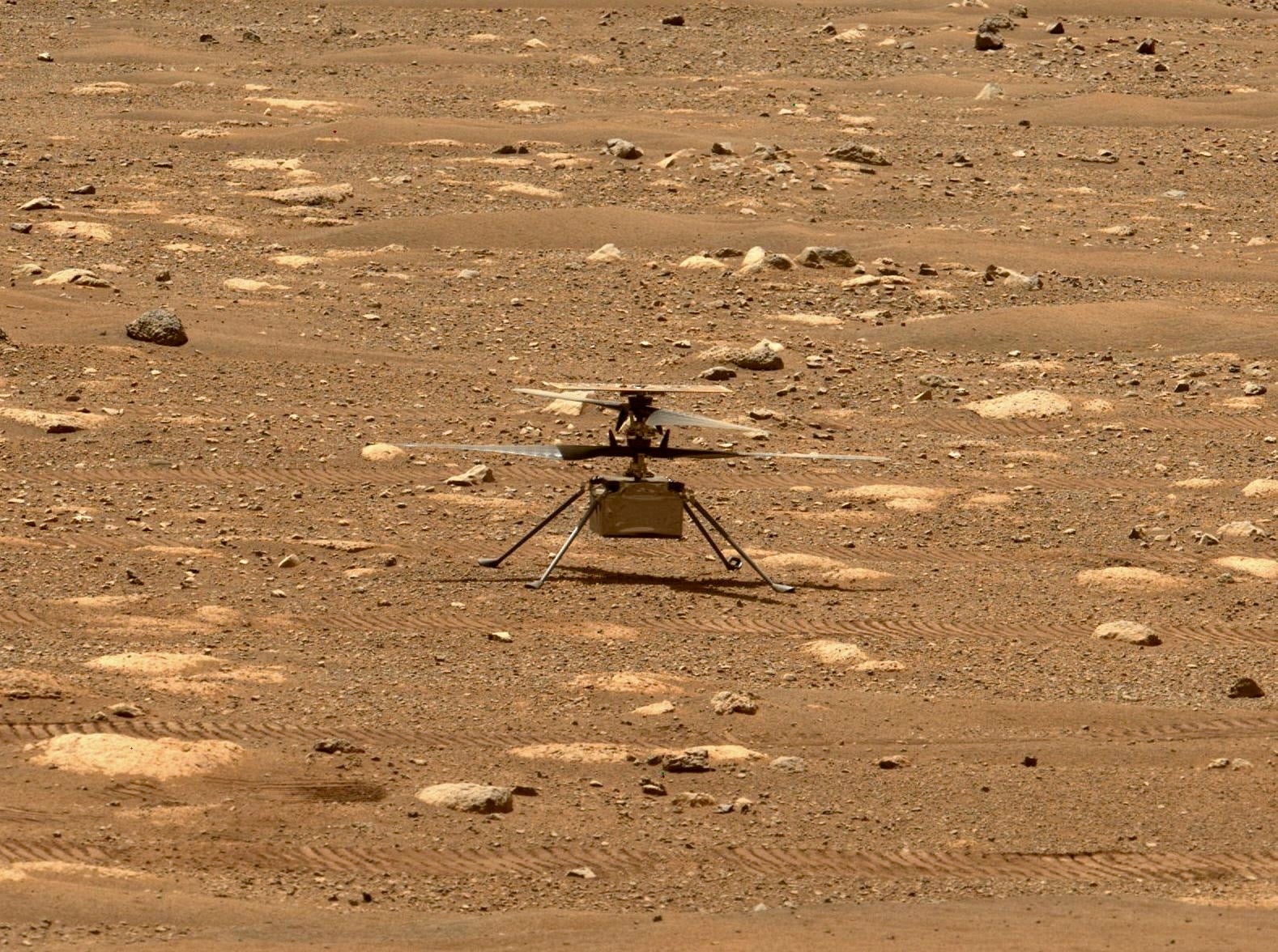

“[Opportunity is] the longest lasting mission we’ve had on the surface. That rover was basically driving until the end. It deployed its IDD [the rover’s arm] shortly before the storms started. My understanding is that the arm is actually placed on the ground. They’ve got an instrument down ready to do science. The fact that you’ve had a functioning mission for this long … it set a bar awfully high for Mars exploration. Mars 2020 is going to really have to work to best Opportunity. It’s appropriate that Perseverance Valley is where the Opportunity rover rests.”

Keri Bean, Science Planner on Opportunity

Bean is a former NASA Dawn spacecraft mission scientist who has since become part of both the Opportunity and Curiosity teams.

“Because (Opportunity has) such a small team, we have a lot more of a family feel, and that’s something I haven’t really found in any of the other projects I’ve worked on. We’re all really close, we hang out on the weekends, we go out to dinner, and I haven’t really gotten that vibe with any other project. Not that we’re not friendly on other projects, just that this seems to hold a special place in our hearts and that we bond together.

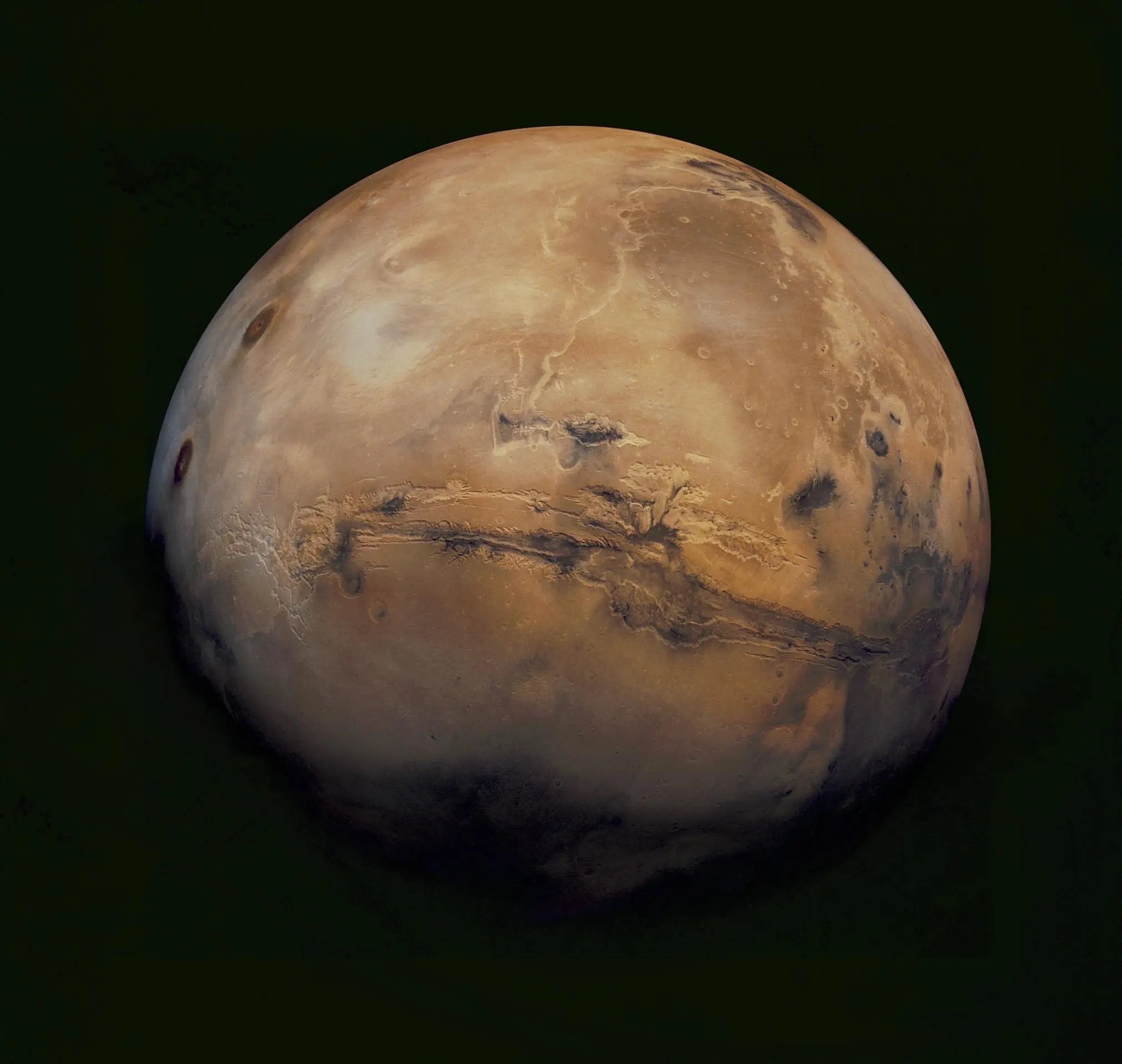

I think Opportunity’s made the solid case that at least in some point in the past, Mars was habitable. We don’t know when, we don’t know if it ever happened, but at least there were several spots on Mars where we could have potentially had life whether now or in the past and I think that’s really fascinating.

For me personally, I think Opportunity has always just kind of always persevered. Mars has thrown a heck of a lot at her. This isn’t even her first global dust storm. She’s survived so much. Parts have broken along the way. There’ve been problems along the way. Yet every single time, we’ve overcome it and this is finally the one we can’t overcome. It’s kind of bittersweet that she’s dying in Perseverance Valley. I wish she could have persevered a little longer, but Mars had other plans.

The team has certainly had its ups and its downs and some people have had to leave to other projects already. We’re running on a skeleton crew at this point. It’s sort of sad to see this family disbanded.”

Abby Fraeman, deputy project scientist

Fraeman has been involved with the mission since she was a teenager, moving from a student program sponsored by the Planetary Society where she was able to witness the rover landing, to working as a summer associate in undergraduate and graduate research before becoming a member of the team.

“In terms of the science accomplishments, Opportunity was the first rover to find evidence for liquid water on the surface of Mars. Before that we didn’t have any definitive evidence. It was the first rover to look at sedimentary rocks on another planet. We learned a lot about how to drive rovers on another planet using Opportunity.

We’ve looked at rocks from two very different periods in Mars’ history, and we found evidence for two very different environments during the time periods, which is important for constraining the evolution of the planet as a whole. We found the earlier rocks probably formed in an environment that could have hosted life. We’ve also kind of learned more about processes that govern the solar system like impact cratering. We’ve studied hundreds of craters, including the biggest one we’ve spent the past few years looking at, Endeavor Crater, and this helps us understand more of this process that’s so important for the solar system.

Another legacy that I think is important from my personal story is the legacy of inspiration. I know I’m not the only one who has a story who thinks that Spirit and Opportunity flipped a switch in their heads and said “oh my gosh, I’d love to pursue a career in math or in science to be able to something like this for a career,” whether it be a rover or doing science. I think that’s another important legacy that’s a little bit harder to quantify, but it’s just as important as the science results that have come out.”

Ashley Stroupe, rover planner, Opportunity; Curiosity engineering team

Stroupe served with Spirit and Opportunity starting on Spirit’s sol 289, roughly one month into the Opportunity mission. She has since risen the ranks and brought her experience to the Curiosity team.

It’s sort of bittersweet. We lasted almost 15 years for a three-month mission. We made multiple scientific discoveries that fundamentally changed our understanding of Mars, in a way that has guided all of the future exploration that we’ve been doing since the Curiosity Rover. And to have been a part of that, and to have had it be so much more successful than anybody’s wildest imagination, is a really wonderful thing.

It’s going to be a sad day, but it’s also going to be a day to celebrate in a way, because what we’ve accomplished is incredible and honestly may never be matched again.

I think the real scientific legacy is that Opportunity was the first confirmation on the ground using chemical signatures and other things that we had, prevalent water, flowing water on the surface of Mars, and for a long period of time, that it wasn’t just a single moment in time. It wasn’t just groundwater. It really proved that these formations that we see from Earth that look like old river channels and other things probably really were water carved, and that the water was there consistently and for a long period of time. And I think that’s going to be one of the real legacies.

The other one I really think is the engineering legacy. We’ve accomplished things with engineering that, like I said, nobody could have imagined when we started. Being able to operate rovers in the difficult terrain, steep slopes, sand, and with diminishing capabilities. That has really informed how we design all of our future rovers.

I mean, things that we had to do to survive with Spirit and Opportunity have now become fundamental built in parts of Curiosity and 2020. And again, I don’t know that we’ll ever have another surface asset that contributes as much for as long. I certainly think that the distance that we’ve driven may be the longest we drive off the planet for a very long time to come. And just being able to look at that and say, “Look at what we can achieve.” I think that will be the other half of its legacy.