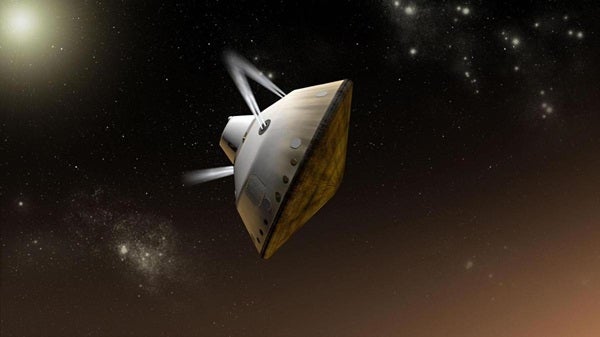

At the moment, most spacecraft rely on parachutes to slow down from a whopping Mach 30 or so as they enter the Martian atmosphere. And once those landers are traveling at a more reasonable speed of a few times the speed of sound, engineers have a variety of options to touch down softly.

But those parachutes just aren’t effective for larger craft — they don’t scale well. That prompted aerospace engineers Christopher Lorenz and Zach Putnam to explore other options in a recent paper, published Dec. 31, 2018 in the Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets.

We’re Gonna Need a Bigger Spacecraft

The heaviest craft that’s reached Mars’ surface is the Mars Curiosity rover, at about 2,200 pounds, or just over 1 ton. But crewed spacecraft will likely be much heavier, between five and 20 tons.

That will require using retrorockets to slow the spacecraft, like the ones SpaceX and Blue Origin fire to land their boosters. But this burns a lot of fuel – fuel that must be lifted off Earth (requiring even more fuel). And it takes up cargo space that could otherwise hold human explorers or valuable equipment and supplies.

Fuel for landing maneuvers is therefore at a premium, and mission planners must judge carefully how they spend that fuel, while still making sure to land their spacecraft in a safe location and at a safe speed.

“Once the descent engines are ignited,” Putnam said in a press release, “the engines have a certain amount of propellant. You can fire engines in such a way that you land very accurately, you can forget about accuracy and use it all to land the largest spacecraft possible, or you can find a balance in between.”

You can also steer the vehicle while it’s still moving hypersonically. The Space Shuttle was notorious for being a “flying brick,” but it could be steered. By angling or unbalancing any spacecraft already in motion, engineers can create lift that steers their craft in a given direction – even in Mars’ relatively thin atmosphere.

(As a reminder, a plane doesn’t have to use its engines to turn. If the plane lowers one wing, the entire craft will turn in that direction due to lift.)

This means that mission planners can steer their spacecraft before firing the braking thrusters and burning valuable fuel. They can conserve fuel by carefully choosing both the altitude and angle of the spacecraft for when they do fire the rockets. This lets them fly closer to their intended landing target without burning fuel for steering, while also minimizing the amount of fuel needed to slow the craft.

After considering multiple scenarios, the authors concluded that the most efficient flight path (i.e., the one that burns the least fuel) is to dive nearly straight into the atmosphere at first. The vehicle can then lift up, flying at low altitude where the atmosphere is thickest and produces the most drag on the craft. By using simple physics to slow the craft, mission planners can use less fuel, and therefore pack more science into their future heavy missions.