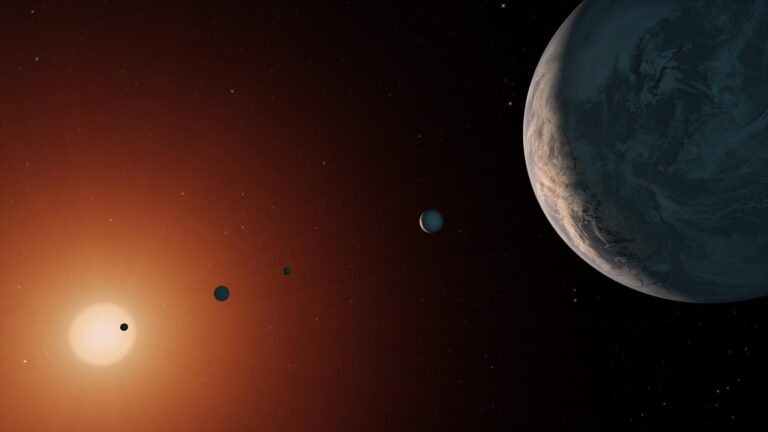

A new global study of ancient Martian riverbeds shows they are wider than Earth rivers on average, and once carried large volumes of water and runoff. They also flowed until surprisingly recently in Mars’ history, perhaps into the last billion years. This is a puzzle, given the Red Planet’s current desert environment, its thin atmosphere and dim sunlight. These features should have prevented vast water resources even early in the world’s history. Now scientists must puzzle out how both sets of evidence can co-exist – or prove one wrong.

Wet and dry riverbeds

Researchers from the University of Chicago, led by Edwin Kite, looked at ancient riverbeds across Mars, and published their findings March 27 in the journal Science Advances. The team says they were surprised to find potential evidence for heavy water flows in the last billion years.

That’s well into the time period when astronomers think Mars was losing its atmosphere and drying out. How a planet with so little sunlight and atmosphere stayed warm enough to host – not just a little surface water, but fast-flowing rivers – is hard to figure out. The researchers stress that while the water may have appeared and disappeared over long periods of time, when it was there, that water filled riverbeds across the planet, in more than 200 locations they studied.

In an interview, Kite said that something else must be wrong if the riverbed data is correct. Maybe the rivers are older than researchers think. Or perhaps Mars dried out much faster than current theories suggest. But Kite says some strange process may have also kept Mars warm long enough for large rivers to flow even after most of its atmosphere had disappeared.

“All three options are uncomfortable,” Kite says. “All three of these solutions would require significant revision of our current understanding.”

Kite points out that the first possibility could be explored with a sample return mission that would let scientists find concrete ages for the riverbeds they see from orbit. While sample return plans are underway, that mission is still years off. That leaves scientists stuck trying to explain how Mars, which is farther from the Sun than Earth, stayed warm enough even though the young Sun was even less bright than it is now. Yet the latest evidence overwhelmingly indicates that Mars was once a very wet world.

For the second option, Kite says that NASA’s orbiting Mars MAVEN mission has returned convincing evidence that the solar wind slowly stripped the Red Planet of its atmosphere over a long period of time. Revised models would have to explain both MAVEN’s atmospheric data and the evidence of large amounts of recent surface water, which is a tricky balance.

The third option of keeping Mars warm even with a thin atmosphere would depend on some kind of greenhouse warming effect. And Kite says the most likely cause of a Martian greenhouse effect would be water ice clouds that would trap infrared light and warm Mars enough to keep water wet and moving on its surface.

Whatever the solution, Mars’ climate history will likely remain a mystery at least a little while longer.