Key Takeaways:

The event was a momentous one for the space artists who have spent decades drawing black holes in the absence of actual confirmation of what they look like. We spoke to a few of our contributors on what it was like to paint an unseeable object — and how they reacted to their first glimpse of a real life black hole.

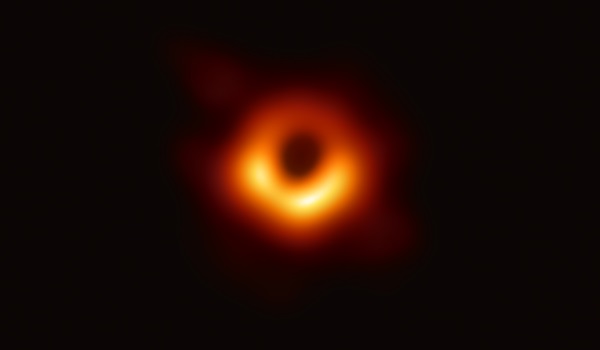

Staring at the Shadow

Adolf Schaller, an artist who has spent more than 35 years painting the cosmos, eagerly watched the press conference that unveiled the first images. “It’s just fantastic to be able to see that shadow,” he says. “It’s a haunting thing. It’s staring right back at us, isn’t it?”

“I’ve been studying black holes carefully for most of my artistic career, and my interest in physics just glommed right onto that,” he says. “At that time, beginning in the early and mid ’70s […] I had already been thinking about black holes — just from my reading on the subject.”

For decades, scientists have used models and their knowledge of the laws of physics to produce simulations of what a black hole might look like, in the absence of an actual picture. For example, computer simulations were invaluable to Schaller when it came to representing how gravity would warp and distort light around the event horizon of a black hole.

A Different Perspective

Painting far-away cosmic objects can also entail putting some unusual queries to data-minded scientists. Michael Carroll, another frequent Astronomy art contributor, has been painting space scenes like planetary vistas and raging stars, since the early 1980s. He says that, for him, being an artist has meant asking scientists unorthodox questions. “Often, the astronomical artists asks questions of the scientists that don’t often cross their minds because they don’t think visually; they’re thinking in terms of numerical data,” he says.

Want to learn more about black holes and other extreme objects in our universe? Check out our free downloadable eBook: Exotic objects: Black holes pulsars, and more.

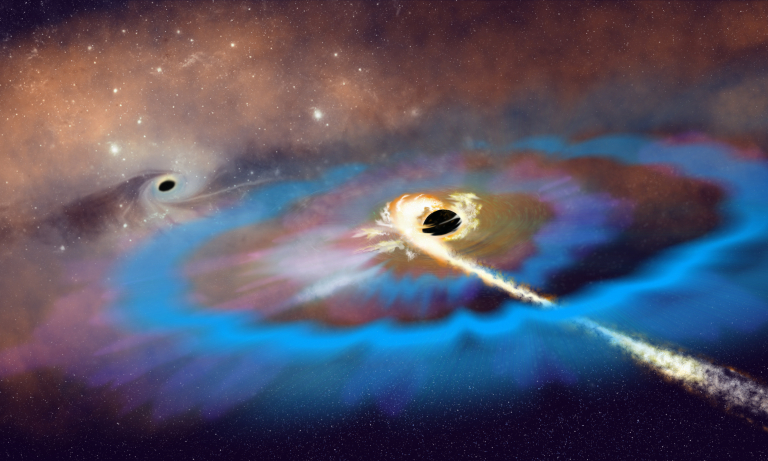

The resulting answers, like what colors might flow out of a black hole or how, exactly, it distorts the light that comes near the event horizon helped fill in his mind’s eye. As his understanding of black holes grew, it deepened some of the ways Carroll opted to portray them.

“You begin to see that it doesn’t really suck light in, it bends the space-time continuum around itself so it bends light in,” Carroll says. This creates some interesting visual effects like faint wisps of jet material emanating in an unusual swirl pattern from the event horizon.

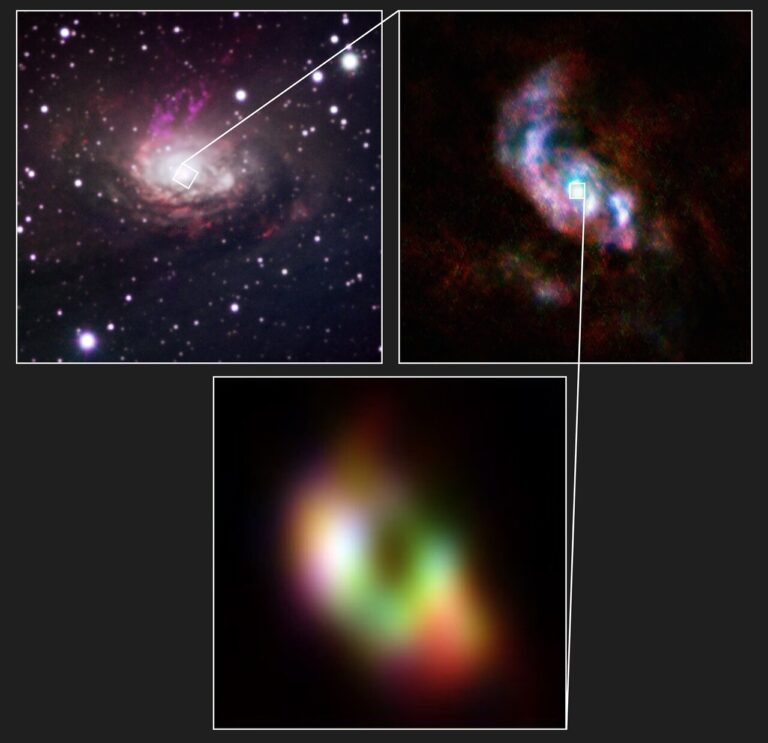

But for Carroll, there are still unanswered questions. For instance, what happens to the infalling matter near a black hole? What are the structures of the jets like? Are there dozens of explosions from matter colliding near a black hole? And then there are the really close up things. “I would love to see details of the accretion disc,” he says. “What does the texture look like around that black hole? What colors come out in the visible spectrum?”

Those are questions that will be answered quite a few Event Horizon Telescope upgrades down the line.