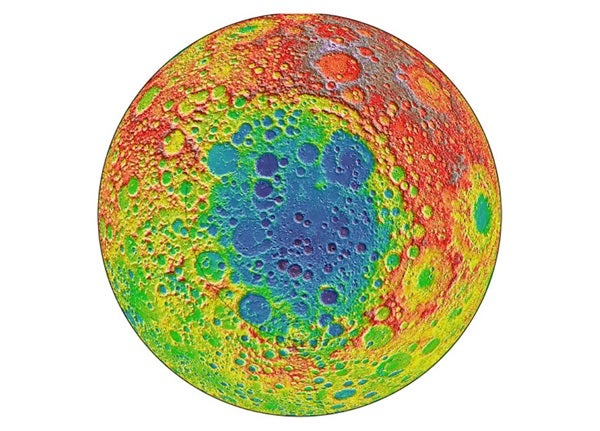

Since January, China’s Chang’e-4 mission – an orbiter and a rover – has been exploring the far side of the Moon, particularly the prized South Pole-Aitken Basin, an asteroid impact crater that stretches across nearly a quarter of the Moon’s surface. It’s the biggest crater on the Moon, as well as the deepest and the oldest. That’s long left scientists suspecting that Aitken may hold vital clues as to how the Moon – and many other solar system bodies – evolved.

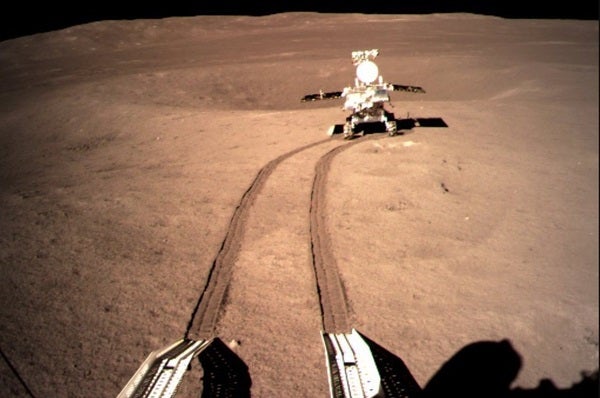

Now, the Chang’e-4 mission’s Yutu-2 rover, which is still driving across Aitken Basin, has finally discovered Moon dirt that researchers think originated deep underground in the Moon’s mantle, underneath the lighter surface material. Meteor impacts into Aitken Basin’s already-thin crust may have excavated this material, which is markedly different from the surface rocks and regolith most lunar missions have studied. And by examining those minerals, scientists say they now have a better idea of how our Moon formed and evolved.

Meteor Miners

The Moon formed early in our solar system’s history when Earth smashed into a Mars-sized planet called Theia. And like many large solar system bodies, researchers think that when the Moon was very young, it was covered with a magma ocean. As the Moon cooled, the heavier materials sank toward the lunar core, while the lighter material floated to the top, where they were preserved as the lunar surface we see today. In between these is a medium layer called the mantle. And unlike the Earth, with its volcanoes and plate tectonics and deep ocean rifts, the Moon hasn’t reshuffled its layers very much. So the only way to bring the heavier materials to the surface is likely through meteor impacts that hit hard enough to break through the surface layers to the deeper mantle underneath – especially millions or billions of years ago when that lower layer was still molten.

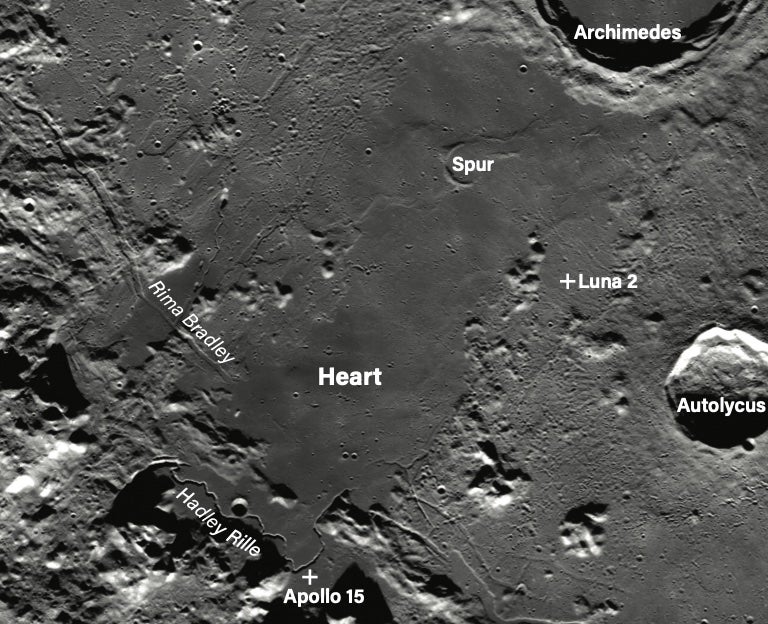

The most likely place for this to have happened is the Aitken Basin, where one huge impact carved out an extremely large and deep crater, and almost certainly cracked into the lunar mantle. This should have flooded the area with denser minerals like olivine and pyroxene. The Yutu-2 rover used a spectrometer instrument to explore flat areas in the bottom of this crater, but found only a few traces of those minerals.

However, when it explored craters within the crater – where later meteors struck the already-thin surface – the rover found more of the materials it was searching for. Researchers published their findings May 15 in Nature.

This is strong support for the idea of deeper impacts excavating mantle material that’s made up of different kinds of minerals from the more familiar surface rocks and dirt. It’s a good confirmation for what many scientists had already suspected about what the interior of the Moon really looks like, and that it evolved in the layered way that researchers thought.

But Yutu-2 will keep exploring. While the stories the craters tell is illuminating, the researchers need to be sure that the material truly came from inside the Moon – this means looking carefully at how the material has been moved around by the years and later meteor strikes. And while Yutu-2’s instruments are good, they’re not as good as a hands-on laboratory. The best, most convincing evidence will come from bringing samples back from the Moon’s deep impact sites to study them on Earth – something NASA is keen to try in the coming years.