In just over a decade, China’s rapidly progressing space agency, CNSA, has sent a host of spacecraft to the Moon as part of their Chang’e program, named after the Chinese goddess of the Moon. Their ambitious plans call for many more lunar missions over the next 10 years. Like most major space programs around the world, China’s ultimate goal with the Chang’e program is to lay the groundwork for establishing a permanent presence on the Moon. So, let’s step back and take a look at what they’ve done so far.

Past: Chang’e gets started

In late 2007, China launched its first Moon-exploring spacecraft, aptly named Chang’e-1. By 2009, the lunar orbiter had successfully completed its primary goal of mapping the surface to scout landing sites for future landers. In 2010, another successful orbiter named Chang’e-2 followed, and accomplished a similar set of objectives.

Encouraged by their achievements, in 2013 CSNA launched Chang’e-3, which was their first attempt to land a spacecraft on the lunar surface. By the end of the year, Chang’e-3 had done just that, making China the third country, after the Soviet Union and the United States, to softly land (as opposed to crash) on the Moon.

After touching down on the vast lava plain Mare Imbrium, Chang’e-3 achieved yet another milestone when it deployed a six-wheeled, car-sized rover on the Moon’s surface. The rover — named Yutu, which translates to “Jade Rabbit” — became the first wheeled vehicle to traverse the lunar landscape since the Soviet’s Luna 24 mission in 1976.

Chang’e-3 also came equipped with an onboard observatory called the Lunar-based Ultraviolet Telescope (LUT), which is the first long-term observatory ever deployed on the Moon. Because it has almost no obscuring atmosphere and experiences long nights, the 6-inch (15 centimeter) LUT telescope is well-suited for gazing upward and capturing images of the night sky. This helps researchers study objects ranging from variable stars to novae to the active cores of galaxies.

Thanks to power supplied by solar panels and a radioisotope heater unit, engineers think Chang’e-3 and LUT could have kept functioning a few more decades, but at the end of 2018, China powered them down in order to focus on the fourth iteration of their Chang’e program.

Present Landers: Chang’e-4 and Yutu 2

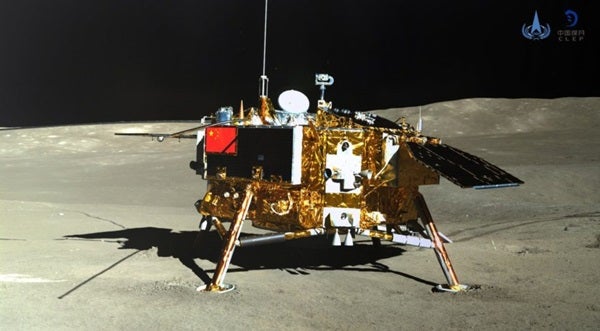

With a lander and rover designed much like Chang’e-3, the Chang’e-4 mission launched in December 2018 and arrived at the Moon just a few days into 2019. Unlike any lunar lander before it, Chang’e-4 set up shop on the far side of the Moon. Specifically, it touched down within Von Kármán Crater, which sits inside the even larger 1,600-mile-wide (2,500 km) impact crater known as the South Pole-Aitken basin.

“According to the measurements of Chang’e-4, the temperature of the shallow layer of the lunar soil on the far side of the Moon is lower than the data obtained by the U.S. Apollo mission on the near side of the Moon,” Zhang He, executive director of the Chang’e-4 mission, said to China’s state media Xinhua. “That’s probably due to the difference in lunar soil composition between the two sides of the Moon. We still need more careful analysis,” she said.

The Chang’e-4 lander also came equipped with a mini-biosphere experiment, which contained several types of seeds, fruit fly eggs, and yeast. To the delight of researchers around the world, within just a few short days of landing, Chang’e-4 returned an image of the container that showed its cotton seeds had sprouted. They continued to grow for about a week, but eventually succumbed to the freezing temperatures outside their protective capsule, dying as lunar day turned to night.

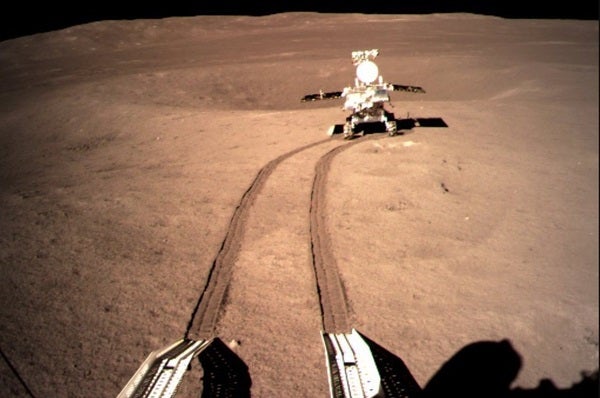

Within about 12 hours of touching down on the lunar surface, Chang’e-4 also deployed its Yutu-2 rover, which is now studying the area immediately surrounding its landing site. Equipped with a ground-penetrating radar and onboard spectrometer, Yutu-2 aims to investigate the internal structure of the Moon, as well as the composition of the lunar soil, for as long as possible. Just recently, Yutu-2 carried out an analysis of rocks found within a young, small crater tucked in the larger South Pole-Aitken Basin. These samples contained a unique blend of minerals like olivine and pyroxene, which researchers say serves as strong evidence that the Moon once had a molten mantle below its crust.

Unlike the original Yutu rover, Yutu-2 has already exceeded its expected lifetime of three lunar days (or about three Earth months). As of late April, Yutu-2 had entered its fifth lunar day and had traveled a total of about 600 feet (180 meters), more than 50 percent farther than its predecessor. And although China has largely remained tight-lipped about science results from Chang’e-4, the data collected by the lander and rover are almost guaranteed to be studied for years to come.

Present satellites: Queqiao and Longjiang

As you may expect, landing on the far side of the Moon carries its own set of unique challenges; and one of the biggest is communication. Because the entirety of the Moon sits between Chang’e-4 and Earth, it’s impossible for ground control to directly communicate with the lander. To overcome this hurdle, six months before the launch of Chang’e-4, China also launched a relay satellite named Queqiao.

Queqiao literally means “Magpie Bridge,” which is a reference to a Chinese folktale called “The Cowherd and the Weaver Girl,” in which a flock of Magpies link their wings to form a bridge across the Milky Way. By sliding the satellite into a halo orbit around the Earth-Moon L2 Lagrange point — a stable location where the gravitational pulls of the Earth and the Moon balance out — Queqiao is able to transmit data to and from anywhere on the far side’s surface. Queqiao is the first lunar relay satellite to set up shop at this location.

Although CNSA lost contact with Longjiang-1 before it entered lunar orbit (thanks to a thruster control malfunction), Longjiang-2 successfully entered lunar orbit in May 2018. Since then — except for a brief period of radio silence during the landing of Chang’e-4 — the small satellite has been snapping pictures of both the lunar surface and Earth. Based on the returned images, Longjiang-2 has verified that the lunar far side has many more craters than the Moon’s near side.

Coming up: Chang’e-5, and 6, and …

Fresh after the success of Chang’e-4, China is wasting no time with its next step on the path to a permanent lunar presence: Chang’e-5.

Scheduled for launch later this year, Chang’e-5 aims to venture to the Moon’s near side and land at Mons Rümker, a volcanic plain in Oceanus Procellarum that is packed with dozens of shield volcanos called lunar domes. Here, it will collect and return lunar samples to Earth for the first time since the 1970s. If successful, the mission will cement China as the third country to accomplish a two-way trip to the Moon and back.

Although Chang’e-5 will have a slew of scientific instruments — including a spectrometer, cameras, and a ground-penetrating radar — its primary job will be to collect about 5 pounds (2 kg) of material from more than 6 feet (2 m) below the lunar surface. It will then load these samples into an ascent vehicle that will ferry them to a lunar orbiter. The orbiter will then transfer the samples to a re-entry module designed to safely return them to Earth for further analysis.

If all goes well with Chang’e-5, China will move on to Chang’e-6, tentatively scheduled for launch around 2023. With an overall setup nearly identical to Chang’e-5, Chang’e-6 would carry out an even more ambitious sample return mission to either the Moon’s south pole or far side.

Keeping up the breakneck pace, China then plans to launch Chang’e-7 in the mid 2020s. This survey mission will utilize a lander to methodically explore the Moon’s south pole, with the primary goal of detecting water ice trapped in permanently shaded spots like the bottoms of craters. By scouting out these areas, Chang’e-7 hopes to identify ideal locations for future lunar bases.

Finally, Chang’e-8 is roughly planned for launch in the late 2020s. In addition to a lander, rover, and flying detector, Chang’e-8 will also bring a 3D-printing experiment designed to test building a structure on the lunar surface using readily available materials located nearby — a process called “in-situ resource utilization.” By doing so, China will be well on their way to accomplishing their goal of a crewed Moon landing by the 2030s, as well as their Moonshot dream of building a lunar outpost shortly thereafter.

With a handful of successful and boundary-pushing lunar missions already under its belt, China is proving to the world it can compete with the more established space superpowers when it comes to exploring the Moon. So stay tuned, because we very well could be about to enter a second space race.