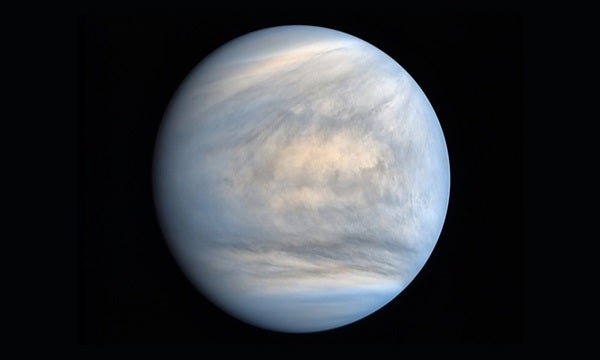

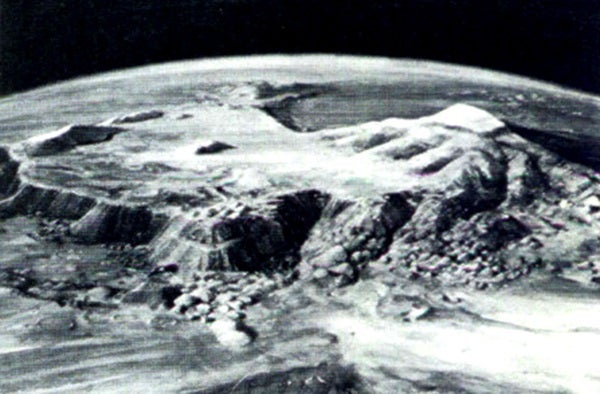

If you could peer through the 160 miles of noxious clouds driven by hurricane-force winds over Venus, you’d witness a barren landscape strewn with volcanoes, mountains and high plateaus. Scientists have long suspected that these features formed hundreds of millions of years ago. And today, the thinking went, Venus is geologically dead. But now a cascade of new research in is forcing astronomers to reconsider that idea.

Explaining Venus’ young surface

Venus is often called Earth’s twin because the neighboring planets are nearly identical in size and mass. But any comparisons end there. Venus doesn’t have a moon or a magnetic field. Its atmosphere is a stifling 100 times thicker than Earth’s. In fact, Venus’ runaway greenhouse effect leaves it with surface temperatures hot enough to melt lead — averaging around 850 degrees Fahrenheit. But as scientists take a closer look at what’s happening beneath Venus’s clouds, they’re noticing it has some geologic similarities to Earth and more action than originally thought.

“Over the last eight years, I think there’s been an increasing awareness among some people that there’s a lot of activity recorded in Venus, more than we had recognized,” said Paul Byrne, a planetary geologist at North Carolina State University in Raleigh.

Unlike other rocky bodies in the inner solar system, Venus’ surface is free of scars from asteroid impacts. Scientists have explained this young surface by suggesting some catastrophic event resurfaced the planet between 250 million and 750 million years ago. The idea was that much or all of the planet’s rigid outer layer — the lithosphere — sank into Venus’ interior and left the whole planet smooth.

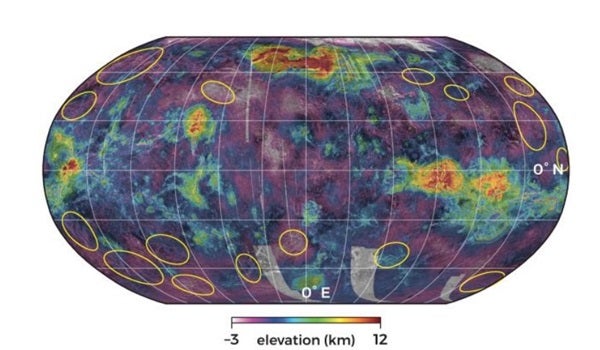

Yet new research on Venus’ looking at its center of mass, surface geochemistry, and spikes in volcanic gasses, suggest that the truth is far less cataclysmic. Instead of one large event, the research proposes Venus’ 1,600-plus volcanoes are still active – and are constantly repaving portions of the Venusian surface. Studies of the iron content of certain lava flows show they aren’t weathered, meaning they may have formed less than 250,000 years ago — recent in geological terms.

“I think everyone would agree it’s time to stop thinking that catastrophic resurfacing is the best interpretation,” said Suzanne Smrekar, a planetary geophysicist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “It’s one interpretation, but it’s not one that’s most consistent with surface geology.”

Mini-plate tectonics

The planet’s surface, in addition to the constant repaving, also seems to be on the move. Venus doesn’t have tectonic plates like Earth, but new research suggests that fragmented regions of the planet’s surface act like pack ice drifting across the ocean. It shows that Venus’ surface isn’t entirely solidified. The team of astronomers behind the new study, including Byrne, think these regions are thin parts of the lithosphere – the planet’s outer layer — that continually jostle about and get stretched and squished as a result of motion of the mantle below.

In a similar study published in 2014, scientists also discovered that one high plateau in Venus’ northern hemisphere even shows evidence of having moved an enormous distance, creating high-standing mountains. That’s comparable to the same forces causing the Himalayas to rise as the long-drifting Indian subcontinent slams into the Eurasian plate.

And while Venus’ surface is starting to be better understood, there are still many mysteries surrounding its interior that scientists say could benefit from further measurements. While no liquid water exists on Venus’ surface, scientists think there might be water locked away in the interior.

“We used to think that Venus must be dry in its interior because its surface is dry,” Smrekar said. “From these new studies about other bodies in the solar system, we realize that just because the surface is dry today, that doesn’t tell us anything about what’s going on in the interior.”

On Earth, plate tectonics serve as a way for heat and water to escape into the atmosphere, but Venus doesn’t have the same type of tectonics. While Earth has lost about half of its internal water by some estimates, Venus may have only lost a quarter, leaving it possibly still hot and steamy on the inside.

Updating the textbooks

These new insights are radically changing how scientists view Venus, both on the surface and deep below. Much of what’s currently reported about Venus in textbooks came out of NASA’s Magellan mission, which launched in 1989. So, as astronomers analyze datasets from more recent missions sent to Venus, like JAXA’s Akatsuki and ESA’s Venus Express, they’re starting to gather fresh clues about ongoing volcanism and changes to the planet’s geography. However, even that isn’t enough to get a full picture in the way some scientists would hope.

“Magellan data can only bring us so far,” Byrne said. “We absolutely need more data and missions to go back and really test these ideas and have data into the details on how the surface of Venus came to be the way it is.”

In the meantime, Byrne notes, “I think that it’s definitely time to update [textbooks].”