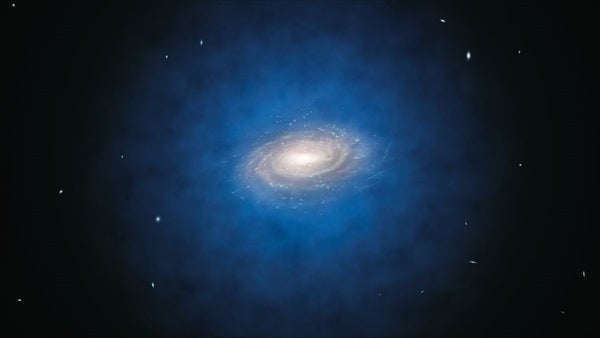

A massive clump of dark matter may have plowed through a conga line of stars streaming around the Milky Way, according to new research presented Tuesday at the 234th Meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

The research, led by

Ana Bonaca of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, reveals a curious abnormality in an otherwise uniform stream of stars orbiting in the Milky Way’s outer halo. Specifically, the researchers found an odd kink within the stream that they think was caused by a “close encounter with a massive and dense perturber,” according to the presentation’s

abstract.

Because there are no obvious culprits made of normal matter that fit the bill, the researchers believe the intervening object could be a 5 million-solar-mass blob of dark matter that ripped through the stream at over 500,000 miles (800,000 kilometers) per hour roughly half a billion years ago.

Although this theory is far from confirmed, the unique observation does open the door to the possibility of using stellar streams like this one to constrain the properties of dark matter in the Milky Way. For example, if it was truly dark matter that tore through this stellar stream, Bonaca says it would suggest dark matter is “cold,” meaning it’s heavy, relatively slow moving (non-relativistic), and effectively clumps together.

Astronomy

Astronomy magazine has teamed up with Emmy Award-winning artist Jon Lomberg to offer

Galactic Tidal Star Streams. This poster is the first and only artwork showing galactic tidal star streams, which occur as larger galaxies rip stars away from smaller ones and consume them. You can get this 16” x 20” print at

MyScienceShop.com today!

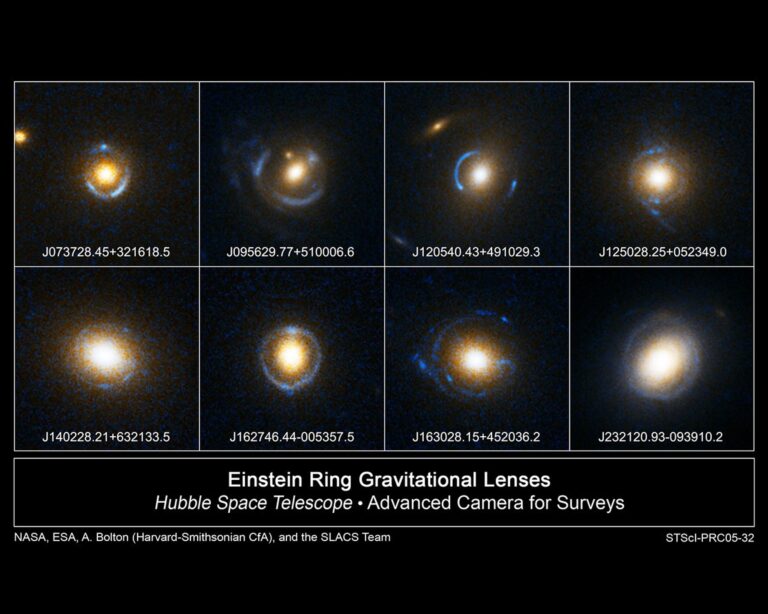

A cosmic bullet

To carry out the study, Bonaca and her team used data from the ESA’s Gaia space observatory, which has observed over a billion objects with unparalleled precision. Using this data, they mapped the positions and motions of stars in the stellar stream GD-1, which astronomers believe is the remains of a 70,000-solar-mass collection of old stars (called a globular cluster) that was shredded by past gravitational interactions with the Milky Way.

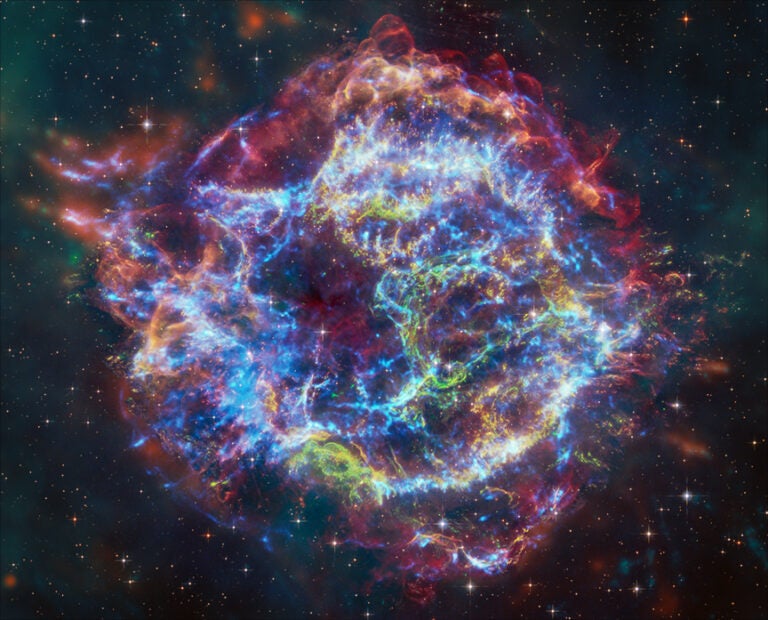

After noticing that GD-1 has an impact scar — a line of ejected stars — that indicates a past interaction, the researchers ran simulations to try to reproduce what they saw. After testing a variety of models, they found that the gravity of an object millions of times more massive than the Sun would do the trick.

The team naturally went searching for the object responsible. “Any massive and dense object orbiting in the halo could be the perturber,” Bonaca told Astronomy, “so a wandering supermassive black hole is definitely a possibility.” But so far, the team has failed to find any objects, black holes or otherwise, with the right trajectory and mass.

According to a

preprint of their paper, “Orbit integrations back in time show that the stream encounter could not have been caused by any known globular cluster or dwarf galaxy.” This led the team to conclude the “most plausible explanation” is that GD-1 had a past encounter with a clump of dark matter, like those expected to reside in the halos of galaxies.

Still hunting

Bonaca admits the current research is not conclusive. “However, if we can locate where the perturber is now, that would open new research directions, including searching for additional observational evidence [indicating it is dark matter].” Such evidence could take the form of other stars or gas clouds being jostled around by the dark matter’s gravity, or even gamma-rays associated with dark matter annihilations, which occur when two dark matter particles slam into and destroy each other, releasing a flash of energy.

Bonaca says her team recently obtained measurements of the motion of stars in the disrupted part of the stream. By mapping out where the stars are now and how they are moving, the team should be able to better calculate where the perturber could be now to locate it. That would tell them were on the sky to look for that additional evidence that the cosmic cannonball is indeed dark matter.

This animation shows how a dark, unknown mass disrupted the otherwise single-file line of stars that make up the stellar stream GD-1.

Ana Bonaca

But since there’s currently only one disrupted star stream to study, Bonaca and her team are also searching through more Gaia data to search for other examples like GD-1. In fact, they recently found

another stream called Jhelum, which likewise has a strange structure. However, Bonaca says they currently do not have a good explanation for what might have happened to this stream.

This research has been accepted June 6 for publication in the

Astrophysical Journal. An updated version of the research is expected to be published to the preprint site

arXiv.org soon.