Because these objects are hard to spot until they’re already close to the Sun, the idea is that the mission would launch without a specific target. Called Comet Interceptor, the mission would launch to a stable point in Earth orbit and then lie in wait for a fitting target.

The mission, led by ESA, will also include cooperation from the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) and NASA. ESA plans to launch the mission in 2028, along with another, previously announced mission.

A Fresh Find

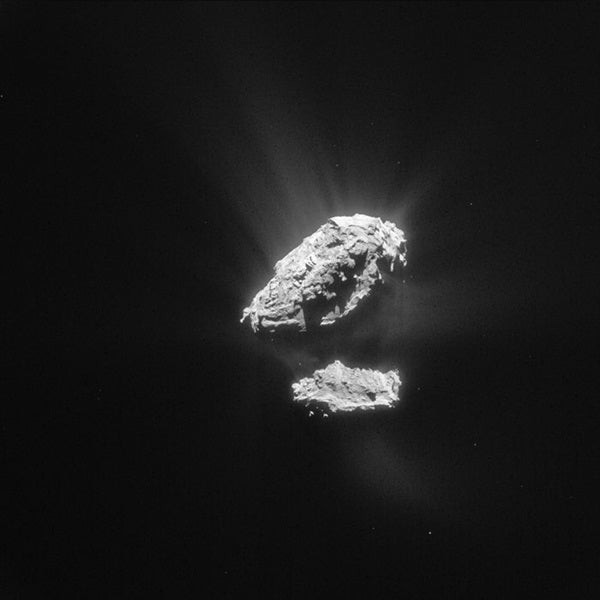

But all of the comets humans have studied so far have ventured near the Sun on their long, stretched-out orbits. That means that even if they’re primitive compared to planetary material and the weathered asteroids of the middle and inner solar system, they’ve still been altered over the eons by the Sun’s rays.

However, there are comets that have spent the whole of the solar system’s history on its fringes, and are still waiting for a close pass of Jupiter or some other object to brush their orbit and send them careening in toward the Sun for their first visit. These objects would truly tell astronomers what the chemistry of the solar system’s first building blocks were, and therefore what materials existed, and in what quantities, to build the planets and objects we see today.

Alternatively, there are objects like ‘Oumuamua that have never been part of our solar system, and whose trajectory just happens to bring them in for a close pass to the Sun. These too would be a great find, as chances to investigate close-up objects that aren’t part of our solar system are vanishingly rare.

But because comets are relatively small, faint objects, scientists don’t usually spot them until they’re only months or weeks away from the Sun, when they come closer to Earth and start to get heated by Sunlight. By that point, it’s too late to plan and launch a mission to go meet one of these objects.

A Lonely Hunter

So ESA’s idea is to launch a mission ahead of time. The spacecraft will fly to a stable orbital point between the Sun and Earth, known as Lagrange point L2, nearly 100,000 miles away. There, it can sit patiently until researchers find a suitable object.

Comet Interceptor is envisioned as one mission made of three individual spacecraft. One will serve as a communications hub, while the other two can act as dual explorers, reconnoitering the comet from multiple vantage points. They will carry multiple cameras and instruments to image the comet’s surface, measure the dust and gas around it and study how it interacts with the Sun’s magnetic fields and solar weather.

The mission is relatively small, costing only a little over $150 million. ESA plans to launch Comet Interceptor in 2028, hitching a ride with another mission called ARIEL (Atmospheric Remote-sensing Exoplanet Large-survey). But the spacecraft’s true mission timeline will depend on when the right target makes its appearance in the inner solar system, after spending billions of years hiding on its outskirts.