Although it’s relatively nearby, the far side of the Milky Way is one of the hardest parts of the observable universe to see. That means there are still outstanding questions in astronomy as to what our galactic home really looks like.

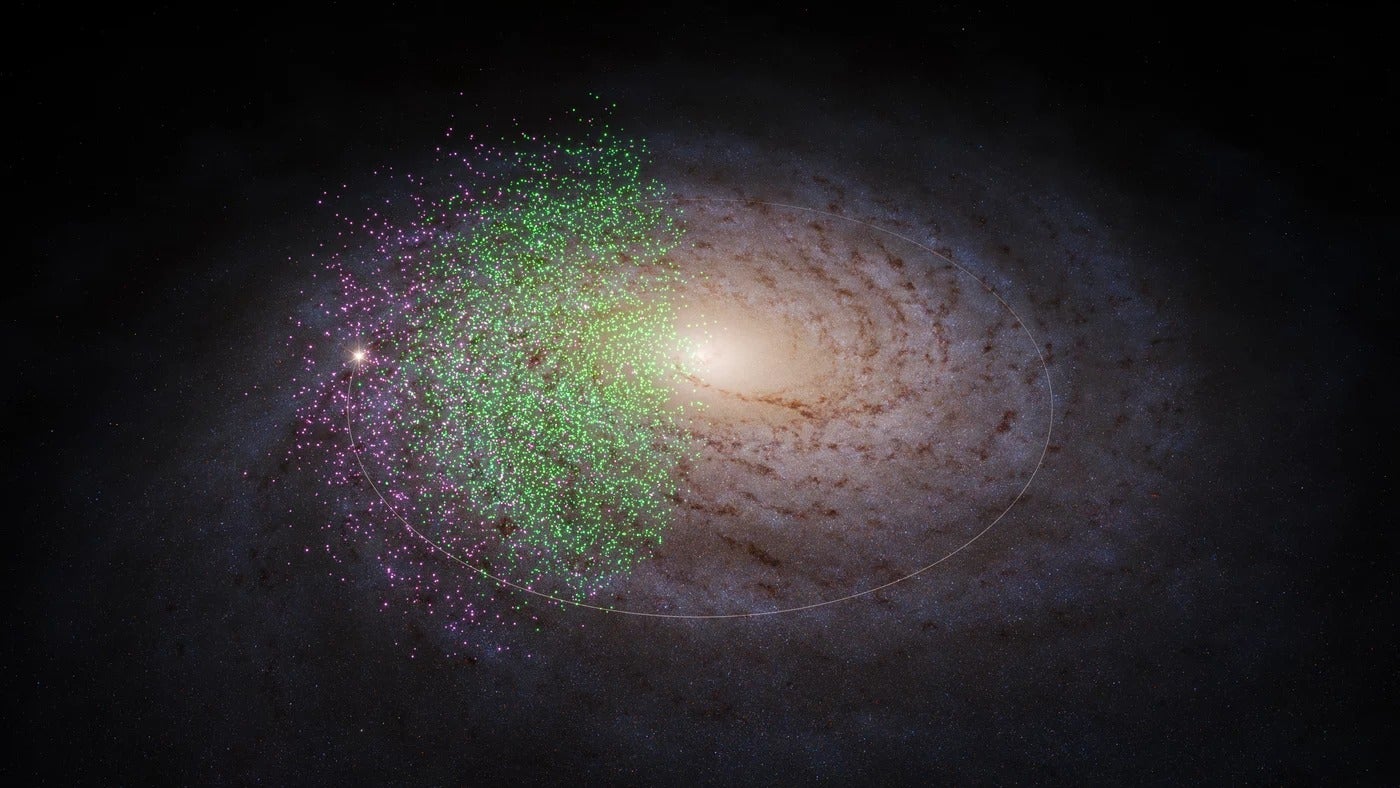

But a new study charting over 1,100 new stars on the Milky Way’s distant side provides astronomers fresh insight into its architecture, allowing us to better understand the shape of the galaxy we live in.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

The newly discovered stars are all Cepheid stars, a type of regularly pulsating star that are often used as cosmic measuring sticks. Cepheids are well-mapped on our side of the galaxy but gaps exist on the far side where they’re harder to see. This will make it easier to study longstanding questions in astronomy, for example, the degree to which the disk of our galaxy is warped.

“This sample now really closes the loop,” said István Dékány, lead author of the new study and researcher at the Center for Astronomy of Heidelberg University. “If one wants to study the warp in high detail, one now has Cepheids all around the galactic disk, and that will make the calculations much more accurate.”

The far side of the galaxy has been dubbed the Zona Galactica Incognita due to its shrouded nature, which scientists have been trying to peer through since the 1950s. Clouds of dust and stars between us and the far edge of the galaxy make it nearly impossible to get a clear picture of what’s going on there. But by looking at longer wavelengths, which cut through the dust, it’s possible to glimpse the far side.

The new study, accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal and posted online to the preprint site arXiv, used a collection of near-infrared images from the Vía Líactea ESO Public survey, which were collected over five years.

In addition to mapping the new stars’ locations, the study also measured their ages. Because the rate at which these stars’ brightness changes is correlated with their age, they are particularly useful for determining the history of star formation in the areas they inhabit. The results showed that the younger stars tended to be toward the center of the galaxy and older ones farther out. This matches observations of Cepheids on our side of the galaxy. Scientists are uncertain what is causing this pattern.

Future study of the new Cepheids could also help settle the debate of the Milky Way’s design. Our galaxy is known to be a spiral, but it’s uncertain whether the arms are well-defined (a grand design spiral) or if it is webbed with segments between the major arms.

“Mapping the far side of the galaxy will tell us if our galaxy is symmetrical, or shortened or contorted by other nearby galaxies,” said Jacques Vallée, researcher at NRC-Herzberg Astrophysics in Victoria, BC, who was not involved with the new study. However, the distances to the stars need to be more precisely measured before competing spiral galaxy models can be differentiated, Vallée noted.