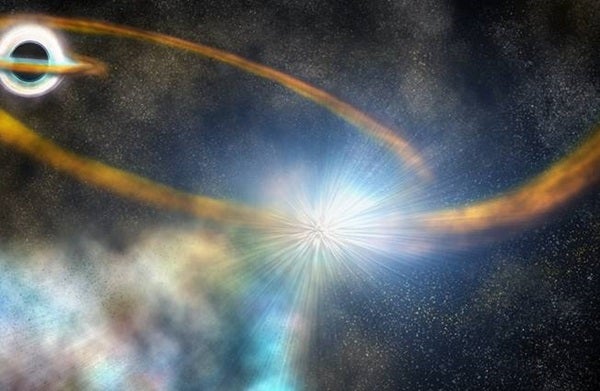

Scientists used NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) to capture the unfortunate sun getting torn apart in unprecedented detail after it passed too close to a supermassive black hole in a galaxy some 375 million light-years away.

When a black hole destroys a star, scientists call it a Tidal Disruption Event, or TDE, and this was among the most detailed such events ever seen. Astronomers hope the find will offer new insights into the exotic processes involved.

Black Hole Destruction

Back in January, an international network of telescopes dubbed the All-Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae (ASAS-SN) picked up the first signs that something was brewing in a distant galaxy. A telescope in South Africa caught the first glimpse of an object growing brighter.

Carnegie Institution for Science astronomer Tom Holoien was working at the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile that night when he saw the alert. He trained the observatory’s two ASAS-SN telescopes on the galaxy’s central black hole and notified other instruments around the world so they could do the same. The timing let astronomers collect key observations of the chemical composition and speed of the material thrown out by the destroyed star.

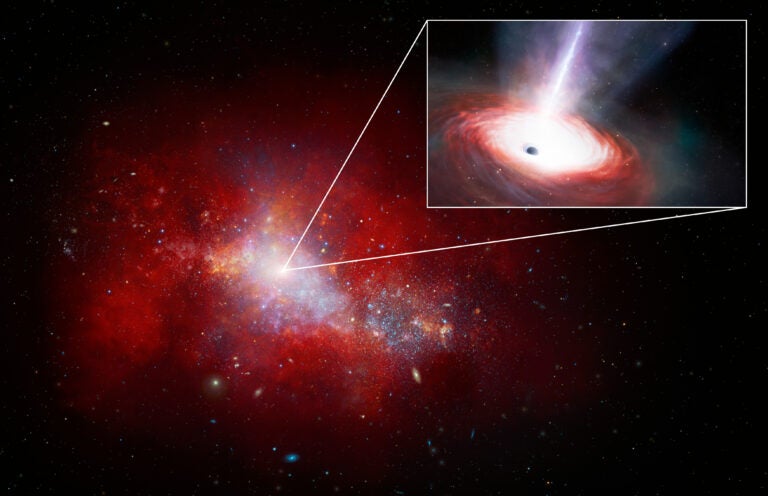

And, thanks to some good fortune, NASA’s TESS spacecraft was also already monitoring that exact same patch of sky as the event played out. That let astronomers see closer to the black hole during the process than they’d even been able to see before. The observations also confirmed that they were indeed seeing a star ripped apart by a black hole.

“TESS data let us see exactly when this destructive event, named ASASSN-19bt, started to get brighter, which we’ve never been able to do before,” Holoien said in a press statement.

And because TESS had already been studying the area for some time, scientists were able to reconstruct what happened in the weeks leading up to the star’s death. The results offer up some surprises. Astronomers used to think all tidal disruption events would look very similar.

“But it turns out that astronomers just needed the ability to make more detailed observations of them,” Ohio State researcher and study co-author Patrick Vallely said in a press release. “We have so much more to learn about how they work.”

Manholes and Black Holes

That’s been a challenge in the past. In galaxies like our Milky Way, a tidal disruption event like this one only happens about once every 10,000 to 100,000 years, researchers say. And they’re rare because it’s actually not easy for a star to find itself so close to a black hole. To get chewed up, the star must pass by the black hole at a distance about as close as our Earth is to the sun.

“Imagine that you are standing on top of a skyscraper downtown, and you drop a marble off the top, and you are trying to get it to go down a hole in a manhole cover,” Ohio State astronomer Chris Kochanek said. “It’s harder than that.”

And that makes these events much harder to spot than something like a supernova, which a galaxy may see every century or so. Just 40 tidal disruption events have ever been discovered before.

“We were very lucky with this event in that the patch of the sky where TESS is continuously observing is small, and in that this happened to be one of the brightest TDEs we’ve seen,” Vallely said.

Astronomers say the event will likely become the textbook case for other researchers to study, gleaning new insights into the extreme physics at play when a star is shredded.

The discovery was published Thursday in The Astrophysical Journal.