Astronomers have discovered a gigantic planet orbiting a puny star some 30 light-years away. And according to current theories, the planet shouldn’t exist. Dubbed GJ 3512 b, the gas giant is at least half the mass of Jupiter. But it orbits a red dwarf star that’s just one-tenth the mass of our Sun.

“Around such stars there should only be planets the size of the Earth or somewhat more massive Super-Earths,” said Christoph Mordasini of the University of Bern in a press release. “GJ 3512 b, however, is … at least one order of magnitude more massive than the planets predicted by theoretical models for such small stars.”

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

Scientists thought that gas giants like Jupiter always started their lives by developing heavy, solid cores before quickly accumulating thick, gassy atmospheres. That’s what current models predict. But because of this new planet’s unusual heft compared to its host star, the new research suggests that’s not always the case.

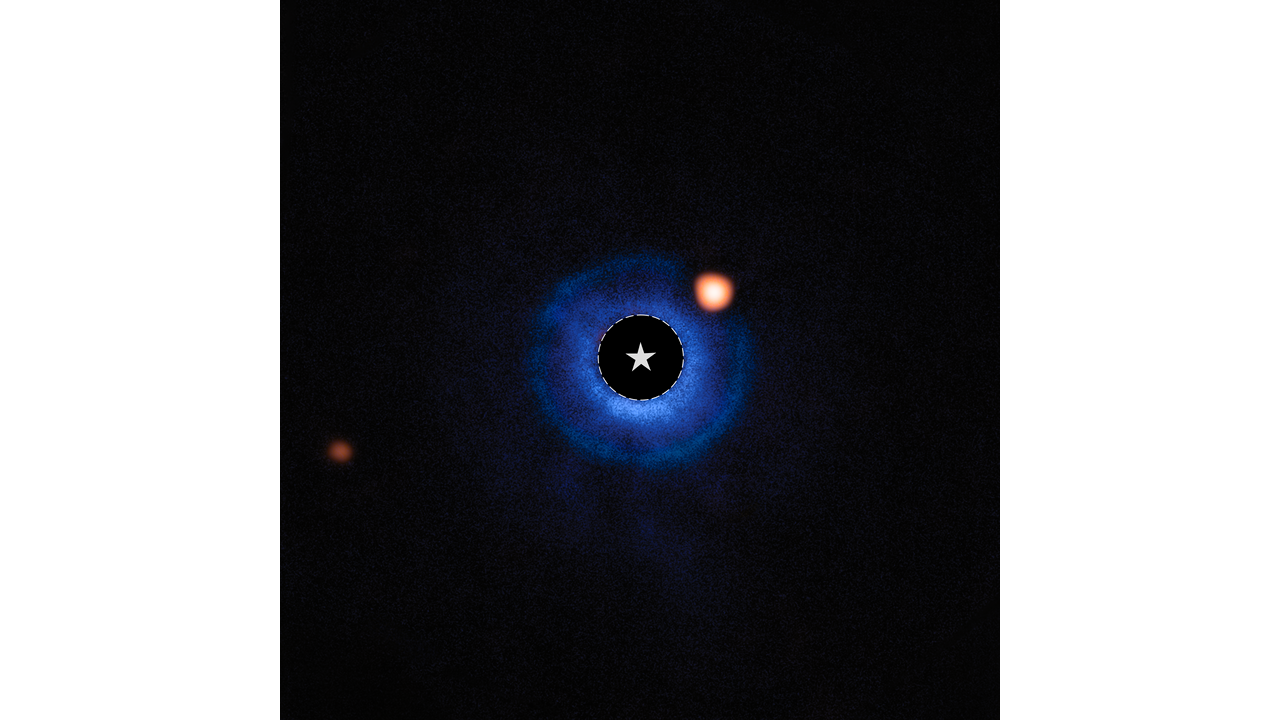

GJ 3512 and its planet(s)

The discovery is important because red dwarfs are thought to be the most common stars in the universe, accounting for roughly 75 percent of all stars. And typically, red dwarfs only have a few petite planets. This is because small stars shouldn’t have enough extra material left over from their formation to build large planets.

The planets found around red dwarfs typically range from about the mass of Earth to roughly the mass of Neptune. But they almost never approach the mass of Jupiter, like GJ 3512 b does. (For reference, Jupiter is about 300 times the mass of Earth and 20 times the mass of Neptune.)

Because GJ 3512 b is such a big fish in a little pond, the researchers say its host star shouldn’t have had enough material to form the gas giant in the first place — at least according to current models. So, simply the existence of GJ 3512 b is making researchers reconsider whether gas giant planets really must start their lives as nascent embryos of heavy particles before gobbling up copious amounts of gas (a process called core accretion).

“One way out would be a very massive disk that has the necessary building blocks in sufficient quantity,” said planet-formation expert Hubert Klahr from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA) in a press release.

The basic idea is that if the star GJ 3512 initially started its life surrounded by a particularly massive disk of both gas and dust, the gravity of the disk itself would be strong enough to trigger instabilities within it. Some regions of the disk would then directly collapse, ultimately forming large planets without undergoing the typical two-stage growth process.

In order to find the planet, researchers used the tried-and-true Doppler method. In recent years, astronomers have largely relied on the transit method for discovering exoplanets. But the Doppler method (or radial velocity method) doesn’t depend on an exoplanet passing directly in front of a star. Instead, researchers look at the star itself to see if it wobbles to-and-fro. If it does, that indicates that some other mass is in the system, forcing the star to not just spin, but also dance around the entire system’s center of mass.

This is called the gravitational disk collapse model, and so far, it’s been largely ignored when it comes to planets around red dwarfs. The major issue with this scenario is that researchers haven’t yet found examples of such oversized disks around young red dwarf stars.

But according to the study, the gravitational collapse scenario is the most logical way a planet as large as GJ 3512 b could have formed around a star so small.

And the case for gravitational collapse is made even more compelling by the fact that the astronomers also found evidence for a second large planet much farther out in the system — as well as hints that a third massive planet might have been ejected from the system long ago.

“With GJ 3512 b, we now have an extraordinary candidate for a planet that could have emerged from the instability of a disk around a star with very little mass,” said Klahr. “This find prompts us to review our models.”

The new research was published Thursday in Science.