NASA has finally taken its first small step toward sending humans back to the Moon.

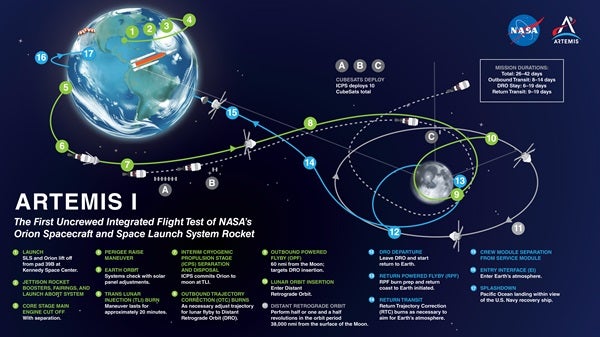

The Space Launch System (SLS) lifted off into Florida’s early morning sky today at 1:47 A.M. EST. The massive rocket lofted the uncrewed Artemis 1 mission on a 25-day flight to the Moon, carrying with it NASA’s hopes for human deep-space exploration — from the upcoming return of astronauts to the lunar surface to our eventual first steps on Mars.

Taller than the Statue of Liberty, the SLS rose into a Florida sky that hasn’t seen the likes of such an impressive launch since 1972. That’s when Apollo 17’s Saturn V took humans to the Moon for the last time. With 8.8 million pounds of thrust, the SLS is 15 percent more powerful than the Saturn V, meaning the SLS now holds the record for the most powerful rocket ever successfully launched.

Its thrust is equivalent to nearly all the train engines in the U.S. running at once — some 25,000 of them — according to NASA. Only the Soviet N-1, meant to compete with Apollo’s Saturn V, had more thrust (some 10 million pounds), but it blew up four times.

The Orion capsule atop the SLS core stage is the first human-rated deep-space capsule to fly toward the Moon in 50 years. It is intended to go farther than any such craft, reaching some 280,000 miles (450,000 kilometers) from Earth on a distant retrograde orbit.

If all goes to plan, Orion will reach the far point of its orbit 40,000 miles (64,000 km) beyond the Moon’s farside — beating the previous distance record-holder of Apollo 13. At its closest approach, Orion will be just 60 miles (100 km) above the dramatic lunar surface.

At the end of its trip, Orion’s odometer will read about 1.3 million miles (2.1 million km). When it’s done clocking those, the capsule will return to Earth at speeds up to 24,500 mph (39,400 km/h), reaching temperatures of 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit (2,700 degrees Celsius) as it reenters Earth’s atmosphere. That’s faster and hotter than any prior spacecraft.

The mission “is a test flight…It’s not without risks…We are stressing Orion beyond what it was designed for,” said Bob Cabana, NASA Associate Administrator, warning that the flight might “come home early.”

Artemis 1 begins a long lunar journey

The lift-off took place at storied Launch Pad 39B, which has hosted one Saturn V launch for Apollo 10, and four Saturn 1B missions for Skylab and Apollo-Soyuz. Prior to launch, the rocket was dramatically lit by spotlights.

The countdown and fueling went smoothly until a small core-stage hydrogen leak forced a crew of technicians to go to the pad to tighten a valve on the mobile launcher. The fix worked thanks to a three-person team that ventured into what’s called “the blast danger zone.” In another hiccup, a radar site needed to monitor the eastern launch range then went dark due to a faulty ethernet switch. Fortunately, the switch was repaired in time for the launch.

At 1:33 A.M. EST, NASA announced “no constraints” to launch, and a subsequent readiness poll at Mission Control was a go for launch. The final 10 minutes of the countdown soon resumed. Shortly before launch, plumes of water vapor were shed from the rocket like exhaled breath until just before lift-off, which is normal.

Some six seconds before the SLS’s solid rocket boosters ignited and liftoff commenced, the four core-stage liquid fuel engines started in rapid-fire succession.

At the pad, with 400,000 gallons of water gushing to suppress acoustic vibrations, the SLS let the legacy of Saturn know who the new boss was. It produced 176 decibels of sound, as loud as a continuous shotgun blast and, if you were close enough, just as deadly. The flame deflector reached a temperature of some 2,200 F (1,204 C).

The rocket was free of the Earth, apart from signals, gravity, and hopes.

The night launch meant the SLS briefly lit a false dawn. The rocket’s blinding fire was soon far more visible than the rocket itself, which leapt off Earth with the well-ordered mayhem of exhaust forming a long, thick spear of flame and smoke. The rocket’s furious plumes were visible for just over a minute before disappearing at about 42,000 feet (12.8 km).

It was as dramatic an illustration of Newton’s third law as could be dreamed of — and not just dreamed of, but precisely orchestrated. After all, the Last Quarter Moon was rising over the Space Coast as the rocket fired up and took off toward its target. Witnesses at the Space Center reported that they teared up, cheered, and felt the ground shake.

Two minutes after liftoff, the solid rocket boosters were jettisoned, appearing like massive fireworks. This was followed in short order by the release of the rocket’s service module fairing and the launch abort safety system.

The core-stage main engine cut off took place eight minutes into the flight at an altitude of about 100 miles (162 km) before quickly separating from the second stage, called the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage (ICPS).

Once in orbit, the solar wings deployed from the European Space Agency Service Module behind Orion, and a burn was conducted to raise the altitude of the craft.

Then, just over two hours into flight, occurred a phase not carried out in decades for a human-rated ship: Trans-lunar injection (TLI). The nearly 18-minute burn, using the well-proven RL-10 engine, flung Orion from 17,500 to 22,600 mph (28,000 to 36,400 km/h) on toward the Moon. The ICPS was then jettisoned.

After that, Orion’s main engine and other thrusters took over propulsion, attitude control, and navigational corrections.

Over the next several days, navigational burns will ensure Orion’s course remains crisp and true. After completing its trip around the Moon, the Orion capsule will return to Earth without the Service Module.

Stay tuned for more over the coming weeks, because the historic Artemis 1 mission is just getting started.