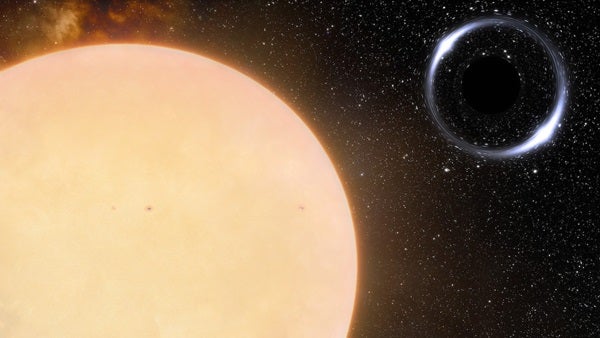

Imagine if our Sun was orbiting a black hole, perhaps spiraling into it. Admittedly, the notion that our relatively normal star could fall into such a trap sounds like the plot from a science fiction movie. Indeed, of all the black holes astronomers have previously found, none were known to threaten a Sun-like star.

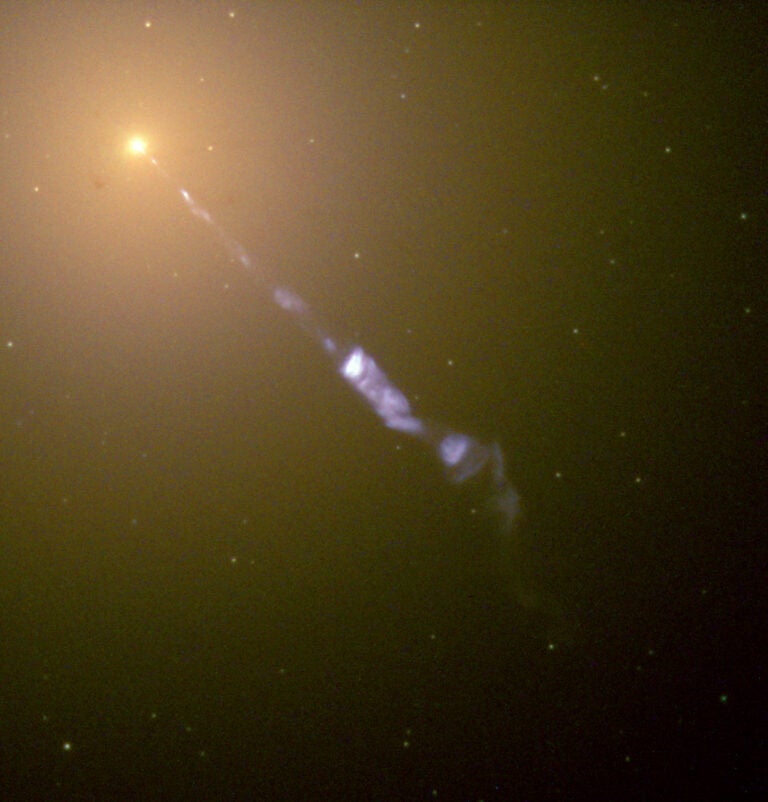

Instead, black holes tended to be tightly bound to their companion stars, stripping them of their matter, which then glows brightly as it accelerates toward its gravitational fate. That swirling accretion disk of stripped material is why black holes are bright sources of X-rays — and it’ how astronomers usually spot black holes in the first place.

But astronomers have long thought there could be a more insidious population of black hole binary systems that do not glow brightly, and so remain hidden. And if these furtive black holes are out there, then the latest generation of orbiting observatories might be able to spot them.

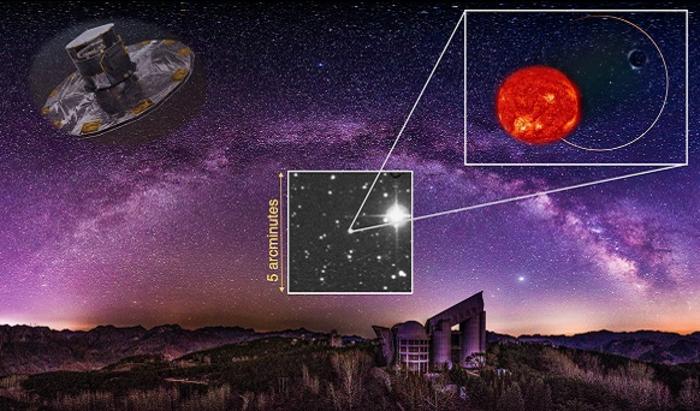

Now, Kareem El-Badry at the Harvard & Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge and others say they have discovered the first example of such a covert black hole within data gathered by the Gaia spacecraft.

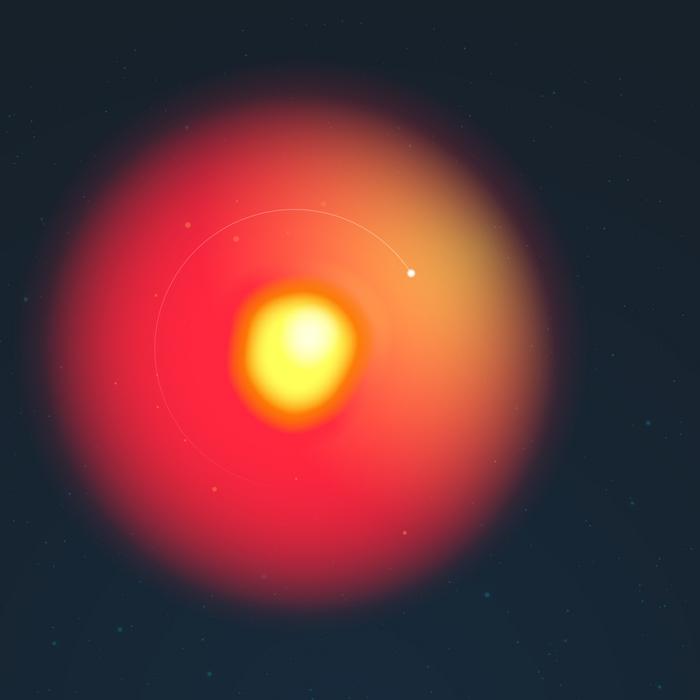

This strange system, called Gaia BH1, consists of a Sun-like star orbiting a tiny, massive object, which El-Badry and his colleagues say is black hole. If confirmed, this black hole would be the closest known black hole to Earth.

The new observations suggests black hole systems hosting seemingly ordinary stars are likely much more common than originally thought.

3D Map of the Milky Way

The Gaia spacecraft is currently measuring the positions and distances to more than 1 billion astronomical objects in our galaxy. In this way, it is assembling the most detailed 3D map of the Milky Way ever made.

As Gaia moves in its orbit around the Sun, it measures the apparent change of a celestial object’s position against the background sky, called its parallax. With a rather straightforward calculation, astronomers can then determine exactly how far away that object is located.

But from time to time, Gaia comes across objects moving in different ways, usually because they are orbiting another object. And earlier this year, El-Badry and his team found such an example in the latest Gaia dataset.

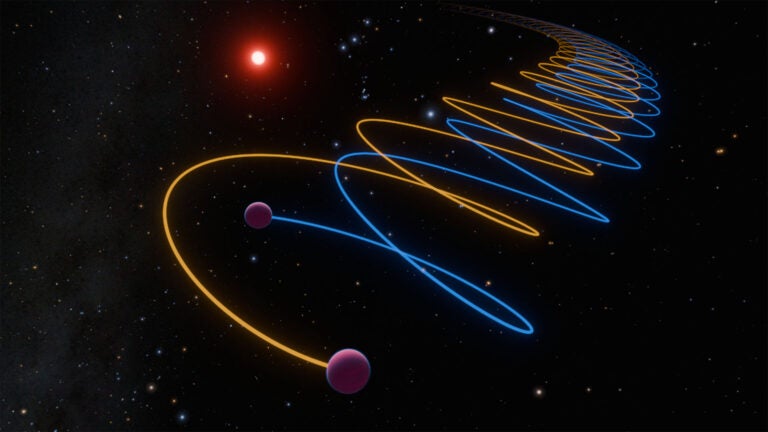

The object in question is an ordinary star about the same size, mass, and temperature as our Sun, but it resides some 1,600 light-years away in the constellation Ophiuchus the Serpent-bearer. The one strange feature about this star is its cartwheeling motion, which the researchers say is a clear indication that it must be orbiting an unseen companion every 186 days.

El-Badry and his team set out to characterize the nature of this companion. Based on a detailed series of further ground-based observations, the researchers say the suspected black-hole companion is not visible at any wavelengths. Given this motion, the Sun-like companion must have a mass about 10 times that of the Sun.

That’s too massive for the unseen object to be neutron star. And if the object were an ordinary star, it would be 500 times more luminous than its Sun-like companion. The fact that the central object remains invisible leaves only one conclusion. “We find no plausible astrophysical scenario that can explain the orbit and does not involve a black hole,” they say.

If confirmed, the interesting discovery is set to rewrite our understanding of both the nature and ubiquity of black holes. Until now, the nearest black hole to Earth was about three times farther away.

The existence of Gaia BH1 so close to Earth suggests that systems of this kind must be common. “Its discovery suggests the existence of a sizable population of dormant black holes in binaries,” write the authors in their paper, which was published Nov. 2 in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Formation puzzle

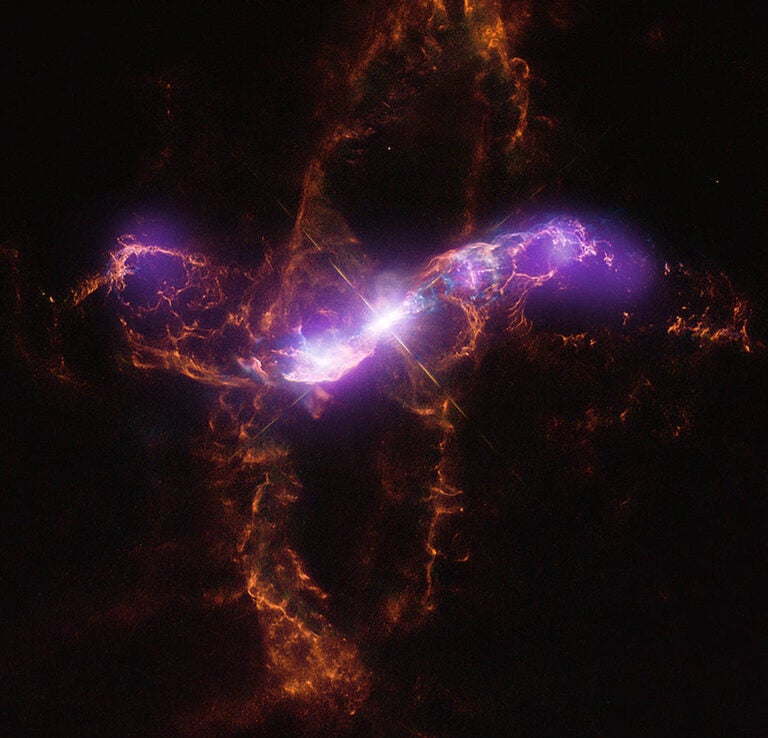

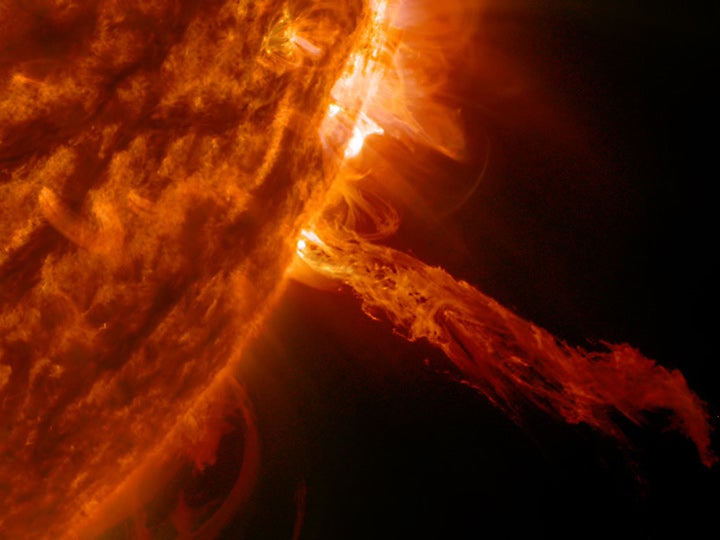

Gaia BH1 is something of a puzzle: El-Badry and his team are still scratching their heads over how it came to exist at all. The problem is that most black holes form from huge supernovae explosions that occur when massive stars die.

The researchers say the progenitor of Gaia BH1 must have been a supergiant star with a much larger radius than the current separation of the binary system. But a Sun-like star could not have survived in these circumstances during or after a supernova, so Gaia BH1 must have formed in another way. Exactly how, however, is not yet clear.

To better understand the strange system Gaia BH1, astronomers need to find other examples of hidden black holes. Fortunately, they may not have to wait long. El-Badry and his team are optimistic that “Future Gaia releases will likely facilitate the discovery of dozens more.”

Ref: A Sun-Like Star Orbiting a Black Hole: arxiv.org/abs/2209.06833