When famed Star Trek actor William Shatner embarked on a space tourism flight last year, the view brought him to tears. He later described crying while looking back at Earth, as well as a profound sense of grief — as if he had just learned about the death of a loved one.

Scientists call this feeling the “overview effect.” It happens to astronauts when they look back at Earth and feel an overwhelming connection with the planet and its people.

What a space traveler sees, of course, is all dependent on how high they fly. Whereas Shatner and other space tourists soared to 62 miles (100 kilometers) above sea level, astronauts in the International Space Station orbit around 260 miles (420 km) above. And the few who make it all the way to the Moon venture more than 226,000 miles (364,000 km) beyond Earth’s surface.

In recent years, astronauts like Tim Peake from the U.K. and Chris Hadfield of Canada have shared their experiences on social media via photographs and descriptions of the view. Their insight is helping those of us below understand what is visible from space.

Space sights

When a passenger looks out the window of an airplane, they are likely flying around 7 to 8 miles (11 to 13 km) above sea level. That puts them in the stratosphere, the second layer of our atmosphere. On clear days, passengers can see dams, bridges, monuments and other human-made structures.

The next atmospheric layer, the mesosphere, ranges from 31 to 50 miles (50 to 80 km) above sea level and is the highest layer where a cloud can form. The fourth layer, the thermosphere, ranges from 50 to 440 miles (80 to 710 km) above sea level. The thermosphere contains the point that most international space programs consider the start of space — the Kármán Line — at 62 miles (100 km) above sea level.

The ISS orbits in the thermosphere, some 260 miles (420 km) above Earth. Astronauts in the space station have described how it rotates around Earth every 92 minutes; because of this, the view is always changing. From the ISS, astronauts can identify rivers snaking through cities or forests, shining city lights, and farm fields that resemble patchwork quilts from high above.

Astronauts on the ISS have also reportedly seen deforestation in places like Madagascar, evident from the red soil that spills into the ocean. They can even spot phytoplankton blooms that discolor water, and swirling hurricanes. With a powerful camera lens, astronauts can zoom in on cities or spy human-made structures like the Egyptian pyramids; but even then, the ISS rotates so quickly that they only have a moment to snap a picture.

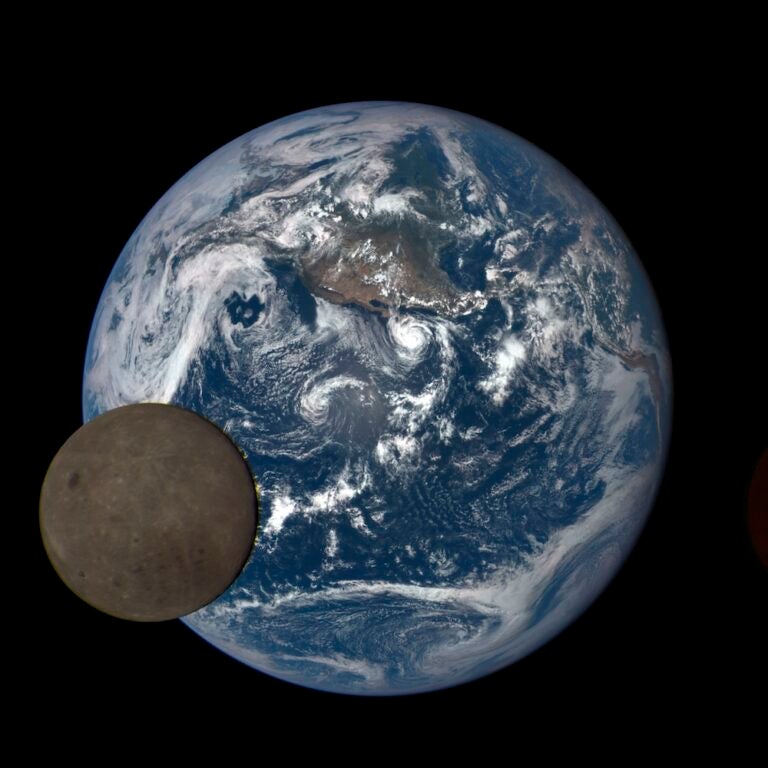

If those aboard the ISS can’t discern the pyramids or glimpse the Great Wall of China without a camera, you may be wondering what astronauts on the Moon see when they look back at our blue marble.

Moon marvels

Astronaut Neil Armstrong debunked the myth that human-made structures could be viewed from the Moon. In an oral history with NASA, he said he could make out only continents — particularly Greenland, because it was a white shape against a sea of blue. Africa was also visible, and he saw a reflection on water that he thought might have been Lake Chad.

Despite Armstrong’s first-hand observations, the claim that structures like the pyramids or Great Wall are visible from the Moon has persisted through the years. Armstrong even double-checked with other astronauts, including those on the ISS. All agreed they could not see such objects from space without a magnifying device.

Color contrast is a key factor in whether something can be viewed from space. Dark rivers that run through light-colored terrain, for example, are easy to identify from the ISS. But the Great Wall of China is a similar color to the land around it, making it difficult to see from high above even with camera equipment.

Although the Great Wall impresses people on the ground, many astronauts describe lights as the most dazzling vision from space. Astronaut Jeffery Hoffman, for example, flew five space flights between 1985 and 1996, including missions to service satellites and telescopes. From hundreds of miles in the air, Hoffman said, it only took 30 minutes to orbit the Pacific Ocean; when their shuttle approached the West Coast, the city lights that broke the darkness mesmerized the crew.

To Hoffman, the lights on the Las Vegas Strip were so “ridiculously bright” that he could see them without any equipment. From his perspective, in fact, looking down at the twinkling city was similar to being on Earth and looking up at the starry sky. “No matter where you look,” he said, “you can see the city lights below you and the stars above you.”