Key Takeaways:

Another year, another trip around the Sun!

I’ve already made more of those trips than I care to recount. But even so, I’m just as entranced now by how our planet looks from space as I was more than a half century ago. That was when I first saw this:

It’s the iconic “Earthrise” photo. Of course, this isn’t one of 2022’s images of Earth from space that I’m showcasing below. But I thought I should start with it — for context. The famous photo was taken in 1968 by astronaut William Anders as he and his two crewmates orbited the Moon during the Apollo 8 mission.

If it looks different than other versions you may have seen, it’s because the photo is usually presented on its side, making the Moon’s horizon horizontal. The version above is different. It’s a scan of the original Ektachrome transparency — film sprockets and all — in the orientation Anders used when he shot it.

Nature photographer Galen Rowell described this image as “the most influential environmental photograph ever taken,” and it has even been credited as “one of the most important photographs taken by anyone ever.”

That’s because it was one of the first images to show us what our planet looked like from very far away in space. And as Anders himself put it: “The view points out the beauty of Earth, and its fragility. It helped kick start the environmental movement. That little atmospheric thing you and I enjoy is nothing more than the skin on an apple.”

Today, seeing Earth from space is no longer novel. Yet technological innovation continues to make remote sensing imagery compelling, perhaps more so now than ever before. And not just because the images can be stunningly beautiful. As with the Earthrise photo, they can help remind us that unless we exercise care, we can seriously disrupt the life support systems of our home planet.

With that in mind, I invite you to check out the images below — some of my favorites from 2022. I sorted through multiple sources of remote sensing imagery to select these 10 particularly compelling images from the year now gone by.

Highlights of 2022

Let’s start with the photograph above. It was taken by a crew member aboard the International Space Station while orbiting more than 250 miles (400 kilometers) above the South Pacific Ocean. The oblique view features Earth’s horizon, known as the limb. It enables us to see layer upon layer of atmosphere, along with the waning-gibbous Moon shining through the thinnest layers. (The photograph was first featured by NASA’s Earth Observatory in their “Image of the Day” feature. For a full-size version, check out their story, “An Atmosphere of Exploration.”)

Oblique views of Earth as seen from space can be particularly dramatic, as this next image also demonstrates:

This sprawling cyclone is Hurricane Ian, just as its eye was making landfall near Cayo Costa, Florida on Sept. 28, 2022. Born of a tropical wave over the west coast of Africa, the storm spun up rapidly into a hurricane that first thrashed Cuba before blasting ashore in Florida. With maximum sustained winds at landfall of 150 mph, Ian pushed up inundating storm surges that caused enormous devastation along the state’s Gulf coast.

Ian’s portrait at landfall seen above is called a “sandwich’ satellite product. It combines light gathered in the visible and infrared portions of the electromagnetic spectrum, providing meteorologists with valuable information for analyzing the evolution of storms. (Note that this is a screenshot from an animation featured by the Satellite Liaison Blog. I’ve done a little processing to help clarify features of the storm.)

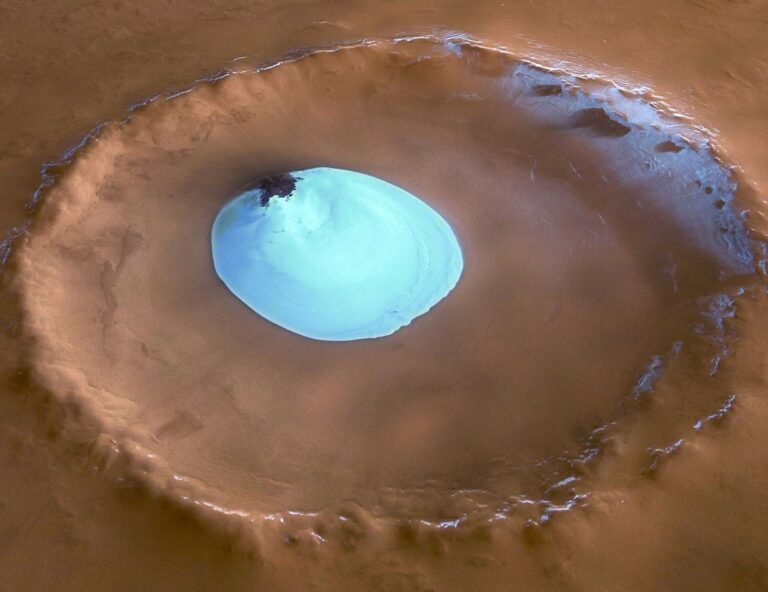

As Ian was churning toward Florida, the Landsat 8 satellite was in an ideal position to view it — as this dramatic closeup of the storm’s eye three hours before landfall shows.

The turquoise waters of the Gulf of Mexico peak through the relatively fair weather at the storm’s center, which is surrounded by a towering ring of powerful thunderstorms that make up Ian’s eyewall. (For a clickable, full-sized version of the image featuring amazing detail, check it out here at NASA’s Landsat Image Gallery.)

After landfall, Ian crossed Florida, headed out over the Atlantic, and finally crashed ashore again, this time in South Carolina. Ultimately, the storm was responsible for an estimated $50 billion to $65 billion in damages. For the United States, it was the second-costliest insured loss on record, after 2005’s Hurricane Katrina, according to reinsurer Swiss Re.

A different kind of storm

The effects of a storm of a very different kind are visible in this image (a screenshot from an animation) acquired by the GOES-16 satellite. Consisting of image data in the visible and infrared portions of the spectrum, it highlights bands of fresh snowfall being blown by strong winds accompanying the brutal Arctic outbreak of late December across a broad swath of the U.S. mid-section. The bands show up as long, gold-colored strands. Within the plumes of blowing snow, visibility was reduced to less than a half mile.

I chose this image over others that zoom in more closely on the bands of snow because, to my eye at least, it looks a bit like abstract art. Call it Earth art, or “eARTh…” To appreciate this even more fully, check out this post at the Satellite Liaison Blog, where you’ll find the animation from which I took the screenshot, along with other imagery.

The after-effects of another winter storm are seen in this NOAA-20 satellite image. It shows a swath of snowfall left by the storm across the midwestern United States.

Although the black and white rendering may not be as immediately captivating as a colorful, art-like, remote-sensing image, for me it’s just as dazzling. That’s because the satellite was able to see the swath of snow at night, with just the faint illumination of moonlight to reveal its presence — from 22,000 miles (35,000 km) away.

Seeing in the night from space is made possible by a special sensor aboard the NOAA-20 satellite called the “Day/Night Band.” It’s designed to capture relatively faint light from natural and artificial sources, such as city lights, ships, fires, flaring from energy operations, and lightning — as well as features illuminated by moonlight.

In the image, the winter storm track, as revealed by the swath of snow, culminates in the glowing metropolitan area of Chicago along Lake Michigan. Lights from other cities, and roads linking them, also stand out, as do lake-effect clouds over the Great Lakes.

This image was originally published by the CIMSS Satellite Blog, as part of their own 2022 highlights post. Click here to see all of those marvelous images. Over the years, they’ve graciously let me use many of their satellite images and animations, and I’m very grateful for that.

In the next installment of this two-part series, I’ll include another example of dramatic nighttime imagery made possible by the Day/Night Band sensor, along with more “eARTh,” and imagery featuring an erupting volcano, wildfire, and evidence of drought in the southwestern United States.

With its intricate patterning, and starkly contrasting bold colors, this image struck me as a beautiful example of “eARTh.” At first glance, it may seem like a false-color satellite image. But it’s actually a photograph taken by a crew member aboard the International Space Station on Aug. 1, 2022. The image shows Mexico’s wetlands of Adair Bay (also known as Bahia Adair), which mark the transition between the Great Altar Desert, seen in the upper portion of the photo, and the brilliant turquoise waters of the Gulf of California.

The wetlands provide the perfect environment for mangrove trees and shrubs, as well as other salt-tolerant vegetation, helping to create a rich coastal environment. The waterways that course through the wetlands have a beautiful fractal-like appearance. (For the full-size, clickable version of this image, see this post at NASA’s Earth Observatory.)

Erupting volcano seen from space

Some of my favorite images of 2022 — and of all time — come from remote sensing whiz Pierre Markuse, who created the next image using data from the Sentinel-2 satellite:

Combining visible and infrared light, it shows Russia’s 10,771-foot-high Shiveluch volcano erupting on Dec. 3, 2022. Shiveluch is is one of largest and most active volcanic structures on Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula, with at least 60 large eruptions during the Holocene Epoch (the last 11,700 years of Earth’s history). For the original, full-sized image, check it out here.

Here’s a second stunning image from Markuse, of another fiery subject:

Among many images from his Flickr photostream, this one caught my eye because of its beautiful coloring, and the intricate patterning of the mountains and waterways. But the subject is quite serious: This is an infrared view of parts of the The Hermits Peak-Calf Canyon Fire in New Mexico, acquired by the Sentinel-2 satellite on May 13, 2022. At this point, two fires that had begun separately in April were being managed as one giant wildfire.

In the image, which is about 150 miles (240 km) wide, areas of active burning show up in orange and yellow. Rusty-red tones reveal large swaths of land that had already burned. Much more scorched land lies outside the frame.

By the time the fire was fully contained on Aug. 21, 534 square miles (380 square kilometers) had burned — an area larger than the City of Los Angeles. This made it the largest wildfire in New Mexico’s history. It was also the most damaging, with at least 903 structures destroyed.

On the same day that Pierre Markuse published this false-color image, I used Sentinel-2 imagery to create a visualization simulating an overflight of the fire. Here it is:

The Colorado River Basin

Drought conditions played a major role in the spread of the Hermits Peak-Calf Canyon Fire. On a much broader scale, those conditions — described as a megadrought by scientists — had left the Colorado River Basin in crisis.

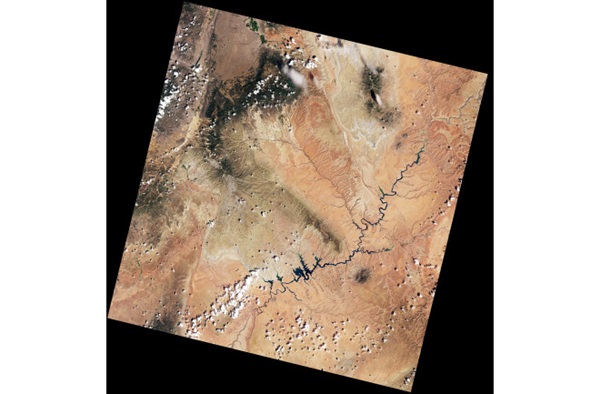

Images of the region from space often are quite beautiful, as the next one, from NASA’s Earth Observatory site, demonstrates:

This is how the Landsat-9 satellite saw Lake Powell and a large portion of the surrounding Colorado River Basin on Aug. 6, 2022. Diagonally, the image is about 120 miles (190 km) across. The lake — the second largest reservoir in the United States — is the dark, sinuous feature that contrasts dramatically with the multi-hued and intricately patterned desert landscape.

By itself, however, the image doesn’t easily reveal the increasingly dire situation facing 40 million people who depend on water from the Colorado River Basin. So I paired it with a comparison image acquired by Landsat-8 on Aug. 16, 2017 to create this before-and-after animation:

Between the time that the two images were acquired, the elevation of Lake Powell, impounded by the Glen Canyon Dam, dropped nearly 100 feet, reaching its lowest level since it was filled in the mid-1960s. As this has happened, the reservoir has shriveled so much that it is easily seen from space — as the animation shows.

Downstream from Lake Powell is Lake Mead, the largest U.S. reservoir, and it too stands at a record low level. The situation has gotten so bad that it is approaching what Bob Martin, deputy power manager at Glen Canyon Dam, has described as “a complete doomsday scenario.”

Pushed now to the brink, policy-makers and water managers may finally figure out a way to set things in the Colorado River Basin on more sustainable course.

On a happier note…

I’ll leave you with this:

As I previously mentioned, a black and white satellite image like this may not seem as immediately captivating as a colorful one. But for me, at least, it’s just as dazzling.

This one was acquired by the Suomi NPP satellite on Feb. 4, 2022. It reveals swirling streams and eddies of light over central Canada and Hudson Bay — the aurora borealis, or northern lights.

The nighttime view was made possible by a special sensor aboard the satellite called the “Day-Night Band,” which measures nighttime light emissions and reflections, including city lights, reflected moonlight, ships at sea — and the glow from the northern lights. (For an explanation of the aurora borealis, check out my post from November featuring a similar image: “The View From Space as the Northern Lights Set the Sky Afire Above Canada.”)

I’m hoping that you’ve found some inspiration from the images I’ve showcased here. I also hope they’ve conveyed an idea articulated in a particularly beautiful way by author Jeffrey Kluger in his book, “Apollo 8: The Thrilling Story of the First Mission to the Moon.”

Writing about the Earthrise image taken by William Anders, Kluger noted that it “would eventually move people to appreciate that worlds — like glass — do break and that the particular world in the picture perhaps needed to be cared for more gently than humans ever had before.”