The half-asteroid, half-comet dubbed 10199 Chariklo, located beyond Saturn, is a ball of rock and ice about 170 miles (270 kilometers) across. Due to its rather diminutive size, astronomers were surprised in 2013 when they detected rings around it — something they only expected to find around giant planets.

Now, Chariklo’s rings have been observed by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), revealing strong evidence of water-ice in the system. The new observations are also helping scientists learn more about why such a small object like Chariklo has rings at all.

James Webb targets a centaur

On Oct. 18, 2022, researchers used JWST to observe the rings around Chariklo, which belongs to a mysterious class of solar system objects called centaurs. These hybrid objects skirt the line between asteroid and comet, typically behaving like comets while having surfaces that more closely resemble those of asteroids.

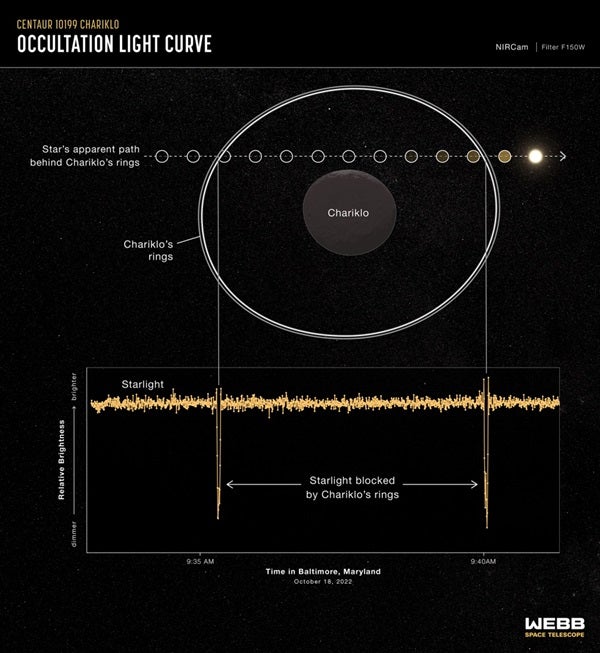

Researchers were particularly interested in how Chariklo’s rings absorbed light from a background star passing behind it — much the same method used to discover the rings in the first place.

Observing this particular event, called an occultation, was only possible because JWST can see much fainter stars than any other telescope, says Pablo Santos-Sanz, an astronomer at the Andalusian Institute of Astrophysics in Spain and one of the project’s leaders.

“This was unique,” he tells Astronomy. “It allowed us to characterize these rings as never before.”

How Chariklo got its rings

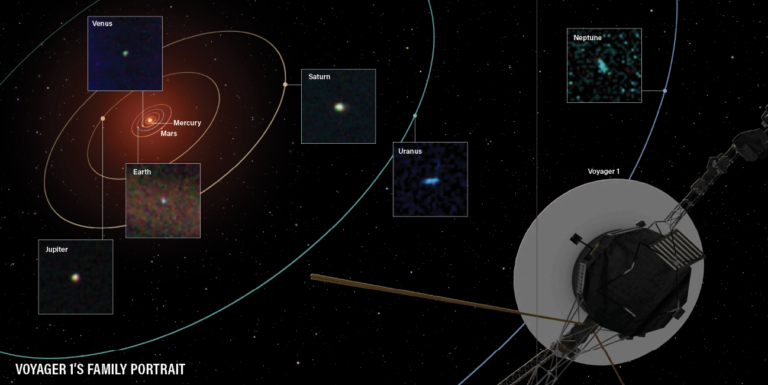

Like other centaurs, Chariklo is a Kuiper Belt object that was dislodged from its original extreme orbit on the edge of the solar system by the gravity of Neptune. As a result, it now orbits the Sun between Saturn and Uranus.

Eventually, Chariklo will likely be swallowed up by Jupiter, especially if it gets nudged closer to the gas giant. But if it does somehow make it to the inner solar system, then it is likely destined to behave more like a full-fledged comet.

Astronomers discovered Chariklo back in 1997. But it wasn’t until a different star passed behind the centaur in 2013 that they noticed a “double blink” shortly before and after the occultation. This indicated that Chariklo hosts rings of material around it, a bit like a tiny saturnian system.

Measurements of the unexpected dips in brightness suggested Chariklo has two rings that orbit about 155 miles (250 km) above its frozen surface.

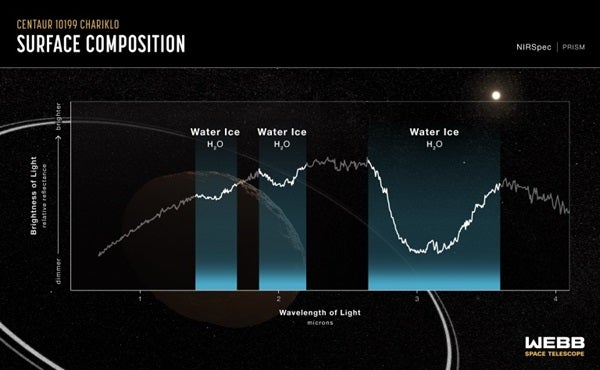

Santos-Sanz thinks these rings are made up of tiny pieces of the centaur, mostly water ice, that have accumulated in a region with “3:1 spin-orbit resonance” — meaning Chariklo rotates one time for every three times the material orbits it.

“Particles from the surface of Chariklo can escape the object after impacts from other bodies or meteorites,” he says. “These particles… end up in this special stability region and then form the rings.”

Planning for an occultation

To capture the new observations, Santos-Sanz and his colleagues made weekly predictions of Chariklo’s orbit and updated the position of JSWT accordingly. (The space telescope carries out station-keeping maneuvers to stay at the second Lagrange point [L2], where the Earth shades it from the Sun.)

One of Santos-Sanz colleagues is astronomer Filipe Braga Ribas of the Federal University of Technology Paraná in Brazil, who led the observations that discovered Chariklo’s rings in 2013 using ground-based telescopes in South America.

The latest observations were especially difficult, Braga Ribas tells Astronomy, because JWST was often moving.

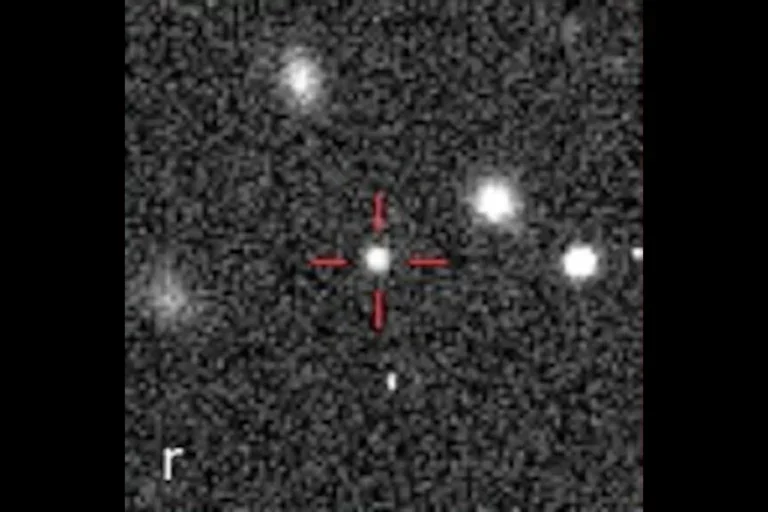

Initial predictions in August indicated both Chariklo and it rings would occult Gaia DR3 6873519665992128512, which is a star in the direction of Serpens Cauda (“The Snake’s Tail”) that is much too faint to see without a powerful telescope.

But JWST had changed position by the time it carried out its observations in October. That meant only Chariklo’s rings actually occulted the star.

“We missed the main body, but the details on the detection of the rings will allow a great step forward on the knowledge of the system,” Braga Ribas says.

As well as precisely measuring the width of Chariklo’s rings, the light curves from the JWST’s Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) reveal details like their thickness and the sizes and colors of the ring particles. The astronomers also used the JWST’s Near-infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) to scrutinize the filtered starlight as the star passed behind the centaur’s rings.

Researchers identified three absorption bands of crystalline water-ice. Though past research hinted that water-ice might exist somewhere in the Chariklo system, this is the first clear detection of such ice. The fact this ice is present suggests microcollisions continuously expose new surface materials or possibly trigger the crystallization.

“The successful occultation prediction and observation of this system from a moving platform is impressive,” Amanda Sickafoose of the Planetary Science Institute, who was not involved in the research, tells Astronomy.

Sickafoose has previously studied another centaur, 2060 Chiron, which is thought (but not confirmed) to have similar rings. She finds it interesting that the light curve from Chariklo’s outer ring suggests it is optically thinner than its inner ring, which could have implications for how each ring evolved.

Because Chariklo is one of the few small bodies in the solar system with rings, “the information gained from JWST will greatly increase our knowledge of that specific system, Sickafoose says, “as well as contribute to our overall knowledge of these newly-discovered dynamical systems.”