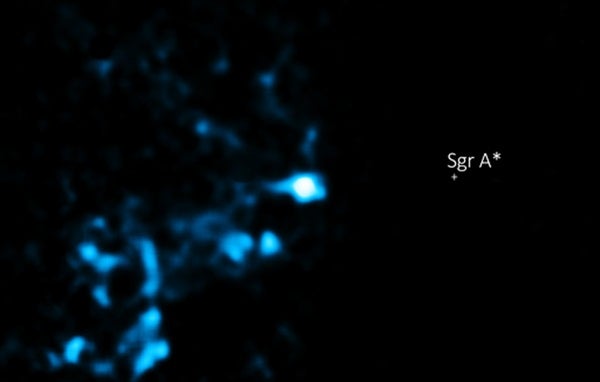

This discovery comes from a new study of rapid variations in the X-ray emission from gas clouds surrounding the supermassive black hole Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*). The scientists show that the most probable interpretation of these variations is that they are caused by light echoes.

The echoes from Sgr A* were likely produced when large clumps of material, possibly from a disrupted star or planet, fell into the black hole. Some of the X-rays produced by these episodes then bounced off gas clouds about 30–100 light-years away from the black hole, similar to how the sound from a person’s voice can bounce off canyon walls. Just as echoes of sound reverberate long after the original noise was created, so too do light echoes in space replay the original event.

While researchers have seen light echoes from Sgr A* before in X-rays by Chandra and other observatories, this is the first time that they’ve found evidence for two distinct outbursts within a single set of data.

More than just a cosmic parlor trick, light echoes provide astronomers with an opportunity to piece together what objects like Sgr A* were doing long before there were X-ray telescopes to observe them. The X-ray echoes suggest that the area close to Sgr A* was at least a million times brighter within the past few hundred years. X-rays from the outbursts — as viewed in Earth’s timeframe — that followed a straight path would have arrived at Earth at that time. However, the reflected X-rays in the light echoes took a longer path as they bounced off the gas clouds and only reached Chandra in the last few years.

The X-ray emission shown here is from a process called fluorescence. X-rays have bombarded iron atoms in these clouds, knocking out electrons close to the nucleus and causing electrons farther out to fill the hole, emitting X-rays in the process. Other types of X-ray emission exist in this region but are not shown here, explaining the dark areas.

This is the first time that astronomers have seen both increasing and decreasing X-ray emission in the same structures. Because the change in X-rays lasts for only two years in one region and over 10 years in others, this new study indicates that at least two separate outbursts were responsible for the light echoes observed from Sgr A*.

There are several possible causes of the outbursts: a short-lived jet produced by the partial disruption of a star by Sgr A*; the ripping apart of a planet by Sgr A*; the collection by Sgr A* of debris from close encounters between two stars; and an increase in the consumption of material by Sgr A* because of clumps in the gas ejected by massive stars orbiting Sgr A*. Further studies of the variations are needed to decide among these options.

The researchers also examined the possibility that a magnetar — a neutron star with a strong magnetic field – recently discovered near Sgr A* might be responsible for these variations. However, this would require an outburst that is much brighter than the brightest magnetar outburst ever observed.