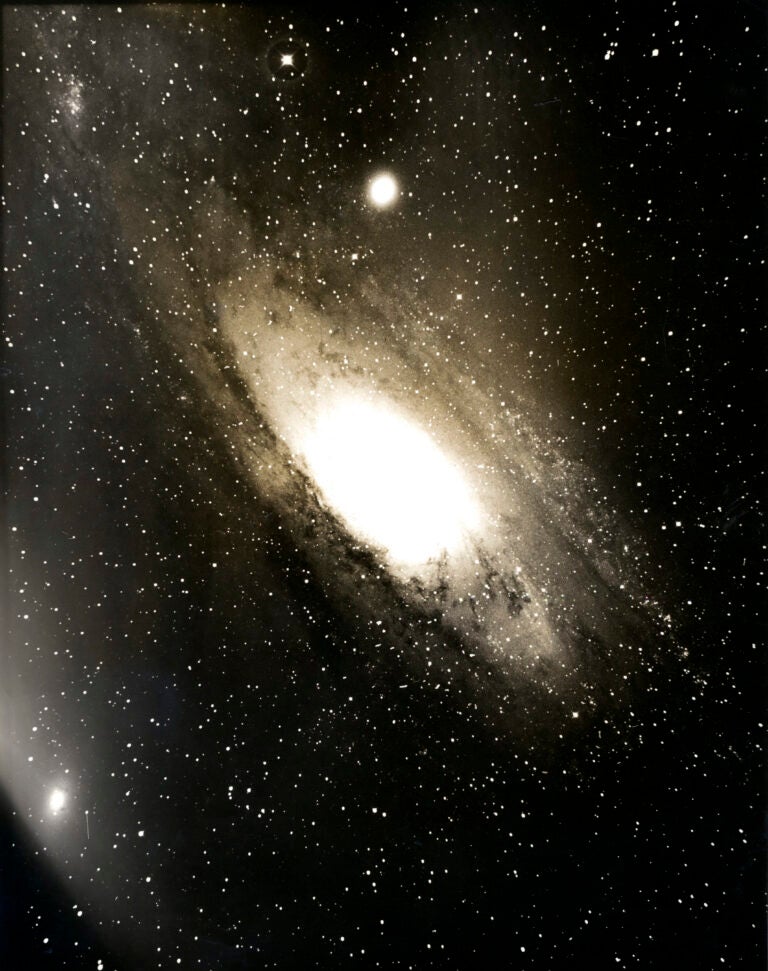

The findings redefine what scientists think of as galaxies. Galaxies may not have a set boundary of stars, but instead stretch out to great distances, forming a vast interconnected sea of stars.

Observations from the Cosmic Infrared Background Experiment (CIBER) are helping settle a debate on the origins of this background infrared light in the universe, previously detected by NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope: whether it comes from these streams of stripped stars too distant to be seen individually, or from the first galaxies to form in the universe.

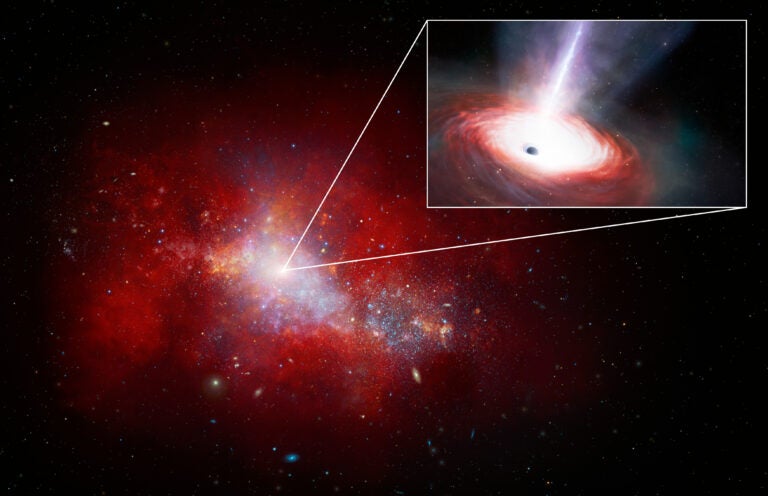

“We think stars are being scattered out into space during galaxy collisions,” said Michael Zemcov from the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). “While we have previously observed cases where stars are flung from galaxies in a tidal stream, our new measurement implies this process is widespread.”

Using suborbital sounding rockets, which are smaller than those that carry satellites to space and are ideal for short experiments, CIBER captured wide-field pictures of the cosmic infrared background at two infrared wavelengths shorter than those seen by Spitzer. Because our atmosphere itself glows brightly at these particular wavelengths of light, the measurements can only be done from space.

“It is wonderfully exciting for such a small NASA rocket to make such a huge discovery,” said Mike Garcia from NASA Headquarters. “Sounding rockets are an important element in our balanced toolbox of missions from small to large.”

During the CIBER flights, the cameras launch into space and then snap pictures for about seven minutes before transmitting the data back to Earth. Scientists masked out bright stars and galaxies from the pictures and carefully ruled out any light coming from more local sources, such as our Milky Way. What’s left is a map showing fluctuations in the remaining infrared background light, with splotches that are much bigger than individual galaxies. The brightness of these fluctuations allows scientists to measure the total amount of background light.

To the surprise of the CIBER team, the maps revealed a dramatic excess of light beyond what comes from the galaxies. The data showed that this infrared background light has a blue spectrum, which means it increases in brightness at shorter wavelengths. This is evidence the light comes from a previously undetected population of stars between galaxies. Light from the first galaxies would give a spectrum of colors that is redder than what was seen.

“The light looks too bright and too blue to be coming from the first generation of galaxies,” said James Bock from Caltech and JPL. “The simplest explanation, which best explains the measurements, is that many stars have been ripped from their galactic birthplace, and that the stripped stars emit on average about as much light as the galaxies themselves.”

Future experiments can test whether stray stars are indeed the source of the infrared cosmic glow. If the stars were tossed out from their parent galaxies, they should still be located in the same vicinity. The CIBER team is working on better measurements using more infrared colors to learn how stripping of stars happened over cosmic history.