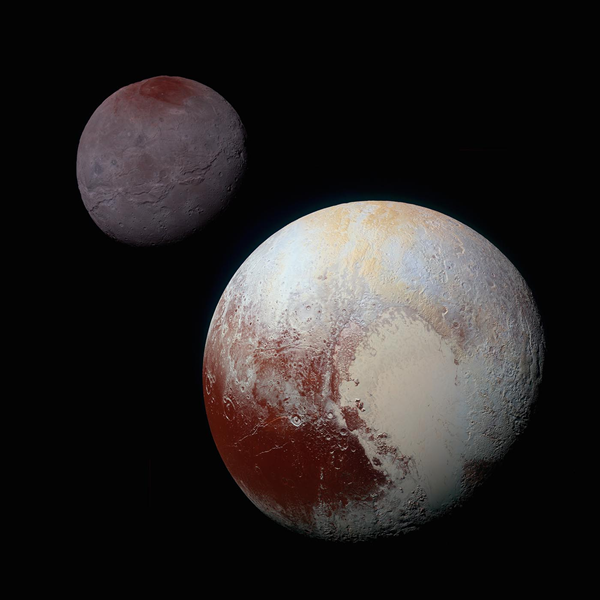

Thanks to all the information pouring in from NASA’s New Horizons mission, Pluto is making a comeback. As New Horizons principle investigator Alan Stern says, “Pluto is the new Mars” – and that’s not just because of its rising popularity.

The nickname, which Stern credits fellow New Horizons team member Jeff Moore with bestowing, comes in part from several intriguing similarities the distant icy world shares with the famous red planet. Both boast an array of surface and atmospheric puzzles sure to keep scientists intrigued for some time.

“There are really so many ways Pluto reminds us of Mars,” says Stern.

Atmospheric Decline

Puzzling atmospheric questions linger over Mars and Pluto. For Mars, the questions involve how its atmosphere disappeared and what that meant for any liquid on the planet’s surface. Pluto is also losing its atmosphere, but at a far slower rate than scientists expected before New Horizons arrived. According to Stern, the atmosphere is escaping about 500 times slower than estimated before the flyby.

That may come from a cooler-than-expected upper atmosphere, which slows down how much material is lost. Something in the air is keeping things chilly, but exactly what remains unknown.

“We are still searching for that mystery molecule that can explain this much cooler upper atmosphere,” Stern said.

A mystery molecule isn’t the only thing floating in the air. Pluto, like Mars, has a handful of tenuous clouds. On both planets, the clouds could suggest unusual weather patterns that, at least on Pluto, were unexpected.

Order the first of its kind Pluto globe exclusively from Astronomy magazine.

Learn More

Like Mars, Pluto may have had a much thicker atmosphere in its past. With an orbit of almost 250 years, temperatures on the dwarf planet can vary significantly over its year, allowing the atmosphere to pile up. A thicker atmosphere could affect how material on the surface behaves. Some of the terrain features suggest that Pluto may have once had liquid pooling on and running across its surface, Stern said.

Heart of Pluto

One of the most striking features on Pluto is its giant heart-shaped basin, informally dubbed by the team as Tombaugh Regio. Like Hellas Basin on Mars, the memorable landmark was most likely caused by a massive object striking the planet. Speaking at the American Astronomical Society’s Division for Planetary Sciences meeting in Pasadena, California, Stern blamed a 40- to 60-kilometer Kuiper Belt object for carving out Pluto’s heart.

Mars has kept the world intrigued with increasing evidence that water flowed across its surface, and suggestions that it may still occasionally trickle today. While Pluto is too cold for water, its features also show evidence of sculpting by easily evaporated materials known as volatiles. For Pluto, the volatile of choice is nitrogen ice.

The northern “lobe” of the heart, Sputnik Planitia, is made up of frozen blocks of nitrogen ice.(Formerly known as Sputnik Planum, the feature is now known to be a sunken plain, or planitia, rather than a raised plain, or planum, Stern said.) After the impact excavated the basin, the volatile material rushed to fill the void.

“Nitrogen ice wants to live in Sputnik Planitia,” says New Horizons scientist William McKinnon.

The ice is heated from beneath and wells upward, then freezes when it draws near the surface. The resulting convection patterns are visible in the enormous blocks. The plain also shows signs of currents and flow patterns, Stern said.

Glaciers dot both worlds. On Mars, they are primarily confined to the cooler poles; on Pluto, they collect at the edge of the planitia, New Horizons revealed.

Pluto’s Glaciers

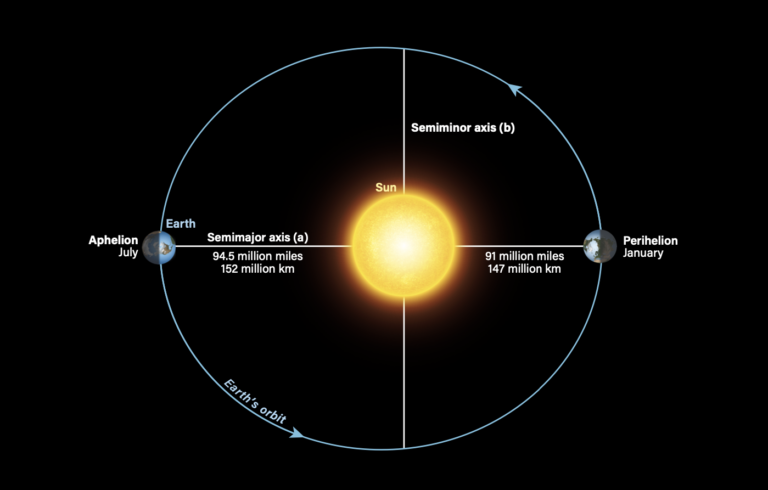

Sputnik Planitia also boasts glaciers not unlike the polar glaciers of Mars. New Horizons revealed that glaciers around the heart of ice flowed recently, and could still be flowing today, despite Pluto’s frigid temperatures. Like Mars, the glaciers are affected by sunlight, but Pluto’s longer trip around the sun means that the glaciers spend more time both in and out of the rays, and its distance minimizes the effects compared to its sibling.

Mountains also tower over both worlds. Mars boasts Olympus Mons, the largest known volcano in the solar system. Built out of flowing rock, the enormous beast has been quiet for at least the last 100 million years, possibly longer. Pluto also appears to boast volcanoes, but instead of spewing hot lava they may produce flowing ice. Found to the south of Pluto’s heart, the massive mountain informally known as Wright Mons stands about 4 kilometers high and 100 kilometers wide, far smaller than its Martian cousin. At their summits, both volcanoes appear to boast calderas, depressions formed when magma flows out of a subsurface chamber. According to Stern, if Wright Mons and its cohorts are volcanoes, there are hints that they were active in the last 470 million years.

The two planets differ in one important way. Over the last few decades, Mars has had a wealth of robotic visitors from Earth, while Pluto has only had one. Stern hopes that the new images will help change that in the upcoming years. While a fleet of flybys would provide more information about the dwarf planet, he thinks an orbiter would be the preferred next step because it would allow scientists to monitor how the icy world changes over short time scales.

“I don’t think we will ever unravel the basics of what’s going on at Pluto until we’ve seen the other side, and until we’ve seen the time domain, how it varies,” he said.

“You need an orbiter to do that. You really can’t do that with just flybys.”

This post originally appeared at Discover Magazine.