Targets for January 2–9, 2014

Naked eye: Large Magellanic Cloud

Small telescope: Open cluster NGC 1664

Large telescope: Reflection nebula NGC 1788

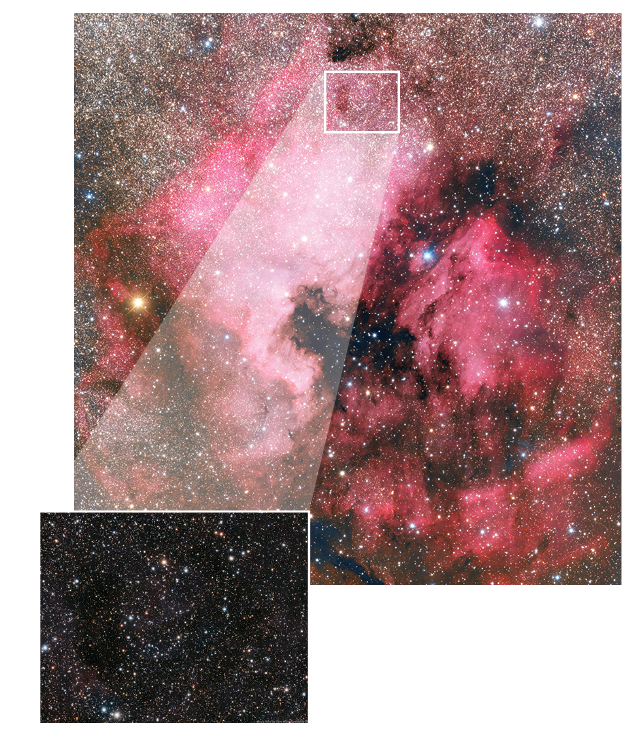

This week’s naked-eye object is the Large Magellanic Cloud in Dorado. Southern Hemisphere observers definitely enjoy the sky’s better half. Below the celestial equator lie the brightest stars, the center of our galaxy, the best dark nebulae, and the most brilliant celestial wonder — the Large Magellanic Cloud. This satellite galaxy of our Milky Way shines with a magnitude of 0.4.

Astronomers classify the Large Magellanic Cloud as an irregular galaxy. It sits in the far southern sky. In fact, its northern edge lies only 25° from the South Celestial Pole.

That means you have to be at a location south of north latitude 25° just to begin to see the Cloud.

Historians often credit Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan (1480–1521) with the discovery of the Large Magellanic Cloud and its neighbor, the Small Magellanic Cloud. That’s incorrect. Both “clouds” had been visible to Southern Hemisphere dwellers throughout history. What Magellan did was make them known to Europe; thus, they bear his name.

No less than 114 NGC objects lie within the Large Magellanic Cloud’s boundaries. The finest, the Tarantula Nebula (NGC 2070), is itself one of the sky’s top wonders.

If we lived on a planet within the Cloud, the Milky Way would dominate the sky. It would shine with a magnitude of –2 and would measure 36° long.

Under a dark sky, start observing the Large Magellanic Cloud without optical aid. Note the galaxy’s brightest region, a luminous bar measuring roughly 5° by 1°. Outside the bar, the brightness drops rapidly, but you’ll still detect an oval haze measuring 6° by 4°. To extend the Cloud’s boundary beyond this — to an astounding 11° by 9° — use binoculars or a rich-field telescope and pan back and forth.

Through a 6-inch or larger telescope and a magnification around 200x, slowly scan back and forth across the Cloud’s face. Pause to examine the many star clusters and nebulae that lie within this galactic neighbor. A nebula filter will help you see the nebulae better but will worsen the view of clusters.

An easy cluster to spot

This week’s small-telescope target is open cluster NGC 1664 in Auriga. You’ll find this attractive object 2° west of magnitude 3.0 Epsilon (ε) Aurigae. It shines at magnitude 7.6 and measures 18′ across. That gives it an area one-third as large as the Full Moon.

Through a 4-inch telescope at 100x, you’ll see three dozen stars. The background star field in this area is rich, but you’ll have no trouble picking out the cluster. The bright star on NGC 1664’s southwestern edge is magnitude 7.5 SAO 39807.

No light of its own

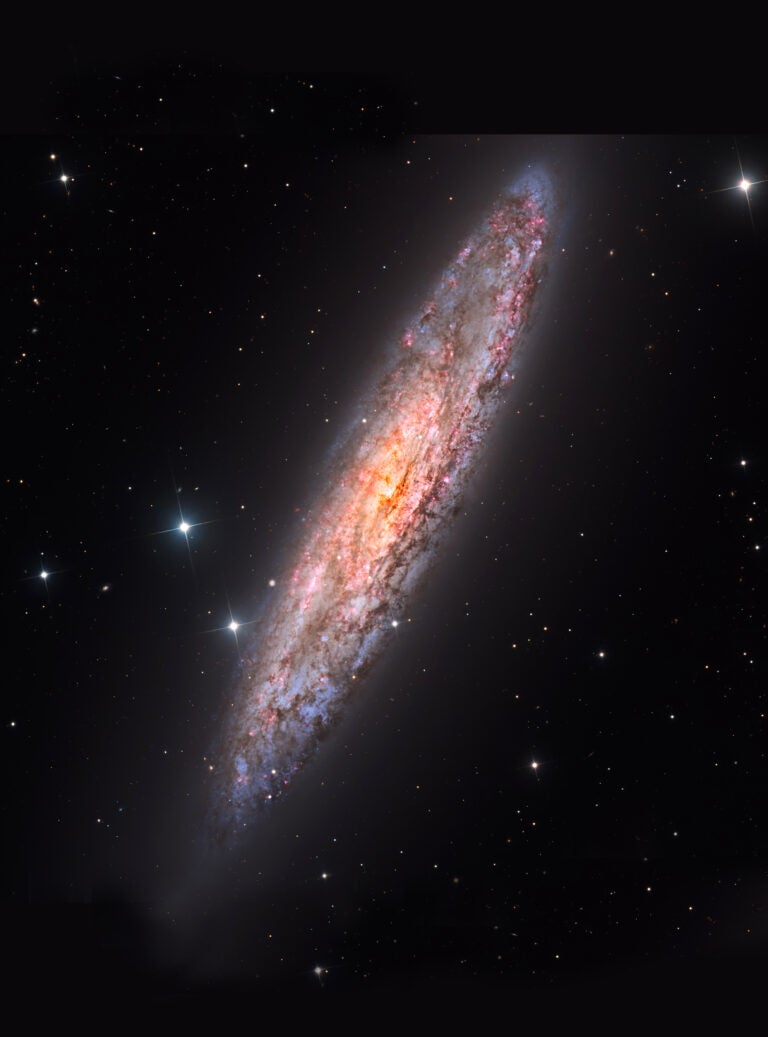

This week’s large-telescope target is reflection nebula NGC 1788 in Orion. This object sits 2° north of magnitude 2.7 Beta (β) Eridani. It measures 5′ by 3′.

Through a 10-inch telescope, you’ll have no trouble spotting NGC 1788. The bright nebula has a diffuse border and features two lobes. The western one surrounds a 10th-magnitude star while the eastern lobe has a small, bright concentration of light at its center.

NGC 1788’s south end meets dark nebula LDN 1616. You’ll have no trouble identifying it because of the lack of background stars over a 5′-wide region.

Expand your observing at Astronomy.com

StarDome

Check out Astronomy.com’s interactive StarDome to see an accurate map of your sky. This tool will help you locate this week’s targets.

The Sky this Week

Get a daily digest of celestial events coming soon to a sky near you.

Observing Talk

After you listen to the podcast and try to find the objects, be sure to share your observing experience with us by leaving a comment at the blog or in the Reader Forums.