Unfortunately, 2014 isn’t the best year for the Perseids. The Moon reaches its Full phase August 10, and it still appears about 90 percent lit by the shower’s peak the morning of the 13th. With bright moonlight in the sky from dusk until dawn, fainter meteors will be washed out and only the bright ones will shine through. Under clear skies, attentive observers could see perhaps 20 to 25 meteors per hour — not great, but better than all but a handful of nights during 2014.

One way to compensate for the Moon’s presence is to wait until an hour or so before morning twilight begins. Position yourself facing north, with the Moon to your back and, if you can manage, behind a building or trees. This will make the sky appear darker. Also try to observe from a rural location, where the lights of the city won’t add to the Moon’s glow

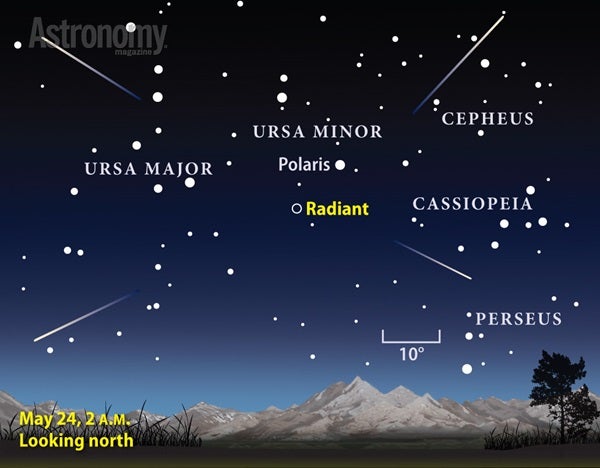

The Perseids begin as tiny specks of dust that hit Earth’s atmosphere at 37 miles per second (59 km/s), vaporizing from friction with the air and leaving behind the streaks of light we call meteors. The meteors appear to radiate from a spot on the border between the constellations Cassiopeia and Perseus (the latter gives its name to the shower). This so-called radiant lies about one-third of the way from the northeastern horizon to the zenith (the overhead point) around midnight local daylight time and climbs higher as dawn approaches.

- The dust particles that create Perseid meteors were born in the comet known as 109P/Swift-Tuttle. This object orbits the Sun once every 130 years; it last returned to the inner solar system in 1992.

- Although 37 miles per second (59 km/s) may seem fast, Perseid meteors are not the quickest among annual showers. The Leonids of November top the charts, hitting our atmosphere at 44 miles per second (71 km/s).

- Although most shower meteors meet their demise high in Earth’s atmosphere, at altitudes between 50 and 70 miles (85 and 115 kilometers), a few bigger particles survive to within 12 miles (20km) of the surface. These typically produce “fireballs” that glow as bright as or brighter than Venus.

- Video: How to observe meteor showers, with Michael E. Bakich, senior editor

- StarDome: Locate the shower’s radiant in Perseus in your night sky with our interactive star chart.

- The Sky this Week: Get your meteor shower info from a daily digest of celestial events coming soon to a sky near you.

- Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter.