Friday, March 17

The variable star Algol in Perseus reaches minimum brightness at 9:14 p.m. EDT, when it shines at magnitude 3.4. If you start viewing as soon as darkness falls, you can watch it more than triple in brightness (to magnitude 2.1) over the course of about five hours. This eclipsing binary star runs through a cycle from minimum to maximum and back every 2.87 days. Algol lies more than halfway to the zenith in the western sky after sunset and sinks low in the northwest after midnight.

Saturday, March 18

Venus appears low in evening twilight during the next few days. This evening, it stands about 5° high in the west a half-hour after sunset. If you have an observing site with an unobstructed view toward the horizon, you should have little trouble spotting the planet because it shines so brightly, at magnitude –4.2. When viewed through a telescope, Venus appears 58″ across and mere 3 percent illuminated. You should be able to detect the planet’s thin crescent through steadily held binoculars.

The Moon reaches apogee, the farthest point in its orbit around Earth, at 1:25 p.m. EDT. It then lies 251,438 miles (404,650 kilometers) from Earth’s center.

Sunday, March 19

March evenings offer an excellent chance to see the zodiacal light. From the Northern Hemisphere, late winter and early spring are great times to observe this elusive glow after sunset. It appears slightly fainter than the Milky Way, so you’ll need a clear moonless sky and an observing site located far from the city. With the Moon now gone from the evening sky, prime viewing conditions will extend through March 28. Look for the cone-shaped glow, which has a broad base and points nearly straight up from the western horizon, after the last vestiges of twilight have faded away.

Monday, March 20

Last Quarter Moon occurs at 11:58 a.m. EDT. You can find the half-lit orb rising in the east along with the background stars of Sagittarius around 2 a.m. local daylight time; it hangs relatively low in the south-southeast as twilight begins. Look about 3° to our satellite’s lower right and you should pick up the bright glow of Saturn. The ringed planet shines at magnitude 0.5, significantly brighter than any of Sagittarius’ stars. When viewed through a telescope, Saturn displays a 17″-diameter disk surrounded by a spectacular ring system that spans 38″ and tilts 26° to our line of sight.

For those of you tired of winter weather, good news: Spring officially begins today. Earth’s vernal equinox occurs at 6:29 a.m. EDT, which marks the moment when the Sun crosses the celestial equator traveling north. The Sun rises due east and sets due west today. If the Sun were a point of light and Earth had no atmosphere, everyone would get 12 hours of sunlight and 12 hours of darkness. But our blanket of air and the finite size of our star make today a few minutes longer than 12 hours.

Tuesday, March 21

Mars continues to put on a nice show these March evenings. It appears nearly 20° high in the west once twilight fades to darkness and doesn’t set until after 10 p.m. local daylight time. The magnitude 1.4 Red Planet lies among the background stars of Aries the Ram. Unfortunately, Mars shows no detail on its 4″-diameter disk when viewed through a telescope.

Wednesday, March 22

One of the spring sky’s finest deep-sky objects, the Beehive star cluster (M44) in the constellation Cancer the Crab, lies high in the south around 9 p.m. local daylight time. With the naked eye under a dark sky, you should be able to spot this star group as a misty cloud of light. But the Beehive explodes into dozens of stars through binoculars or a small telescope.

Thursday, March 23

Mercury has started its finest evening appearance of the year for observers at mid-northern latitudes. The innermost planet lies nearly 10° above the western horizon a half-hour after sunset. Shining at magnitude –1.0, it stands out against the twilight glow through binoculars and should show up to the naked eye once you know where to look. A telescope reveals Mercury’s 6″-diameter disk, which appears three-quarters lit. The planet will reach the peak of this apparition at greatest elongation April 1.

Friday, March 24

One of the sky’s largest asterisms — a recognizable pattern of stars separate from a constellation’s form — occupies center stage on March evenings. To trace the so-called Winter Hexagon, start with southern Orion’s luminary, Rigel. From there, the hexagon makes a clockwise loop. The second stop is brilliant Sirius in Canis Major. Next, pick up Procyon in the faint constellation Canis Minor, then the twins Castor and Pollux in Gemini, followed by Capella in Auriga, Aldebaran in Taurus, and finally back to Rigel.

Saturday, March 25

The Big Dipper’s familiar shape rides high in the northeast on March evenings. The spring sky’s finest binocular double star marks the bend of the Dipper’s handle. Mizar shines at 2nd magnitude, some six times brighter than its 4th-magnitude companion, Alcor. Even though these two are not physically related, they make a fine sight through binoculars. (People with good eyesight often can split the pair without optical aid.) A small telescope reveals Mizar itself as double — and these components do orbit each other.

Venus reaches inferior conjunction at 6 a.m. EDT. This position places the inner planet most nearly between Earth and the Sun (precisely 8° north-northwest of our star), so it is lost in the glare. But the brilliant world orbits the Sun quickly, and it will return to view before dawn next week.

Sunday, March 26

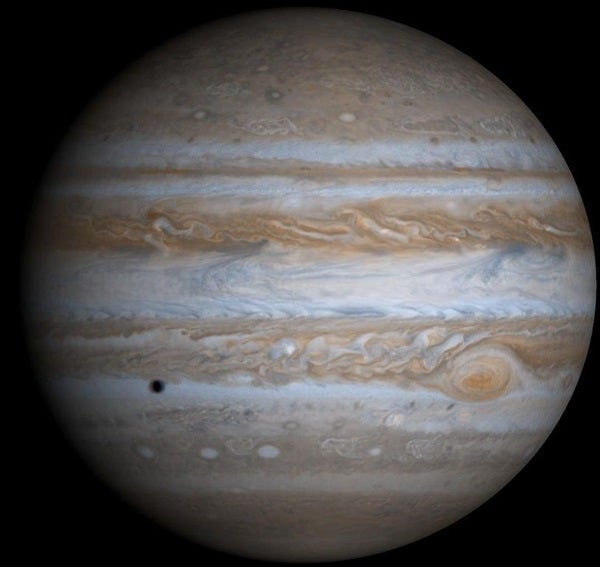

Jupiter rises before 9 p.m. local daylight time and climbs highest in the south around 2 a.m. The giant world shines at magnitude –2.4 against the backdrop of central Virgo, some 6° north-northwest of that constellation’s brightest star, 1st-magnitude Spica. Even a small telescope reveals Jupiter’s 44″-diameter disk and four bright moons.