The Ursid meteor shower peaks before dawn today. The shower’s radiant — the point from which the meteors appear to originate — lies in the constellation Ursa Minor, near the top of the Little Dipper’s bowl. The radiant is visible in the north all night, but climbs higher as dawn approaches. With the Moon out of the sky, viewers under a clear, dark sky should be able to see an average of 10 Ursid meteors per hour.

Saturday, December 23

The variable star Algol in Perseus reaches minimum brightness at 8:00 p.m. EST, when it shines at magnitude 3.4. If you start watching it after darkness falls, you can see it more than triple in brightness, to magnitude 2.1, over the course of about five hours. This eclipsing binary star runs through a cycle from minimum to maximum and back every 2.87 days. Algol appears in the eastern sky after nightfall and passes nearly overhead around 9 p.m. local time.

Sunday, December 24

If you’re looking for a Christmas star to mark the holiday, you can’t go wrong with brilliant Sirius. The brightest star in the sky (after the Sun, of course) gleams at magnitude –1.5. This makes it nearly four times brighter than the next brightest star visible from mid-northern latitudes: Arcturus in the constellation Boötes. Sirius currently rises before 8 p.m. local time and ascends in the southeast throughout the evening hours.

Monday, December 25

You can find the First Quarter Moon high in the south as darkness falls, then watch as it sinks toward the western horizon throughout the evening hours. Our satellite officially reaches First Quarter phase at 4:20 a.m. EST tomorrow morning. The Moon spends this evening among the background stars of southern Pisces, due south of the Great Square of Pegasus.

Tuesday, December 26

For those who recently caught the observing bug, the so-called Summer Triangle must seem like a huge misnomer. That’s because this asterism remains on view after darkness falls in late December. Look for Vega, the fifth-brightest star in the sky and the brightest triangle member, in the northwest after nightfall. Deneb lies above Vega and about halfway to the zenith. Deneb marks the top of another asterism, the Northern Cross, which stands nearly straight up from the horizon on December evenings. Altair, the third triangle member, appears due west and near the same altitude as Vega. The trio remains on view until Altair sets around 8 p.m. local time.

If you’re game for a quick evening challenge, try to spot Neptune through binoculars. The distant planet lies nearly halfway to the zenith in the southwest at the end of evening twilight and doesn’t set until 10 p.m. local time. The magnitude 7.9 world appears against the backdrop of Aquarius, 0.5° south-southeast of the 4th-magnitude star Lambda (λ) Aquarii. You’ll need binoculars to spy Neptune and a telescope to see its blue-gray disk, which spans 2.3″.

Thursday, December 28

A lone bright star now hangs low in the south-southwest during early evening. First-magnitude Fomalhaut — often called “the Solitary One” — belongs to the constellation Piscis Austrinus the Southern Fish. From mid-northern latitudes, it appears below the Great Square of Pegasus and about 20° above the horizon. How solitary is Fomalhaut? The nearest 1st-magnitude star to it, Achernar at the southern end of Eridanus the River, lies some 40° away.

Friday, December 29

Although Uranus reached opposition more than two months ago, it remains a tempting target. The outer planet climbs highest in the south around 7 p.m. local time, when it appears two-thirds of the way to the zenith. The magnitude 5.8 world lies in southeastern Pisces, 3.6° west of the 4th-magnitude star Omicron (ο) Piscium. Although Uranus shines brightly enough to glimpse with the naked eye under a dark sky, binoculars make the task much easier. A telescope reveals the planet’s blue-green disk, which spans 3.6″.

Saturday, December 30

The waxing gibbous Moon takes center stage this afternoon and evening when it passes in front of (occults) the bright star Aldebaran for observers across most of the United States and Canada. Luna’s dark limb covers the star between 6 and 7 p.m. EST — the exact time depends on your location. Observers in the eastern half of North America can see the disappearance after sunset; the event occurs in daylight farther west. First-magnitude Aldebaran returns to view from behind the Moon’s bright limb roughly an hour later. Binoculars or a telescope will deliver the best views of this dramatic event.

Mars rises just before 3 a.m. local time this morning while Jupiter follows a mere 15 minutes later. The magnitude 1.5 Red Planet lies just 3° west of the giant world, which gleams at magnitude –1.8. If you wait a couple of hours for them to climb higher in the southeast, you’ll notice they bracket the 3rd-magnitude star Zubenelgenubi (Alpha [α] Librae). The planets’ proximity heralds their stunning conjunction a week from today.

Monday, January 1

Full Moon occurs at 9:24 p.m. EST, but our satellite looks completely illuminated all night. You can find it rising in the east around sunset and peaking high in the south just after midnight. The Moon lies in central Gemini, roughly 15° southwest of that constellation’s brightest star, 1st-magnitude Pollux. The Moon also reaches perigee today, at 4:49 p.m. EST, when it lies 221,559 miles (356,565 kilometers) from Earth. That makes this Full Moon the closest and biggest (33.5′ across) of 2018, and many people will feel compelled to call it a “Super Moon.”

Mercury reaches the peak of its current apparition this morning. The innermost planet lies 23° west of the Sun and appears 11° above the southeastern horizon 30 minutes before sunrise. Shining at magnitude –0.3, it shows up nicely through the twilight glow. (If you don’t spot it right away, binoculars will bring it into view.) A telescope reveals Mercury’s 7″-diameter disk, which appears slightly more than half-lit.

Wednesday, January 3

Earth reaches perihelion, the closest point to the Sun during its year-long orbit, at 1 a.m. EST. The two then lie 91.4 million miles (147.1 million kilometers) apart. It surprises many people to learn that Earth comes closest to the Sun in the dead of winter, but the cold weather in the Northern Hemisphere at this time of year arises because the Sun traces a low arc across the sky.

Thursday, January 4

The Quadrantid meteor shower reaches its peak this morning. Unfortunately, the nearly Full Moon will drown out fainter meteors and leave only the bright ones to shine through. The Quadrantids do generate a high percentage of bright meteors, however, so the shower should deliver a smattering of “shooting stars” to observers who brave the cold. The meteors appear to radiate from a spot in the northern part of the constellation Boötes, which climbs high in the northeast as dawn approaches.

Although people in the Northern Hemisphere experienced the shortest day of the year more than two weeks ago (at the winter solstice December 21), the Sun has continued to rise slightly later with each passing day. That trend stops this morning for those at 40° north latitude. Tomorrow’s sunrise will arrive about a second earlier than today’s. This turnover point depends on latitude. If you live farther north, the switch occurred a few days ago; closer to the equator, the change won’t happen until later in January.

Friday, January 5

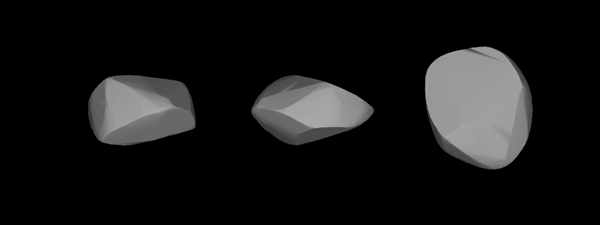

Grab your binoculars or telescope and hunt down asteroid 20 Massalia during January’s first week. This 9th-magnitude object lies among the background stars of eastern Taurus and climbs highest in the south during the late evening hours. Start at 3rd-magnitude Zeta (ζ) Tauri, the star that marks the tip of the Bull’s southern horn. Then, take a quick look at the Crab Nebula (M1) 1° to the northwest before sliding 1.6° farther west to find 5th-magnitude 114 Tau. Massalia currently lies 1° due west of this star.

Two of the finest deep-sky objects shine prominently on evenings in early January. The Pleiades and Hyades star clusters climb highest in the south during midevening but remain conspicuous nearly the whole night. The Pleiades, also known at the Seven Sisters and M45, appears like a small dipper to naked eyes. The larger Hyades forms the V-shaped head of Taurus the Bull. Although both look nice with the naked eye, binoculars show them best.

Sunday, January 7

Mars and Jupiter enjoy a stunning conjunction this morning. The two planets stand just 16′ apart (half the Full Moon’s diameter). This is the closest they’ve been since September 2004, though they were then just a few degrees from the Sun and lost in our star’s glare. They haven’t been this close and visible since January 1998. The pairing looks great with the naked eye or binoculars. A telescope shows both in a single low-power field of view. Mars appears 5″ across while Jupiter, despite lying three times farther away, spans 34″.