Although Jupiter reached opposition and peak visibility in early May, it remains a conspicuous object from evening twilight until it sets around 10:30 p.m. local daylight time. Jupiter shines at magnitude –1.9 and dominates the southwestern sky after Venus sets around 9 p.m. The gas giant resides among the background stars of Libra the Scales; this evening, it lies 1.9° due east of Zubenelgenubi (Alpha [α] Librae). If you view the planet through a telescope, its disk spans 35″ and displays spectacular cloud-top detail.

Saturday, September 1

Mars reached its peak about a month ago, and it remains a glorious sight. The Red Planet appears in the south-southeast as darkness falls and climbs highest in the south around 10 p.m. local daylight time. The world shines at magnitude –2.1, making it the second-brightest point of light in the night sky after Venus. When seen through a telescope, surface features on the 21″-diameter disk continue to sharpen as the global dust storm dissipates. Mars’ slow eastward motion relative to the background stars carries it across the border from Sagittarius into Capricornus today.

Sunday, September 2

Last Quarter Moon occurs at 10:37 p.m. EDT. It rises around midnight local daylight time and climbs high in the southeast by the time twilight starts to paint the sky. Earth’s only natural satellite lies just east of the Hyades star cluster and 1st-magnitude Aldebaran in the constellation Taurus the Bull.

Monday, September 3

Observers using binoculars or a telescope should set their sights on Comet 21P/Giacobini-Zinner, which is making its second-best appearance since its discovery in 1900. The comet currently glows at 7th magnitude against the backdrop of Auriga the Charioteer, a region that rises in the evening and climbs high before dawn. Giacobini-Zinner lies within 2° of magnitude 0.1 Capella this morning. (It was similarly close yesterday morning.)

The variable star Algol in Perseus reaches minimum brightness at 1:40 a.m. EDT tomorrow morning. Observers on the East Coast who start watching around midevening can see the star’s brightness diminish by 70 percent over the course of about five hours. Those in western North America will see Algol brighten noticeably from late evening until dawn starts to paint the sky, when the star passes nearly overhead. This eclipsing binary system runs through a cycle from minimum (magnitude 3.4) to maximum (magnitude 2.1) and back every 2.87 days.

Wednesday, September 5

Mercury makes an impressive appearance before dawn in early September. The innermost planet stands 7° above the eastern horizon 30 minutes before sunrise. Despite bright twilight, Mercury stands out because it shines brightly, at magnitude –1.1. If you view the scene through binoculars, you should see the 1st-magnitude star Regulus 1.5° below it. (The two will appear side by side tomorrow morning.) A telescope reveals Mercury’s 6″-diameter gibbous disk.

Thursday, September 6

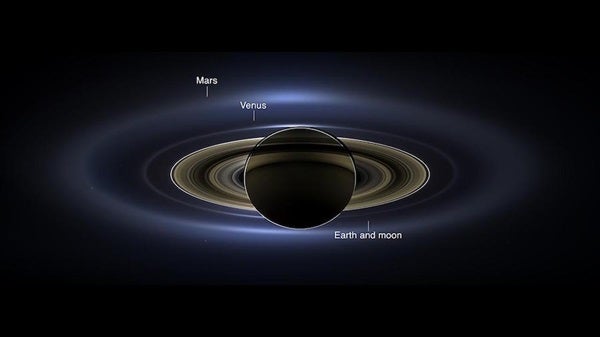

Saturn appears nearly due south and at its highest altitude as darkness falls in early September. The ringed planet shines at magnitude 0.4, more than a full magnitude brighter than any of the background stars in its host constellation, Sagittarius. Saturn’s slow westward motion against this rich Milky Way backdrop comes to a halt today. Center the planet in your binoculars and you’ll see the Lagoon Nebula (M8) 2.2° to the southwest and the Trifid Nebula (M20) 1.7° to the west-southwest. But the best views come through a telescope. Even the smallest instrument shows Saturn’s 17″-diameter disk surrounded by a dramatic ring system that spans 39″ and tilts 27° to our line of sight.

Neptune reaches opposition and peak visibility tonight. Because it lies opposite the Sun in our sky, it rises at sunset and appears highest in the south around 1 a.m. local daylight time. But you can start searching for it by 10 p.m., when it stands nearly one-third of the way from the southeastern horizon to the zenith. Neptune glows at magnitude 7.8, bright enough to spot through binoculars if you know where to look. The trick is to find the 4th-magnitude star Phi (φ) Aquarii, which lies about 15° (two binocular fields) east-southeast of Aquarius’ distinctive Water Jar asterism. At opposition, Neptune appears 2.3° west-southwest of Phi. When viewed through a telescope, Neptune shows a blue-gray disk measuring 2.4″ across.

The Moon reaches perigee, the closest point in its orbit around Earth, at 9:20 p.m. EDT. It then lies 224,533 miles (361,351 kilometers) away from us.

Saturday, September 8

Venus dominates the twilight sky after sunset. The dazzling object shines at magnitude –4.7 among the background stars of south-central Virgo. The planet appears 9° high 30 minutes after sundown and sets shortly after 8:30 p.m. local daylight time. A telescope reveals Venus’ disk, which spans 32″ and appears about one-third lit.

Astroimagers will want to target Comet 21P/Giacobini-Zinner these weekend mornings. The 7th-magnitude comet slides through a photogenic region of the winter Milky Way that includes the bright star clusters M36 and M38.

Sunday, September 9

New Moon occurs at 2:01 p.m. EDT. At its new phase, the Moon crosses the sky with the Sun and so remains hidden in our star’s glare.

Although you can’t see the New Moon, its absence from the morning sky these next two weeks provides observers with an excellent opportunity to view the zodiacal light. From the Northern Hemisphere, this time of year is the best for viewing the elusive glow before sunrise. It appears slightly fainter than the Milky Way, so you’ll need a clear moonless sky and an observing site located far from the city. Look for a cone-shaped glow that points nearly straight up from the eastern horizon shortly before morning twilight begins (around 5 a.m. local daylight time at mid-northern latitudes). The Moon remains out of the morning sky until September 23, when the waxing gibbous returns and overwhelms the much fainter zodiacal light.