The passing of Tom Stafford leaves only seven surviving Apollo Moon voyagers. Nicknamed “Mumbles”, this Air Force three-star general dodged death on the launchpad, set records as one of the fastest humans in history, and won the Congressional Space Medal of Honor for an epic mission of space détente with Soviet Russia.

Born on Sept. 17, 1930, Thomas Patten Stafford was the progeny of a dentist father and a teacher mother. A voracious reader, he watched silvery DC-3 airliners soar over the family home in Weatherford, Oklahoma, a city that today boasts an airport, museum, and university buildings named in his honor.

It was Japan’s notorious Pearl Harbor attack that galvanized Stafford into action. Aged 11, he earned cash delivering newspapers to buy and build model airplanes. At 14, he made his first flight in a tiny Piper Cub – “eager,” he wrote in his memoir, We Have Capture, “to become a fighter pilot and help win the war.”

Stafford missed action in World War II, instead captaining his high school football team. A mischievous youth, he shot out streetlamps with a BB gun, tossed a firecracker into a police station, and goaded classmates to disrupt their English lessons with synchronised coughing. “The neighbors could always tell when I’d been caught,” he wrote. “I would be out front painting the fence, like Tom Sawyer.”

As an Oklahoma National Guard member, Stafford expertly calculated maneuvers to hit howitzer targets and aided the town of Leedey after its 1947 tornado. He joined the Naval Academy and while serving on the battleship USS Missouri met a midshipman named John Young. Neither could have imagined they would someday fly to the Moon together.

After his graduation from the academy in 1952 and marriage to Faye Shoemaker in 1953, Stafford’s desire to fly the F-86 jet — “the hottest thing in the sky” — drew him to the Air Force. But with limited early prospects, he considered an airline career instead.

Then he read excitedly about the up-and-coming F-100 and F-104 supersonic fighters. He tore up his airline application and in 1958 (by now the father of two girls, Karin and Dionne) was promoted and picked to attend the coveted Flight Test School at Edwards Air Force Base in California.

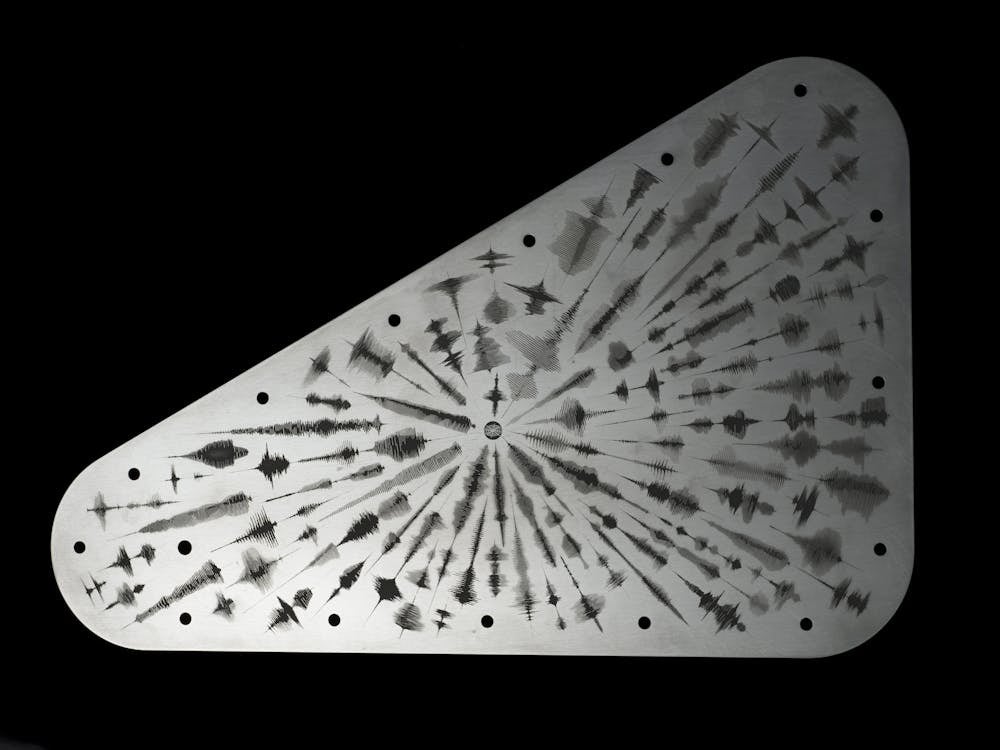

The workload was intense. “Each morning’s flight data generated a pile of data from handwritten notes, recording cameras, oscilloscopes and other instruments,” Stafford wrote. “We had to reduce this data to a terse report that we submitted to the instructors and we had a test every Friday.” Out of this test pilot crucible, America’s first astronauts were drawn.

After Stafford graduated top of his class in 1959, he stayed at Edwards as an instructor and co-authored two flight test manuals. In September 1962, NASA chose him as an astronaut.

The 6-foot-tall Stafford credited NASA’s decision to relax height rules as a key enabler in getting selected. McDonnell Aircraft, builder of the Gemini spacecraft, had to remove sections of overhead insulation so taller astronauts could fit its snug cabin. The slight bump caused by this modification became known as “the Stafford Bump.”

Stafford was assigned to Gemini 3, the first manned flight of the series, but his hopes of being first in his class to reach space evaporated when crewmate Alan Shepard was grounded by an inner-ear ailment. By now recognised as an expert on space rendezvous (an essential prerequisite for landing on the Moon), Stafford was next partnered with Wally Schirra on Gemini 6 to rendezvous and dock with an unmanned Agena-D target spacecraft.

But the Agena exploded minutes after liftoff on Oct. 25, 1965, grounding the renamed Gemini 6A until December. A new plan evolved to rendezvous (but not dock) with the manned Gemini 7, launched on Dec. 4. Eight days later, Schirra and Stafford felt the engines of their Titan II rocket roar to life. Then, 1.2 seconds later, they fell silent.

The men faced a life-or-death gamble. If the Titan had risen a mere inch, it could fall back onto the pad and explode. But ejecting from Gemini 6A’s oxygen-rich cabin offered no better odds of survival. “Given that we’d been soaking in pure oxygen for two hours, any spark, especially the ignition of an ejection seat rocket, would have set us on fire,” wrote Stafford. “We’d have been two Roman candles shooting off into the sand and palmetto trees.”

Sensing no motion in the Titan, Schirra sat tight, a gutsy decision that saved their lives and kept Gemini 6A intact to fly on Dec. 15. Six hours into their day-long flight, with Stafford using a circular slide rule and plotting chart to cross-check radar data as Schirra flew the ship, they maneuvered within a foot (30 centimeters) of Gemini 7… so close that the crews held up “Beat Army” and “Beat Navy” cards to tease the other.

Stafford’s second flight, 169 days later, set a record for the shortest interval between missions by one astronaut; a record that remained unbroken until 1984. But it emerged from an appalling tragedy: When Gemini 9 astronauts Elliot See and Charlie Bassett died in an aircraft crash in February 1966, backup crewmen Stafford and Gene Cernan were tapped to fly in their stead.

In another twist of fate, the renamed Gemini 9A’s Agena target was lost during its May 17 launch. A replacement, the Augmented Target Docking Adapter (ATDA) was hastily launched on June 1, but its docking collar failed to separate and hung open like, Stafford said, an angry alligator. Stafford and Cernan could rendezvous with it, but not dock.

With two lost Agenas and two scrubbed launches, Stafford seemed jinxed. And the launchpad crew teased him mercilessly, even taping a note to the gantry’s elevator door. “Tom and Gene,” it read. “Notice the down capability for this elevator has been removed. Let’s have a good flight.”

Launched on June 3, 1966, Gemini 9A’s three days in space achieved multiple rendezvous with the ATDA but a two-hour spacewalk by Cernan was troubled. His suit’s environmental control system couldn’t keep up with the humidity and carbon dioxide produced by his exertions, exhausting him and blinding him in his own sweat. A lack of handholds and positioning aids made the simplest tasks impossible. Stafford and Cernan returned to Earth with a sober appreciation of the hazards of spaceflight.

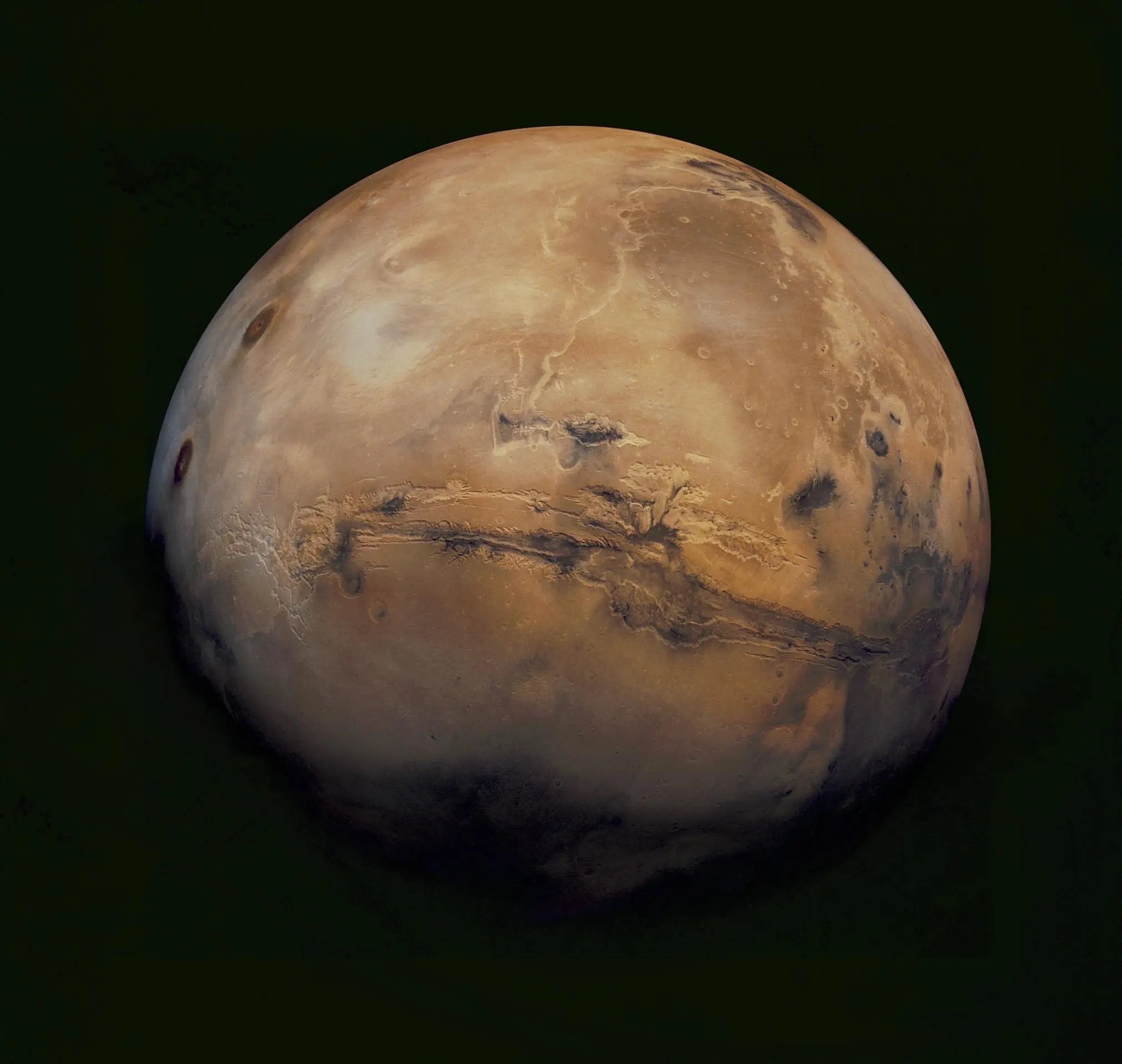

Three years later, on May 18, 1969, Stafford commanded Apollo 10, a dress rehearsal in lunar orbit for the first manned landing on the Moon. Launched atop a mighty Saturn V, he was joined by Young — his former Missouri shipmate — and Cernan.

Stafford and Cernan flew the lunar module, named “Snoopy,” to just 9 miles (15 kilometers) above the Moon’s rocky surface. Aboard the command module “Charlie Brown,” Young became the first person to fly solo in lunar orbit. Returning home on May 26, they re-entered Earth’s atmosphere at a blistering 24,816 mph (39,937 km/h), the highest speed ever attained by humans and a record still unbroken today.

For the next two years, Stafford was chief of NASA’s astronaut corps, notably visiting Moscow to represent President Richard Nixon at the funerals of three cosmonauts killed during a reentry disaster. Promoted to brigadier general at 42, he was the youngest flag officer in U.S. military history.

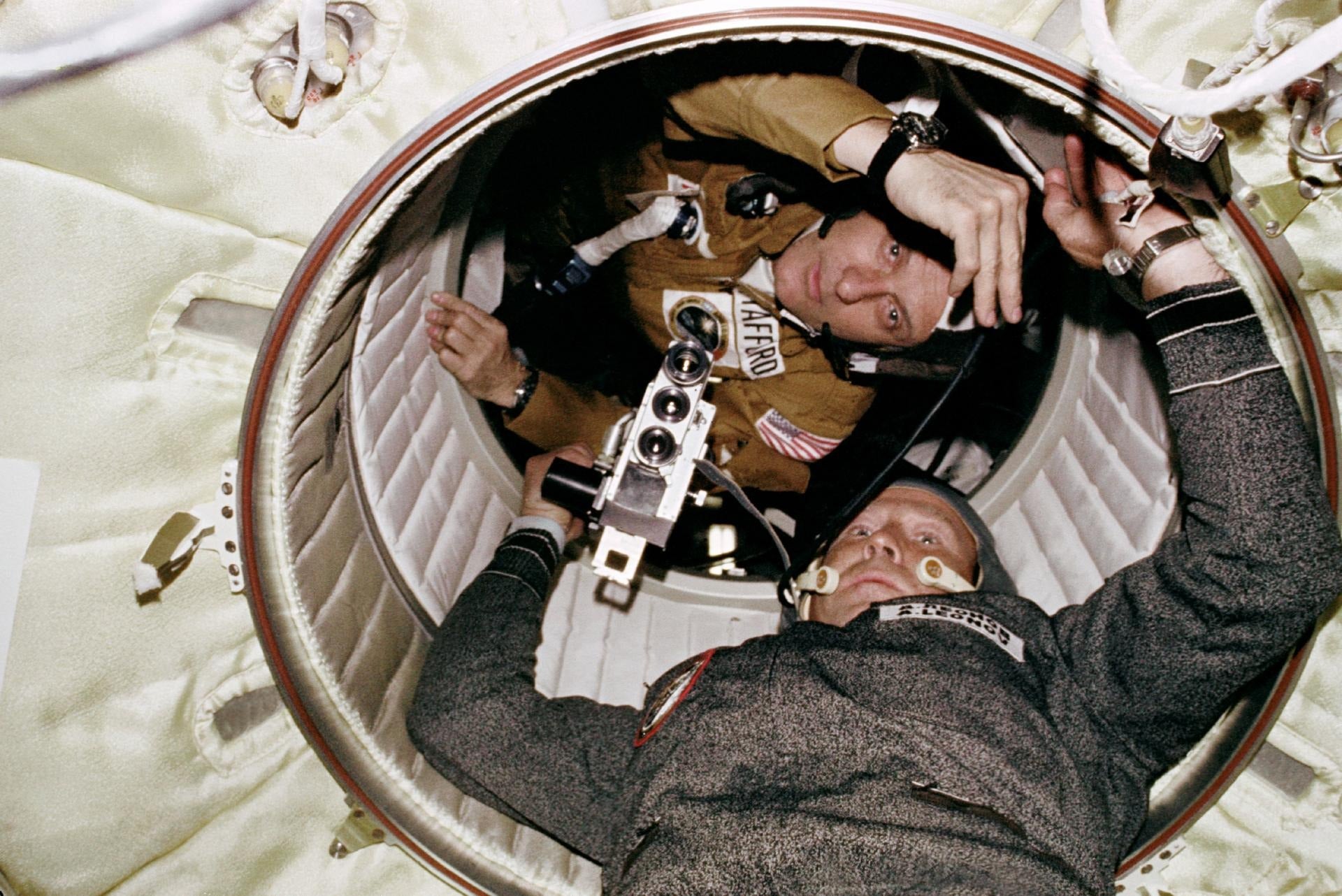

And on Stafford’s fourth flight, the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in July 1975, he became the first general officer to fly in space. His Apollo 18 crew of Vance Brand and Deke Slayton docked with Russia’s Soyuz 19, manned by cosmonauts Alexei Leonov and Valeri Kubasov. It was the first joint mission between old Cold War foes.

After docking, Stafford opened the hatch and shook Leonov’s hand.

“Glad to see you,” said Leonov in English.

“Very good, comrade,” replied Stafford in Russian.

Despite the language barrier, a lifelong friendship blossomed between them and endured until Leonov’s death in 2019. Leonov would later joke that Stafford’s tendency to mumble Cyrillic consonants in his strong Midwestern accent yielded a peculiar dialect: not English or Russian, but rather Oklahomsky.

But the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project almost ended in disaster when lethal nitrogen tetroxide leaked into Apollo 18’s cabin via a vent valve just before splashdown. “I knew I had toxic hypoxia,” Stafford recalled, “and I started to grunt-breathe to make sure I got pressure in my lungs to keep my head clear.” He quickly fitted oxygen masks to Brand and Slayton. Thanks to his actions, all three men survived.

After NASA, Stafford commanded the Air Force Flight Test Center at Edwards and during his tenure drove the development of the F-117 stealth fighter and B-2 bomber, famously sketching their specifications onto a piece of hotel stationery. In retirement, he chaired committees charting America’s future in space. And perhaps Stafford’s singular legacy remains his fierce, unwavering support for the space program and the wise vision “Mumbles” provided for space explorers of tomorrow.