Luckily for astronomers, each element and molecule, when heated or excited or transitioning, emits specific, discrete wavelengths of light. This radiation is the atom’s or compound’s fingerprint, uniquely identifying it, whether it lives on Earth or in space.

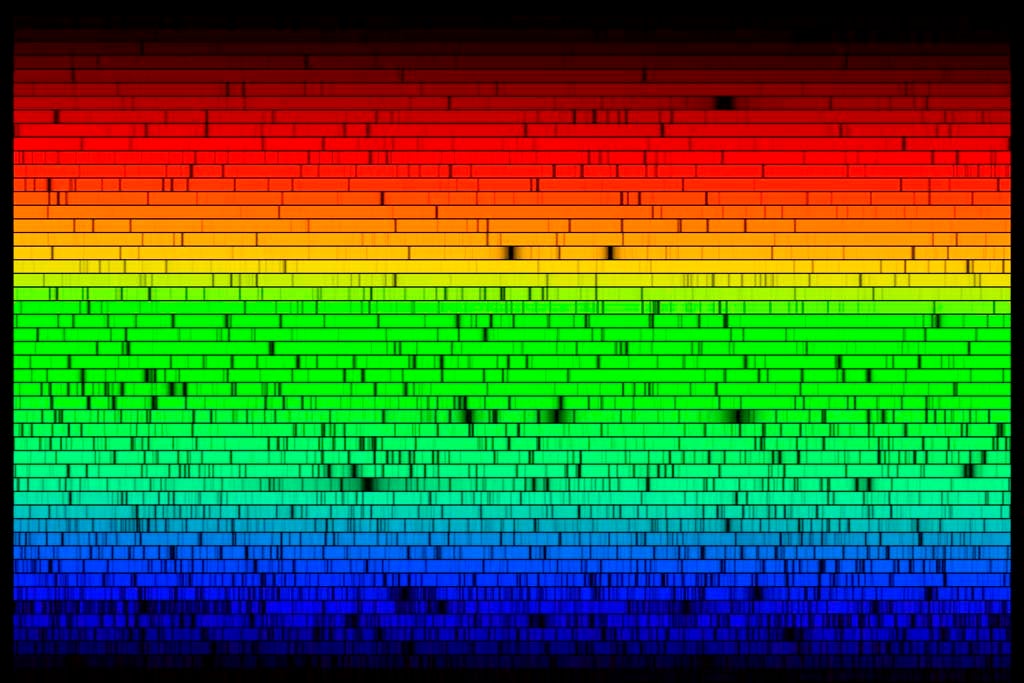

In 1814, German optician Joseph von Fraunhofer discovered that when he passed the Sun’s light through a prism, separating it into component colors, dark lines appeared across the spectrum. Not content merely to notice, he measured the specific wavelengths at which the lines appeared — all 570 of them that he was able to separate. Forty-five years later, German physicist Gustav Kirchhoff and German chemist Robert Bunsen realized that the dark lines matched up with the bright emission lines from simple chemical elements like hydrogen and oxygen. They deduced that the solar atmosphere was absorbing the emissions from these elements, leaving blank spots in the spectrum. Astronomical spectroscopy was born.

Today, astronomers analyze the spectra of distant stars, performing essentially a highly sensitive and more nuanced version of Fraunhofer’s original observations. The intervening 200 years have given them a bit more knowledge about how stars work internally, though. From the relative brightness of various elements’ emissions, scientists can tell how long a star has been burning its fuel, how much mass it’s losing, and what class it belongs to.

The tricky thing about spectral lines is that they change based on how an atom is moving relative to you. Just as a siren becomes higher in pitch as a fire truck approaches you and lower as it speeds away, spectral lines are stretched to longer wavelengths if an atom is going away from you and squished to shorter wavelengths if it is coming toward you. This effect is called the Doppler shift. If planets are tugging a star back and forth in its own orbit, for example, astronomers can see the spectral lines shift from stretched to squished as the star moves relative to their telescopes.

Scientists also can use spectral lines to find complex molecules like the organic ones that glue us together and allow us to metabolize cheeseburgers. Nearby, within our own solar system, astronomers look for spectroscopic signatures in the light from comets, asteroids, planets, and moons. For distant objects, they must watch for molecules that emit photons of their own accord, because they are hot, for example. But for locations like Mars — where scientists have set down robots — the rovers can collect samples, and their instruments can heat the material, forcing the compounds to show their fingerprints whether they like it or not. Spectroscopy has allowed scientists to find out that organic molecules — even the amino acids that are the building blocks of DNA — and water are found throughout the solar system. New results suggest that the organic material in comets readily forms amino acids when the comets collide with planets or moons and heat up.

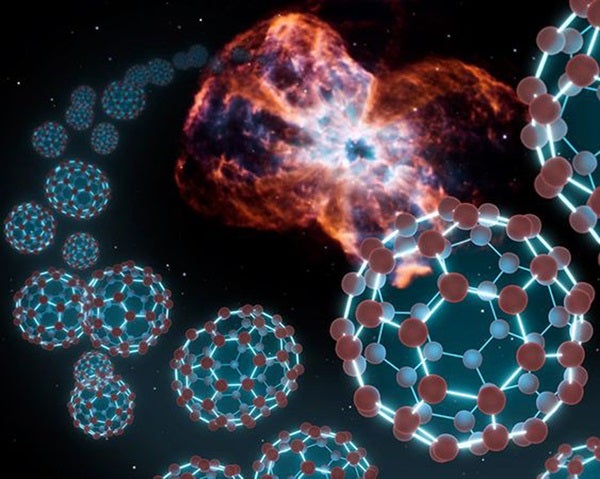

Venturing outside the confines of our hometown, astronomers still find plenty of chemical complexity. Interstellar space hosts such doozies as formic acid (which is what makes ant bites hurt), formaldehyde (which is used to preserve dead things), the kind of alcohol that is sold in bars, acetone (for removing interstellar nail polish), and the simplest form of sugar — glycoaldehyde. A molecule that contains 60 carbon atoms — named a buckyball and looking like a soccer ball — is even floating out there.

If anything is clear, it’s that the chemistry we see on Earth holds up in space. As astronomers investigate with ever-increasing spectroscopic sensitivity, they will be able to find out more about what molecules make up other solar systems. Already, they have found exoplanet atmospheres that contain carbon dioxide, oxygen, ozone, water, methane, and more. Some astronomers believe we could even detect extraterrestrial civilizations, at least ones that aren’t very “green,” by looking for synthetic molecules — like the chlorofluorocarbons in aerosols — in their atmospheres.

Expand your knowledge at Astronomy.com

Check out the complete Astronomy 101 series

Learn about our stellar neighborhood with the Tour the Solar System series

Read about the latest astronomy news