Once upon a time, our earliest ancestors, on the plains of Africa, gazed skyward and saw a bright Moon in our sky. Perhaps they wondered what it was and where it came from. The answers, however, took a very long time in coming.

The brightest object in the night sky, a target of fascination and folklore for eons, the Moon hides multiple mysteries. The name originated from the Old English mōna, whose basis predated 725 AD, and traces back more distantly to a proto-Germanic beginning. The Moon is always there, going through its orbit about Earth, and changing phase from our perspective night to night. For astronomy enthusiasts, it’s either the target of fascination, for lunar and planetary observers, or an object of scorn and derision, for deep-sky fans.

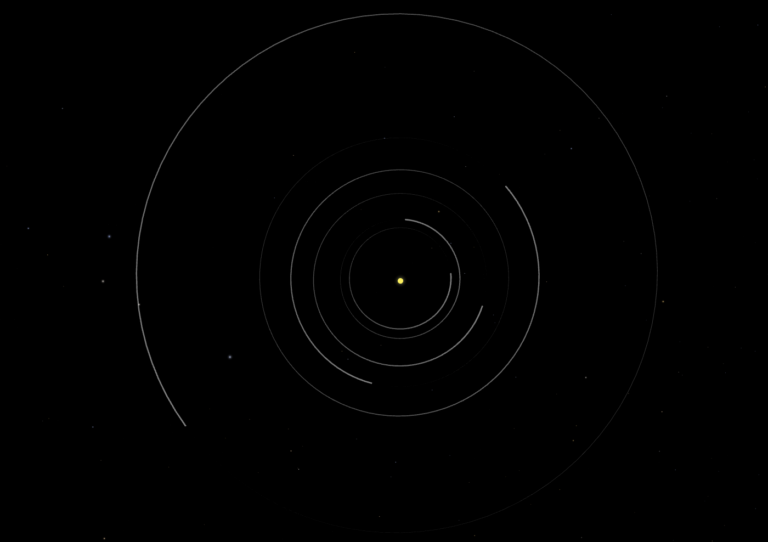

Puzzles over the Moon posed to planetary scientists go a long way back. One puzzle is the high angular momentum of the Earth-Moon system. That is, the high degrees of speed — rotational and orbital — and mass in the system. It’s also strange for a planet and moon system to be so relatively close in mass — the Moon’s roughly 1 percent of Earth’s mass is very high compared with most planetary systems. Moreover, the Moon has a weird orbit. It’s inclined 5.1° relative to the plane of the ecliptic, the orbital location of most bodies in the solar system. Lastly, the Moon is made of low-density stuff, only some 3.3 g/cm3, which is far less than Earth’s density or that of the other terrestrial planets.

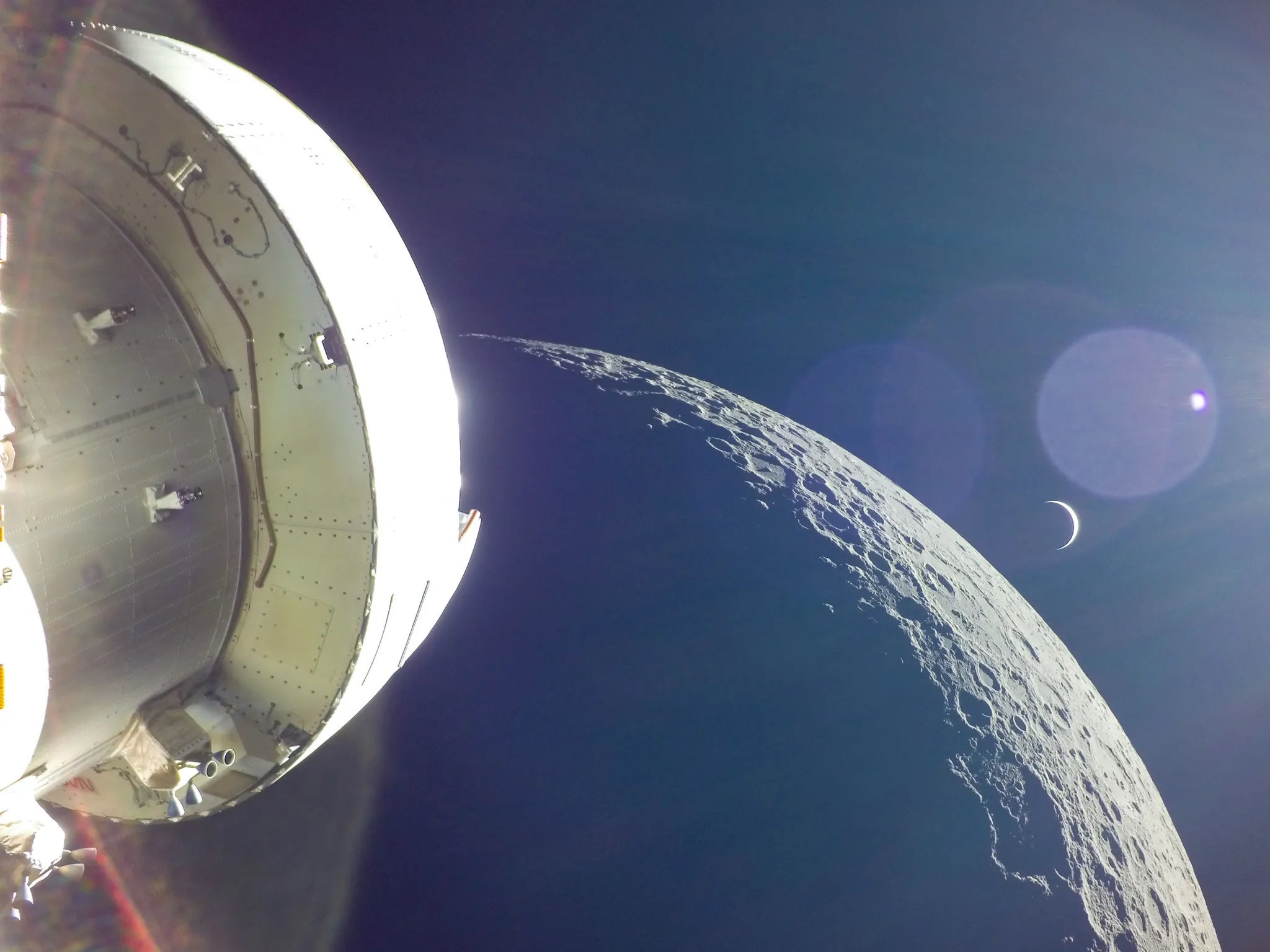

The Moon’s observational history didn’t push knowledge forward very quickly. For most of human history, people thought the Moon was a smooth, rocky body. That illusion was shattered in the fall of 1609 when Galileo, in his town of Padua, moved his newly invented telescope from the spires of a nearby church over to the Moon, making one of the first astronomical telescopic observations.

Mapping the Moon

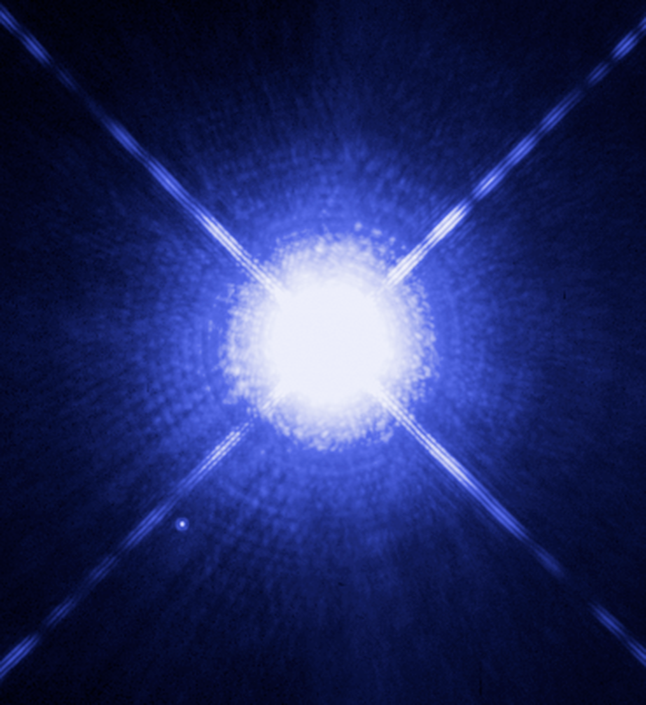

For centuries, astronomers armed with telescopes mapped the Moon, carefully placing craters and other features. But the question of lunar origin still stood right where it always had. Slowly, it dawned on planetary scientists that several leading possibilities existed. Into the 20th Century, they determined that most lunar features were impact related rather than volcanic. Perhaps the Moon was captured by Earth. Maybe Earth and the Moon formed simultaneously as a so-called double planet. Earth may have experienced a fission episode in which it gave birth to the Moon during rapid rotation. Small bodies like planetesimals in the early solar system might have accumulated in the area of Earth, creating the Moon. Or perhaps a large impact of some type was involved.

After a very long wait, scientists began to accumulate hard evidence for lunar origins by the time of the Apollo missions, when large numbers of Moon rocks were returned to Earth. Between 1969 and 1972 astronauts brought back 2,415 Moon rocks amounting to 842 pounds (342 kg) of samples. From 1970 through 1976, Soviet Luna missions added to the total, returning 0.7 pounds (0.32 kg) more. And adding to that is a cache of 584 named lunar meteorites that have fallen to Earth and been recovered and identified as pieces of the Moon. (One proud object in my collection is a slice of Dar al Gani 400, a 1.4 kg stone found in Libya in 1998.)

A revolution in thinking commenced in 1975, following the initial studies of Moon rocks. At the University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Lab, two scientists, Bill Hartmann and Don Davis, produced an influential paper. They proposed a giant impact, one from a body they called Theia (for the Greek mythological mother of the Moon goddess Selene), took place, knocking a vast amount of debris from early Earth, which accreted into a ring and then into the Moon. They focused on this event happening some 4.5 billion years ago.

Related: The Full Moon calendar for 2023 and 2024

The Giant Impact Hypothesis

At first the idea failed to catch on. But momentum for what came to be called the Giant Impact Hypothesis eventually took hold. In the 1980s influential science conferences featured fresh evidence and debates that added to its luster. Computer models added a great deal of credence to the idea, and it was accelerated in the 1990s by a young planetary scientist named Robin Canup, who added vital details in a series of important papers.

To this date, the impact scenario is by far the strongest idea for the Moon’s origin, and explains many things, including the virtually identical nature of oxygen isotopes found in Earth rocks and Moon rocks, which suggest a common origin.

We still don’t know for sure. But it seems that the Moon in our sky formed from a long-ago, and extraordinary large, big splat. And what of Theia? Much of it was absorbed into Earth. You’re most likely standing on it.

David J. Eicher is Editor of Astronomy, author of 26 books on science and history, and a board member of the Starmus Festival and of Lowell Observatory.