Key Takeaways:

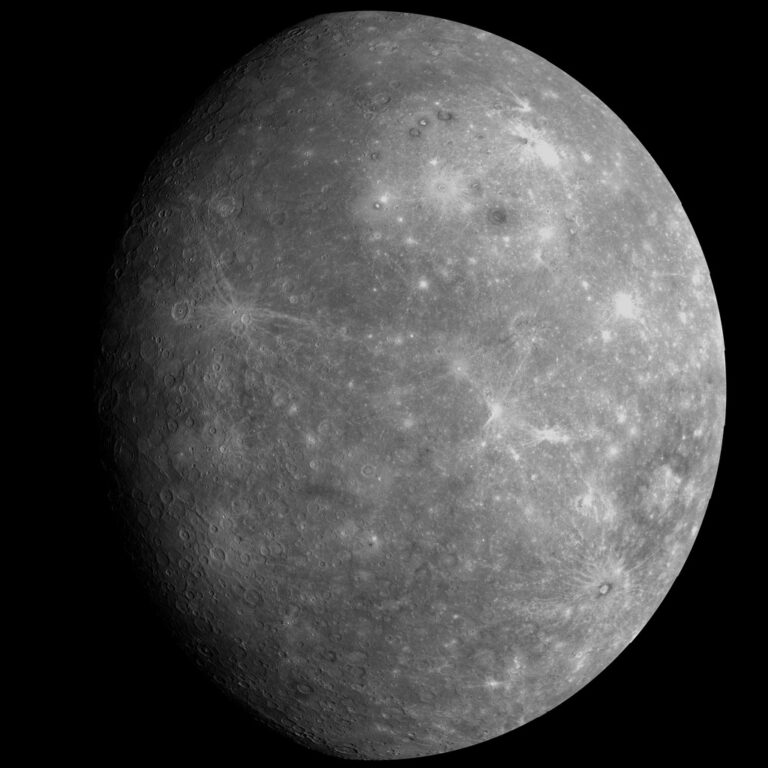

- Voyager 1, launched in 1977, exceeded 16 billion miles, prioritizing a Jupiter and Saturn flyby due to a rare planetary alignment and budgetary constraints.

- The mission's trajectory, optimized for a close Titan encounter at Saturn, precluded a Pluto flyby, a decision influenced by the anticipated launch of a future Pluto-focused mission.

- Limited knowledge of Pluto's characteristics (size, atmosphere, moons) in the 1970s, coupled with the absence of the Hubble Space Telescope and the unknown existence of the Kuiper Belt, would have hampered a 1986 Voyager 1 Pluto encounter.

- The Voyager 1's focus on Saturn, particularly Titan, was deemed scientifically more valuable at the time than a Pluto flyby, a decision ultimately supporting the later New Horizons mission.

Voyager 1 has now traveled more than 16 billion miles (26 billion kilometers), drifting past Jupiter and Saturn on a long haul out of the solar system. And its incredible success helped pave the way for both the Galileo and Cassini spacecraft that followed in its footsteps.

Yet when NASA initially programmed what became the first “interstellar mission,” Voyager was actually set to see Pluto in March of 1986 as well. The plan changed mid-flight.

But why? That question raises a fun series of “what ifs.”

NASA built the twin Voyager spacecraft to take advantage of a rare planetary alignment that put Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune within reach at once. Such a window only comes every 175 years.

However, sending a single spacecraft was too expensive with all the orbital complexities. NASA decided to launch Voyager 1 on a route that would primarily take it past Jupiter and Saturn while Voyager 2 could do the same before winding past Uranus and Neptune.

When the pair launched from Cape Canaveral in 1977, astronomers knew little about the outer solar system. The Pioneer spacecraft had already extended humanity’s reach to the gaseous giants, but it carried rudimentary instrumentation.

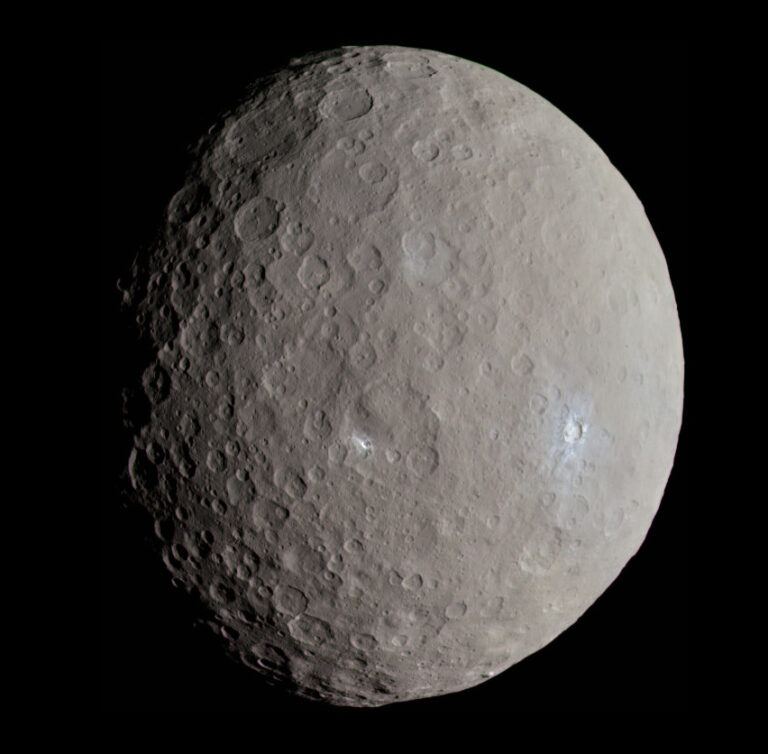

Even less was known about far-off Pluto. Astronomers had recently detected methane on the dwarf planet, but the planet’s atmosphere was unknown. Scientists had only speculated about the existence of the Kuiper Belt.

“We didn’t even know Pluto’s size,” New Horizons Principal Investigator Alan Stern said in a recent interview. “All we knew was that Pluto had a moon.”

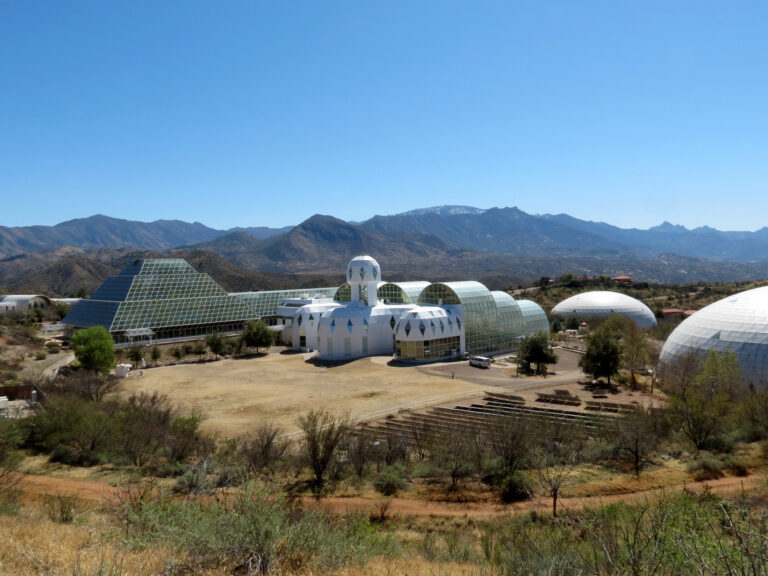

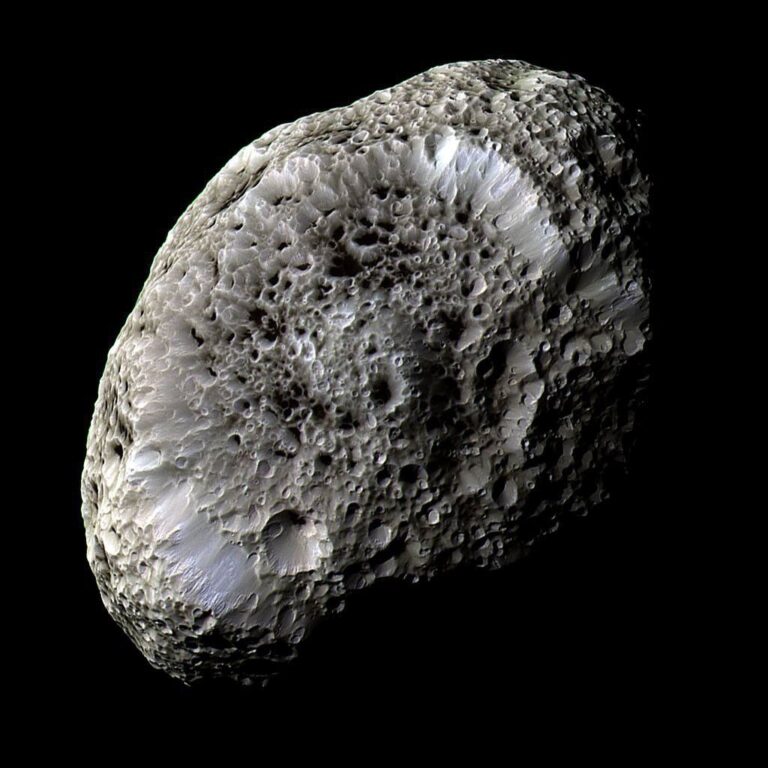

Instead, Saturn’s planet-like moon Titan was the darling of planetary sciences in the 1970s, and it enamored astronomers with a thick atmosphere and potential warmth.

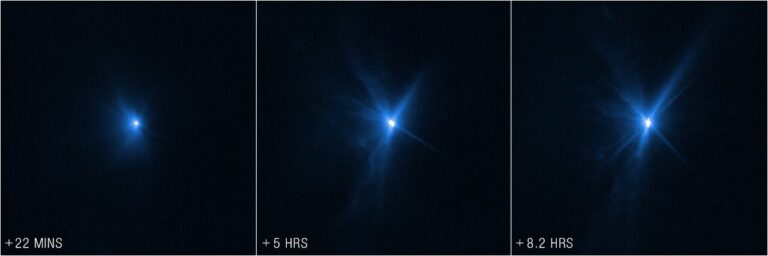

Astronomers decided that in order to optimize their science at Saturn, they’d need an orbit that brought Voyager 1 up close with Titan. But that flyby also would put Pluto out of reach after the spacecraft lifted out of our solar system’s ecliptic plane.

“It was a pretty straightforward decision for them because they thought there was going to be a third Voyager mission that could come along and go to Pluto,” Stern says.

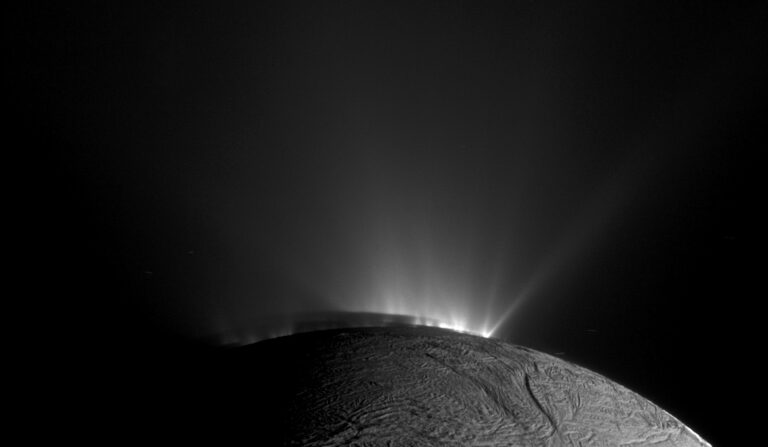

Interestingly, Voyager 2, whose trajectory couldn’t have realistically reached Pluto, played a part in making the case for a Pluto flyby. The final Voyager program flyby revealed Neptune’s moon Triton in 1989. It was the last time humans saw a new world for the first time. Voyager 2 found an icy and dynamic moon complete with ice volcanoes. Surface features, as well as Triton’s strange orbit, make astronomers suspect it’s actually a kidnapped Pluto.

The moon is still seen as the closest stand-in we have for a world that New Horizons will finally reveal next month.

In a fascinating post last year, Stern pondered what Voyager would have seen if it had visited Pluto. He says that because astronomers didn’t know about the dwarf planet’s atmosphere, they would not have been prepared for what they saw. The Hubble Space Telescope also didn’t exist yet, so Pluto’s many small moons were unknown. And because the Kuiper Belt wasn’t known to exist yet either, Voyager couldn’t have been programmed to continue on to additional worlds like New Horizons.

“I’m very glad that they chose not to go to Pluto in 1986,” Stern says. “We’ll do a better job at Pluto with modern instruments than they would have, and they did a much better job at Saturn by not going to Pluto — they got to explore Titan up close. For our team, it also worked out very well because there would have been no need to do New Horizons.”

Eric Betz is an associate editor of Astronomy. He’s on Twitter: @ericbetz.