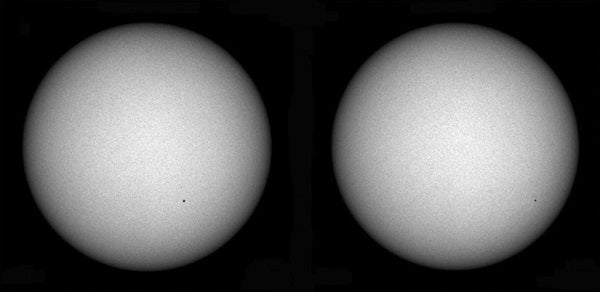

But at the beginning of a new cycle, the first spots to appear are generally too small to be detected without optical aid. Using safe solar filters in front of binoculars will help bring some of these devilishly delightful spots into view. Unfortunately, the task is not easy.

Cycle 25 brewing?

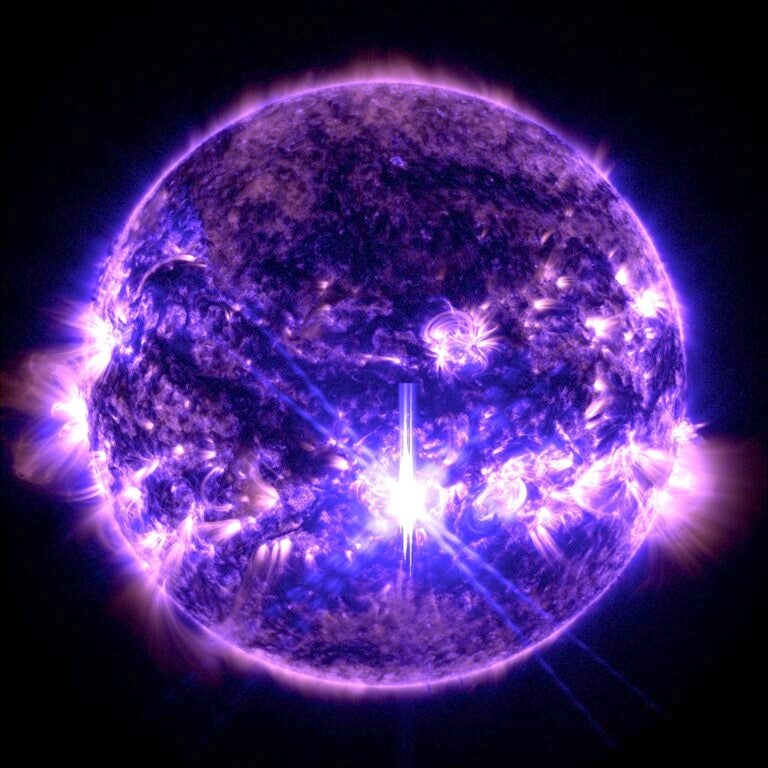

In their February 2020 article in Research Notes of the American Astronomical Society, Dibyendu Nandy from the Center of Excellence in Space Sciences India and his colleagues argue that solar cycle 25 may be dawning. No one knows exactly how a new solar cycle starts, but it’s thought to be based in a complex interaction of ionized gas and the Sun’s magnetic field. We do know that spots in a new cycle will have their magnetic poles reversed from those in the last cycle — in this case, cycle 24, which ended around December 2019.

Since November 2019, solar astronomers have been observing new sunspots with reversed polarity around 25˚ north and south latitudes. And this happens to be exactly where they expected new spots from solar cycle 25 to appear. Seeing such spots is a positive sign that a new solar cycle is in the making.

The binocular challenge

Before we get into viewing cycle 25 sunspots, two definitions. A sunspot’s umbra is the dark inner part. Its penumbra is the lighter outer region. Currently, the stammering start of cycle 25 has been creating three types of spots: Short-lived naked cores, which are state-sized dark spots without any penumbra; partially dressed proto-sunspots, which are Moon-sized marks with only a partial penumbra that doesn’t completely surround the core; and fully dressed sunspots, which are Earth-sized and feature a dark core, an umbra, and a penumbra.

I began systematically observing the Sun on June 10, 2020. That day, I used handheld 8×42 binoculars to see without difficulty a fully dressed Earth-sized sunspot labeled AR 2765. (AR stands for active region.) The evolved spot was in the Sun’s southern hemisphere and had already sailed past the central meridian.

Two days later, the foreshortened spot appeared both smaller and less apparent, making it more difficult to detect. Only when I braced the binoculars against a wooden post could I resolve the spot, which looked more smoky gray than black.

A similar situation occurred July 25, when another Earth-sized sunspot (AR 2767) appeared in the Sun’s southern hemisphere. As for AR 2765, handheld 8×42 binoculars easily brought it into view. It remained visible until July 31, when the spot’s highly foreshortened umbra diminished in apparent size enough that it became a challenge to see through the binoculars. It vanished from view the next day.

By August 5, a more challenging spot (AR 2770) in the Sun’s northern hemisphere had slid into binocular view. That day, the foreshortened spot was difficult to see even with braced 10×50 binoculars. I had to know exactly where to look to pick it out. Sighting AR 2770 was similar to spotting Venus in the daytime — if you look away for an instant, it’s gone.

Two days later, however, the Earth-sized spot was a cinch through handheld binoculars. I finally lost sight of it on August 11, the day after an enigmatic light bridge had split the spot in two, and before it had dwindled into a naked pore.

Observe in sunlight

By the time you read this, other Earth-sized spots may be moving across the Sun. Each offers you a chance to test your direct vision through filtered binoculars. I want to learn how small of a sunspot you can see, especially if you use tripod-mounted binoculars or those larger than 10×50. Good luck, and, as always, send what you see and don’t see to sjomeara31@gmail.com.